Every Saturday and Sunday you will find dozens of families lined up on grass fields, cheering for kids in brightly colored jerseys. No matter the sport, off in a shaded corner of the sports complex, you will see a lone parent surrounded by others begging for answers. One by one they lift up shirts, raise pantlegs, and stick out their tongues, all hoping to get a quick curbside diagnosis of what ails them (or their kid). After all, it’s not serious enough to make an appointment, but annoying enough to seize the opportunity to consult that medical professional—even if it’s at a 6U soccer game.

My old college strength coach would yell at my teammates who were struggling to complete a basic power clean: “DO LESS.” You heard it here. Doing less is sometimes better than doing more, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XIf you’ve been writing workouts as long as I have, you’ll realize that your desired expertise is quite parallel to that of the doctor. No, I don’t mean that you will be respected and honored, but rather, people will conveniently come to you with their fitness infirmaries. The strength and conditioning parallel occurs when a former friend asks for workouts, a local coach sends you their “program” asking for pointers and corrections—or, my favorite, an incoming college freshman shows you their Teambuildr workout and asks what a “seal-krock-IR-Row-Press” is and how are they supposed to do that to max for 15 reps?

When you become the beacon of exercise knowledge to many, you find yourself diagnosing diseased workouts when you should be relaxing and enjoying a ballgame.

Checking Your Trumpet Oil

In a world where so much training knowledge is at your fingertips (i.e., right here), we have to wonder why things are getting so blurry when our vision should be 20/20. The phrase that comes to mind is one that my old college strength coach would yell at my teammates who were struggling to complete a basic power clean: “DO LESS.” Yes, you heard it here, doing less is sometimes better than doing more. But the thought of doing less while trying to accomplish something difficult is a bit confusing. Power cleans, for example, require many consecutive and coordinated events to achieve a successful lift. We don’t want to miss any steps that could result in a failed rep—but, therein lies the problem.

We sometimes overemphasize the wrong thing and miss a much more important step. Therefore, doing less can help you maximize what really gets the job done. Less fluff, if you will.

In 2019, I won a local business award and at the ceremony, an unassuming guest speaker took the stage—there was nothing about him that looked impressive. From his shoes, to his tie, and even his haircut, he just looked like the kind of person you’d give a head nod too while standing in line at the bank. And yet, on the projector behind him were a pair of numbers: 293 and 216. Under his leadership, his company had grown 293% in three years and made $216 million dollars that year alone.

We’ve learned that using a weighted bat prior to stepping in the box SIGNIFICANTLY reduces swing velocity and accuracy. Batters reported that it felt better, but the weights did not improve performance, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XThose stats hooked my attention and I listened to what this Average-Joe-Business-Genius had to say. After all of these years, I still remember the phrase “trumpet oil.” He told us a story of a giant musical instrument company that had fallen on hard times and needed more cash flow. They had decided that since every trumpet needed trumpet oil, they would save the ship by selling an essential product. After a year, sales results were looking even worse than before. The problem wasn’t that they couldn’t sell trumpet oil—after all, they sold one with almost every instrument—it was that the profit margin on the oil was less than a dollar, whereas a high level trumpet could bring in thousands. Luckily, the speaker said, they began diversifying the kind of trumpets they offered and the company survived to tell their tale.

Periodically, I ask myself: what is the trumpet oil of my business or training? I always think it will be obvious, but it turns out I have to dig deeper and ask myself a series of questions before the light bulb goes off. As a coach, you might have limited resources or time with your athletes, and wasting any of it can hold you and your team back.

So, grab your stethoscope—or clipboard—and join me as we diagnose what is keeping your program from achieving the results you want in the time that you have.

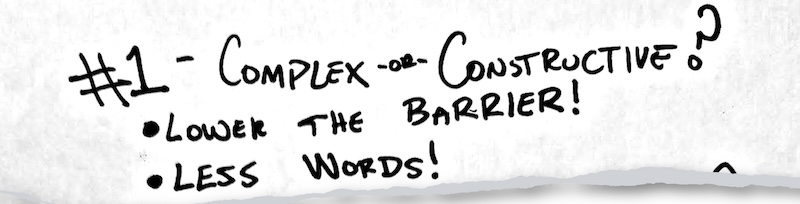

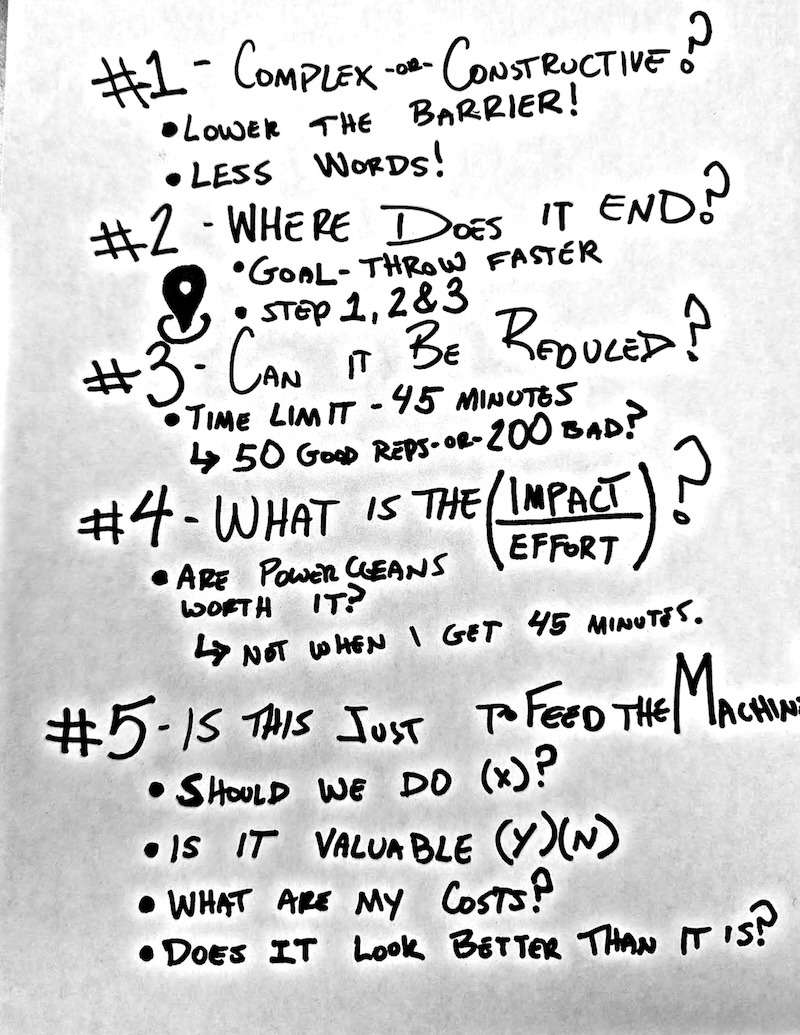

#1. Is It Complex or Constructive?

Creativity can be a weapon for strength coaches to push and advance the field; however, just as some modern art pieces look like a toddler splattered paint on a canvas, so can our exercise inclusions. Too often I will see a video on social media of a coach showing a complex, 11-step drill to teach a young athlete how to “learn” a skill better.

Creativity can be a weapon for strength coaches to push and advance the field; however, just as some modern art pieces look like a toddler splattered paint on a canvas, so can our exercise inclusions, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XIf you know Westside Barbell, you probably also know of the late great Louie Simmons, who revolutionized the art of powerlifting through creativity and invention. However, a video of him in 2013 coaching Olympic lifters created some controversy and got some laughs. In the video he had attached bands to a bar (as usual) and had his lifters perform their very technical lifts with the bands pulling them every which way.

The problem was not the accommodating resistance, but rather the lifters struggling to maintain their bar path with bands creating non-traditional vectors of “pull.” In the video, many of the lifters politely did as he said while smirking at the drills. In a similar fashion, I have seen videos of kids practicing their jump shots with bands attached to their wrists, ankles, knees, and elbows. The issue in these situations is that the athletes are unable to perform their normal skill patterns due to the “awkward” resistance and therefore could be building worse skill.

A classic medical line when treating a patient is “DO NO HARM,” but like Dr. Frankenstein, we are tempted to stitch things together in the hopes of creating something amazing—but it often turns out to be a monster. A great example of removing complexity is found in Major League Baseball. Comparing the early 2000s to today’s game, there are two major differences: smaller biceps and almost nobody warms up with a weighted bat. The reason is that we’ve learned that using a weighted bat prior to stepping in the box SIGNIFICANTLY reduces swing velocity and accuracy. Although batters reported that it felt better, the complexity of the weights did not improve the athletes’ performance.1

What some coaches do not realize is that even our WORDS can complicate what an athlete is trying to achieve in the weight room. If we encourage our athletes by saying too many cues or even if we cue the wrong thing, we can reduce their skill and performance. Researchers are showing that by cueing internally (flex harder) rather than externally (push harder) reduces neuromuscular performance!2 In many cases, the more we say in the heat of battle, the more complicated we can make it, and the less constructive it winds up being.

While developing a program or making a business decision, I always try and make sure that I’m not adding steps to achieve the exact same goal—or worse, take away from the desired outcome.

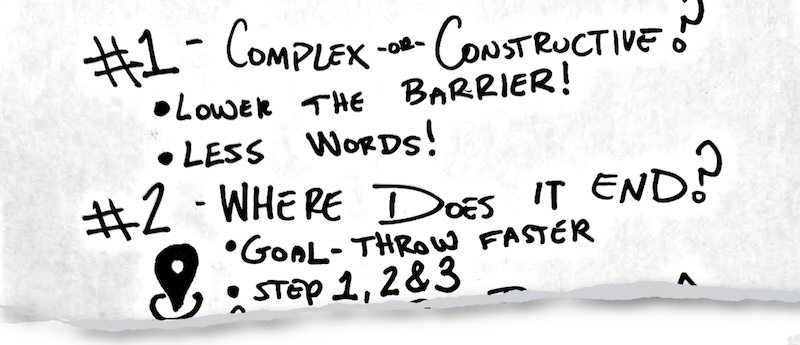

#2. Where Does It End?

Whenever you open Maps on your phone, it will sync to your current location and ask for your destination—the system cannot pick the best path without knowing exactly where you want to go. Many times, as strength coaches, we do the same for a program’s desired goals—bigger, faster, stronger, healthier, etc, etc. But then we implement exercises and drills with an open-ended philosophy of let’s see where this goes.

As athletes become masters of simpler movements, we might be tempted to add unnecessary steps that burn more calories but don’t build better athletes, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XIf I don’t know the peak or end of an exercise’s progression, I can fall victim to the faults of Question #1. As athletes become masters of simpler movements, we might be tempted to add unnecessary steps that burn more calories but don’t build better athletes. For example, if I have 24 weeks of medball throw progressions, I make sure that each step builds the next one up in some way as we work towards the more challenging movement in the end.

If I simply started with an ambiguous throw and then changed it based on my whim, I could find myself in a never-ending storm of guesswork. I’ve found it’s always best to know my destination before I plan the trip, and my goal is the fastest and safest route. I know this can be hard for many coaches, because the temptation to find unique and new exercises is high—especially with so many people putting out such good content on social media.

When they learn about disease diagnoses in medical school, there is a phrase taught to practitioners: “when you hear hoof beats, think horse not zebra.” This is because it is tempting to see a common side effect and think of a less common disease! If you choose zebra as your destination, you might create a lot of work for the wrong answer. So, I’ve taken the philosophy of simplification—I am looking for horses and setting my maps to that destination. I am not saying you shouldn’t have flexibility within your plan; after all, I utilize autoregulation in all my training. But I am saying you should have an idea of where everything you choose will end up.

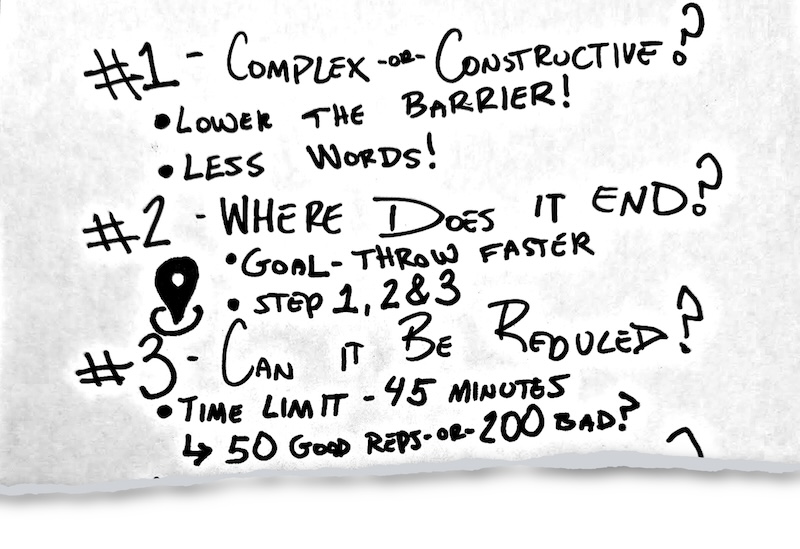

#3. Can It Be Reduced?

There is a product that every single American uses that costs us over twice as much as it should—yet, we pay the price hike without a second thought. Every week, when you do a load of laundry and you pour a capful of liquid detergent over your clothes, you could be spending FIVE TIMES as much as you would if you simply got a concentrated powder form. You can go online right now and get 9 kilograms of detergent powder for roughly the same price as a half-gallon of the liquid. This is because the transportation and plastic use of the diluted product costs more, and that cost is passed on to us, the consumers.

Unfortunately, as a society, we have become accustomed to liquid detergent and yes, sigh, even I still use the more expensive form. In the field of medicine, doctors work hard at concentrating certain drugs so that they can be better absorbed at the site of administration. Sometimes, in training and business, we keep a diluted product around because it is what we are used to. But massive change can be had if we figure out how to reduce it to its most crucial components.

By doing less in the weight room, we can see progress with better recovery, get higher-quality reps from reduced fatigue, and find more time for coaching, says @endunamoo_sc. Share on XA great example is what we do in the weight room. I have had many high school and college athletes come and tell me about their workouts and how they couldn’t even get half of it done in their time window. Some of these workouts prescribed four sets of eight reps for 10 different exercises, all of which had high intensity percentages. Those poor kids don’t stand a chance. Some of them could barely complete their primary lift of the day.

My question is whether that much work is needed to yield a positive result. For years, my athletes and I have seen fantastic results with as few as three total sets of an exercise, including warm ups. Some research shows that even with one-third the volume as other groups, similar strength gains are found.3,4 Even with more complex lifts, such as cleans and snatches, training with a moderate amount of volume seems to produce better results when compared to nearly double the workload, according to a growing amount of research.5

The same is true when running a business—it might be nice to have a receptionist, a shake maker, and a cleaning person. But when all three of them have hours of down time each day, it might be smart to reduce your staff and hand out more responsibilities. I learned a long time ago that none of these reductions should be looked at as a bad thing. By doing less in the weight room, we can see progress with better recovery, get higher-quality reps from reduced fatigue, and find more time for coaching. In business, if I have fewer employees, I can pay each person more while still saving money from the reduction. In most instances, we can concentrate our efforts to produce better results with less waste.

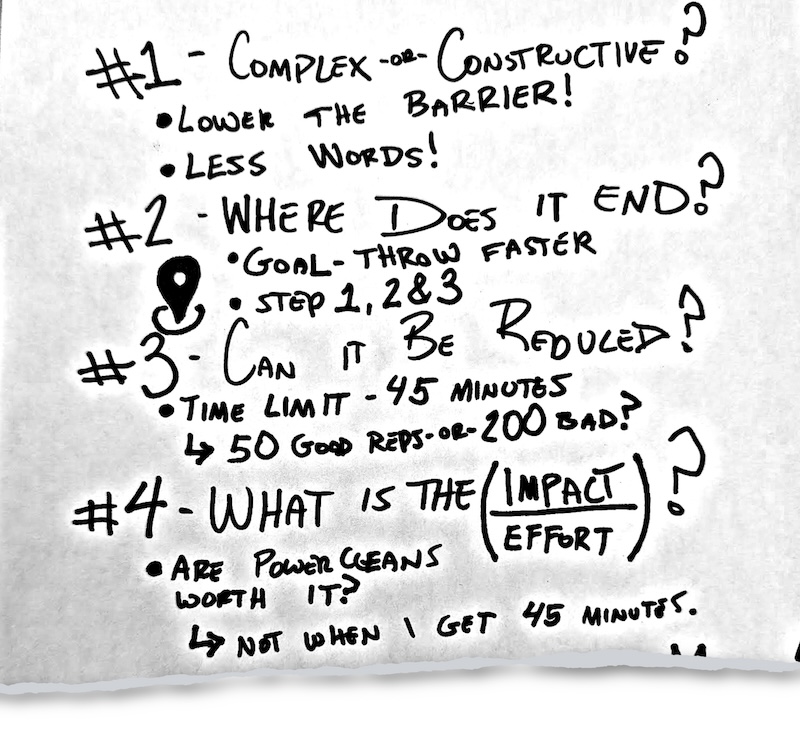

#4. What Is the Impact-to-Effort Ratio?

Every year, almost 66,000 Americans flip open their laptops and attempt to become day traders. For those who might not know, day trading involves buying and selling securities on the same day, often online, based on small, short-term price fluctuations. The promise of becoming rich in a single day by mastering the fluctuations of the market is so promising that many quit their jobs to give it a try.

Unfortunately, research shows that only 3% of traders have made any of their money back in two years, with less than 1% making enough to live on. From the outside, it looks like day traders are putting in countless hours of hard work, but according to the statistics, they’re basically playing the lottery—just with a lot more effort.6

There are many instances where coaches implement difficult and technical training modalities that simply add a whole lot of sweat for a small amount of success. Depending on who you talk to, some coaches believe that Olympic weightlifting is one of the biggest wastes of time for athletes. Rather than spend countless hours mastering the second pull, some would rather perform similar power exercises with lower barriers to entry. I’m not going to say the juice isn’t worth the squeeze, but there might be situations where doing less means getting more in the time frame you have. When I coached in college, we’d be lucky to have the men’s basketball team show up to one weight room day a week. We could have spent that precious time teaching them how to catch a power clean in the perfect front rack position; or we could have spent that time getting better results with simpler tools.

The same is true in business. We’ve all been to restaurants that seem to have an endless number of options on their menu, and let’s be honest, none of them are that great. Behind the scenes, that eatery is creating larger costs to purchase, store, and possibly throw away the large diversity in food items. That is why some stores like Chic-fil-A sell 25% the number of products as compared to their peers, usually only offering a whopping 12 items. By cutting out waste, they actually have one of the highest profit margins of all fast-food chains. When I audit my business or training, I’m looking at things that cost a lot of time and energy without bringing in the bucks.

#5. Is This Just to Feed the Machine?

My facility has expanded three times over its lifespan, from 800 to 5,000 to its current 12,000 square feet. Each of these growth phases were essential in seeing more athletes and doing safer, higher-quality work.

While at my second location, I began working with an old cowboy whose back could not handle the rodeo scene like it used to: in his words, he was “one bad weekend away from having surgery and hanging up his spurs.” Luckily for him, a friend at his old gym told him about how we helped his son return to play after getting hurt at school. He gave me a call and we got him back on the horse, literally. A year later, he VOLUNTEERED to be my general contractor for my third facility, saving me some major headaches and finances.

I tell this story because not only was he a hard working “son of a gun,” he was also a great business man. One of the best pieces of advice he ever gave me was “are you feeding your family or are you feeding the machine.” In his roofing and contracting years, he took his business from a two-man situation to a giant, multi-million-dollar-a-year business with dozens of employees. From the outside looking in, you would assume he was killing it doing giant million-dollar projects with a fleet of trucks and workers. However, he let me know that with larger projects comes more expensive insurance, bonds that must be won, and payroll that can sink a ship if you have a lull in work. At the end of the day, he was bringing home the same amount of profit with 50 employees as he was with five, he just had a lot more headaches during tax season.

As a business owner, I am always tempted to expand and take on a new project—for example, pickle ball. With the rapid growth in popularity, everyone and their dog has advised me to get in the game. Unfortunately, to do this, I would need to spend nearly six figures to get courts, cover, equipment, AC, check-in systems, bathrooms, and you name it. Not to mention the additional employee costs. If I take out a loan, I might see a profit of 1-3% every year—or, worse, a loss. All of that money, mental effort, and sweat would mostly go to feeding the machine.

In training, I find myself being tempted to do the same thing. Whether it is a new gadget, complex training strategy, or time-consuming drill, I have to remind myself that we might do all of this work just to feed the machine and not reap much reward. As a coach at a school, your AD might want to see non-stop action and exhausted kids, but you have to ask—“does this feed the machine (ego) or feed my family (team).”

Bigger is not always better.

Performing Your Own Audit

A good five-step audit normally helps me refocus and realize what needs to happen in my business and my training. Like a doctor running a battery of tests, you can find that some symptoms are not what you thought—and treating them with the wrong medicine will not do much good. Unlike the 2004-2012 TV series House, your mistakes will not be as complicated as the diseases he treated—but it is important to take a good look at the rash… I mean your program… and try to treat it before a bigger problem arises.

In many instances, I have been able to course correct with only one of these questions, but there have been times that after asking all five I still have to scratch my head to find the issue. So, whether you’re the doctor at the sports field getting asked to check out everyone’s minor maladies, or you’re the coach who falls into the trap of prescribing seal-krock-IR-Row-Presses for a 15-rep max, the situation can always be treated with a quick five question diagnosis.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Montoya BS, Brown LE, Coburn JW, Zinder SM. Effect of warm-up with different weighted bats on normal baseball bat velocity. J Strength Cond Res. 2009 Aug;23(5):1566-9. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181a3929e. PMID: 19593220. Otsuji T, Abe M, Kinoshita H. After-effects of using a weighted bat on subsequent swing velocity and batters’ perceptions of swing velocity and heaviness. Percept Mot Skills. 2002 Feb;94(1):119-26. doi: 10.2466/pms.2002.94.1.119. PMID: 11883550.

2. Lohse KR, Sherwood DE. Thinking about muscles: the neuromuscular effects of attentional focus on accuracy and fatigue. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2012 Jul;140(3):236-45. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.05.009. Epub 2012 Jun 7. PMID: 22683497.

3. Ostrowski K, Wilson GJ, Weatherby R, Murphy PW, Little AD. The effect of weight training volume on hormonal output and muscular size and function. J Strength Cond Res. 1997;11:149–54.)

4. Schoenfeld BJ, Contreras B, Krieger J, Grgic J, Delcastillo K, Belliard R, Alto A. Resistance Training Volume Enhances Muscle Hypertrophy but Not Strength in Trained Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019 Jan;51(1):94-103. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001764. PMID: 30153194; PMCID: PMC6303131.)

5. González-Badillo JJ, Gorostiaga EM, Arellano R, Izquierdo M. Moderate resistance training volume produces more favorable strength gains than high or low volumes during a short-term training cycle. J Strength Cond Res. 2005 Aug;19(3):689-97. doi: 10.1519/R-15574.1. PMID: 16095427.)

6. What’sthebigdata.com. What Percentage of Day Traders Make Money – Statistics 2024.