All athletes want to achieve peak performance at the right time, which requires a careful balance of training, nutrition, recovery, and rest. For many reasons, what works as the best training program for one runner may be the opposite for someone else. Oxidative stress is one of these reasons.

Oxidative stress is unavoidable in daily life, but professional athletes must contend with exposure from the very things they do the most—train and compete. Reasonable levels of oxidative stress can enhance sprint performance. However, it’s a slippery slope: too much, and you’ll find your performance and energy levels dropping.

Oxidative stress can be damaging, but it also signals the body to adapt, get fitter, and boost its intrinsic antioxidant defenses. The fitter an athlete becomes, the more adept their body’s antioxidant response gets. Share on XWithout adequate intervention, oxidative stress can impact sprint performance and beyond. It can also affect an athlete’s health and longevity.

What Is Oxidative Stress?

Oxidative stress is an imbalance of antioxidants and free radicals in the body—specifically, more free radicals than antioxidants. Antioxidants are compounds that neutralize free radicals in the body. They reduce the effects of oxidative stress.

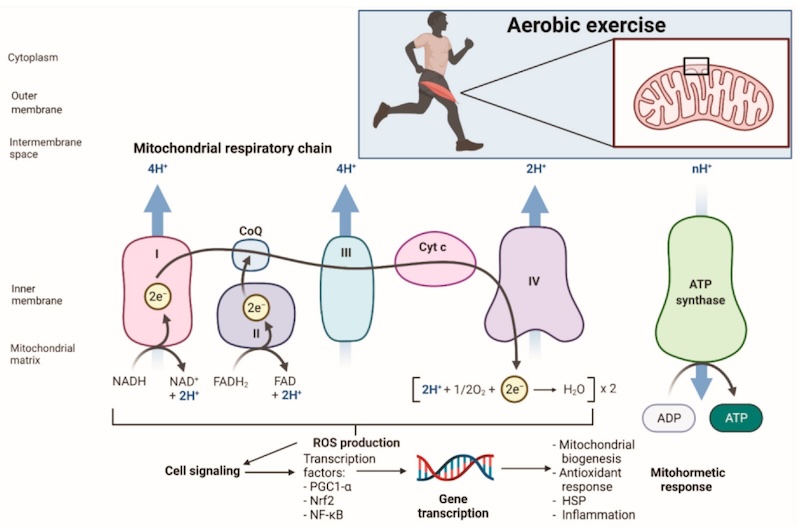

Cells continuously produce free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) as part of metabolic processes. ROS production during physical activity significantly impacts sports performance. During exercise, the metabolism speeds up to meet the body’s increased need for oxygen, which triggers the release of ROS. Physical activity also triggers enzyme activation, which increases the number of ROS. Over time, this process can harm cells and contribute to muscle damage and fatigue. While oxidative stress can positively impact performance in moderation, it’s also linked to many diseases, including diabetes, Parkinson’s, cancer, and heart disease.

However, physical activity can also increase antioxidants, making the big picture significantly more complex. Oxidative stress can be damaging, but it also signals the body to adapt, get fitter, and boost its intrinsic antioxidant defenses. The fitter an athlete becomes, the more adept their body’s antioxidant response gets. Since antioxidants combat free radicals in the body, many athletes take supplements to prevent oxidative stress. However, too much blocks some of the natural training gains associated with it. The trick is to find the right balance.

What Causes Oxidative Stress?

The presence of ROS increases due to physical and environmental stressors. Exercise is one of these stressors, as is any situation where oxygen consumption is increased. Professional athletes train and perform at levels where maximum oxygen is required, so ROS production is that much higher.

Without adequate intervention, oxidative stress can impact sprint performance and beyond. It can also affect an athlete's health and longevity, says Jack Shaw. Share on XIn addition to exercise, oxidative stress can also be caused by pollution, sun exposure, and stress. Any of these triggers can be present in the athlete’s environment. You may not be aware that you’re experiencing oxidative stress, as no standout symptoms exist until the condition is relatively advanced.

Weighing the Benefits of Oxidative Stress for Athletes

Although oxidative stress must be carefully managed, athletes can benefit from the levels of oxidative stress associated with low to moderate levels of exercise. This means keeping your heart rate at about 65% to 85% of your max heart rate. Low to moderate levels of exercise can stimulate adaptive responses in the body, improving resilience and performance without damaging tissue and organs.

Oxidative stress can also activate signaling pathways that promote hypertrophy and strength gains. This additional power is crucial in a world where force applied to the ground is a key differentiator between elite and sub-elite sprinters. Moderate oxidative stress can also stimulate the production of new mitochondria in a process called mitochondrial biogenesis, enhancing aerobic capacity and endurance performance.

Image 1. Source: “Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Function and Adaptation to Exercise: New Perspectives in Nutrition.” Creative Commons License here.

ROS can promote vasodilation, or a widening of the blood vessels, which increases blood flow to muscles during exercise. The better the blood circulates, the more effective the body’s nutrient and waste removal systems work. Acute oxidative stress also initiates an inflammatory response when chronic inflammation reaches harmful levels—essential for muscle repair and adaptation during exercise.

The presence of oxidative stress signals the body to adapt to the demands of training, which can improve metabolic efficiency and overall athletic performance.

Understanding the Drawbacks of Oxidative Stress

Despite these benefits, oxidative stress can be an unwieldy force. High levels of ROS can cause oxidative damage to muscle fibers during training. This damage is a significant factor in the development of delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), which can impair muscle function in the short term. While the inflammatory responses that oxidative stress triggers are necessary for muscle repair, they can also lead to prolonged soreness and recovery time, which is challenging for athletes in intense training.

Understanding the balance between harmful and beneficial effects of oxidative stress can help athletes and coaches optimize training strategies for better performance and recovery. Share on XOxidative stress is also associated with a quicker onset of fatigue during exercise. ROS can impair energy production processes in muscle cells, and excessive amounts can decrease performance. Chronic oxidative stress can lead to overtraining syndrome, which means you’ll take longer to recover from workouts and experience prolonged fatigue.

Other issues with oxidative stress are weakened muscle and connective tissues, which increase the likelihood of injuries. There is also evidence that oxidative stress can affect cognitive function, which can impact decision-making during competition.

Understanding the balance between harmful and beneficial effects of oxidative stress can help athletes and coaches optimize training strategies for better performance and recovery.

How Oxidative Stress Affects a Runner’s Short- and Long-Term Performance

Excess oxidative stress can begin impacting sprinting performance relatively early. Many believe that the most intensive training on the track is anything that results in high levels of lactic acid. Oxidative stress exacerbates the inflammation associated with intensive training. High levels of ROS can also increase the perception of fatigue, potentially making the effects of lactic acid more pronounced.

Every athlete is different—some may experience more overt symptoms, particularly fatigue and slow recovery, than others in the short term. In the long term, the effects become more apparent. If performance is decreasing and injuries are becoming more prevalent, explore solutions to this issue before it has lasting consequences.

Chronic oxidative stress can weaken the immune system, making you more prone to illness and infection. Over time, these issues significantly impact performance and training. It also contributes to accelerated cellular aging and increases the risk of chronic diseases. When dealing with the effects of oxidative stress, you must think beyond your prime and look to long-term performance and longevity.

How to Manage Oxidative Stress

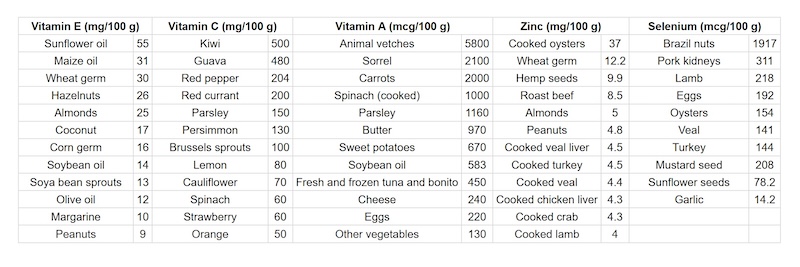

Like many challenges facing athletes today, a holistic approach is the best way to balance health and long-term performance. Antioxidants are the most effective way to reduce oxidative stress, and those from natural sources are the most healthful, in part because the doses are low. Look to eat at least five servings a day of colorful fruits and vegetables rich in antioxidants. Aim to eat fish twice a week to get omega-3 fatty acids, which are also integral to reducing oxidative stress.

The timing of nutrient intake can also help in managing excessive oxidative stress. For example, consuming antioxidants and carbohydrates immediately after intense training can help replenish glycogen stores and combat oxidative damage.

Image 2. Data Source: “Antioxidants and Sports Performance”

Prioritize recovery techniques like sleep hygiene and stress management. Mindfulness, meditation, and deep breathing exercises can all lower stress levels. Regular massage and foam rolling before and after training are non-negotiable parts of recovery. Limit your exposure to environmental pollutants and protect your skin from excessive sun exposure during training.

Regular blood tests for oxidative stress biomarkers can also be useful for effectively tailoring nutrition and training programs. Alongside performance metrics, assessments can provide valuable insight into athlete physical performance and recovery. Assessments can include more than physical performance tests. They should also consider subjective measures like mood, fatigue levels, and overall well-being.

Cross-training has increased performance and reduced the repetitive stress on the primary muscle groups used for sprinting, says Jack Shaw. Share on XSince oxidative stress presents differently from athlete-to-athlete, sprinters must monitor their responses to training and adjust accordingly. They must pay attention to signs of fatigue, prolonged soreness and decreased performance. They should then manage training intensity and recovery protocols around these symptoms.

Developing Training to Manage Oxidative Stress

Significant gaps still exist between science and best practice in how training methods should be applied for elite sprint performance. Excess oxidative stress further complicates matters, highlighting the value of tailored training programs compiled by experienced professionals.

Balance volume and intensity to allow for adequate recovery. You can do this by including interval training or tempo runs to push anaerobic thresholds while allowing for recovery. Incorporate easy runs, cross-training, and recovery to promote aerobic conditioning without excess oxidative stress.

Aim to train at a lower-to-moderate intensity 80% of the time, with 20% dedicated to more intense exercise. During intense workouts, your heart rate should be about 80% to 90% of your maximum, and you shouldn’t overexert yourself to exhaustion or nausea.

Active recovery days are also essential to promote blood flow and help clear metabolic waste products. Recovery days can include cold water immersion for 10-20 minutes between 50 and 59 F, which reduces inflammation and muscle soreness.

Cross-training has increased performance and reduced the repetitive stress on the primary muscle groups used for sprinting. Functional strength training is an excellent option to include for preventing injury and improving overall stability. Collaborating with sports nutritionists, psychologists, and expert trainers can give athletes a comprehensive approach to managing oxidative stress. Integrating multiple areas of expertise is crucial to developing a holistic strategy that addresses oxidative stress from different angles.

Creating a training program that manages oxidative stress is a holistic approach. It’s a balancing act between training, recovery, nutrition, and mental well-being. Athletes who find the sweet spot can optimize their performance while minimizing excessive oxidative stress.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF