When I was an athlete, at the end of each season I used to have my own mini review. I asked (what I thought were) probing questions: Did I meet my goals? Where could I improve? What was my goal for the following season? What performance was required to achieve those goals?

On the surface, this sounds like a useful exercise—an athlete taking ownership of their performance—and research demonstrates that realistic performance reviews are a crucial part of developing an elite athlete’s psychological toolbox. However, the mistake I made was that I generally didn’t forge a strong enough link between my performance review and the changes I needed to make to my preparation the following year.

The mistake I made was that I generally didn’t forge a strong enough link between my performance review and the changes I needed to make to my preparation the following year, says @craig100m. Share on XFor example, after the 2006 season, in which I struggled to perform at my best, my goal was to go to the World University Games in the 100m and challenge for a medal. To do this, I believed I had to be able to run around 10.25 seconds. My approach to this was, essentially, to train harder—I pushed myself in my key sessions, lost some body fat, and nailed down my sleep and nutrition habits.

In 2007, I had the best season of my life, running my personal bests of 6.55 seconds for the 60m and 10.14 seconds for the 100m. I made the semi-final of the World Championships in the 100m, won a bronze medal in the 4x100m, and won a silver medal at the European Indoors over 60m. My goal for the 2008 season was to make the Olympic final—I’m somewhat embarrassed to say that my approach to this was to do the same things I did for 2007, only better.

The Strategy Book

I don’t think my approach is uncommon; in fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if some athletes, and perhaps even some coaches, don’t even bother with a post-season review. My problem was in linking what had happened before with what I wanted to happen in the future via a coherent, planned, and systematic method of performance improvement.

After retiring from sport, I worked for a sports technology start-up; now I work for a national sporting organization. These companies have exposed me to different models and methods of doing business. A word often used in these settings is “strategy.” As someone without a strong foundation in business, I’ve had to spend some time getting up to speed with what a strategy is, what creating one entails, and how it can be useful.

One of the first books I read in this area was The Strategy Book by Max McKeown. As I made my way through its chapters, I started to see clear parallels between how businesses develop strategies and how athletes and coaches might use this information to better inform their planning process. The line between sport and business is continually blurred—and if you follow any sports coaches on social media, you’ll perhaps think it’s very overdone—but I remain convinced that The Strategy Book holds some useful lessons for us all when it comes to enhancing performance in sport.

When reading The Strategy Book, I saw clear parallels between how businesses develop strategies and how athletes & coaches might use this information to better inform their planning process. Share on XMcKeown says strategy is “…about moving from where you are to where you are to where you want to be … strategy is as much about deciding what to do, where to go, why, when and how as about choosing what not to do … Planning backwards for a better future.” A crucial aspect to keep in mind is that, as a starting point, strategy is not specifically about the detail (often that comes in an operational plan).

As Henry Mintzberg is quoted as saying, “strategy is not the consequence of planning, but the opposite: its starting point.” Strategy informs our planning, but then relies on individual actions and behaviors to deliver what is required—indeed, strategy execution is often considered far more challenging than actual strategy development and is where the best-laid plans often come undone.

Strategy, according to McKeown, is both analytical and creative. We have to understand where we are, where we want to get to, and what our competitors are doing—each of these requires some level of detailed analysis. We then need to be creative in our approach; what are some of the methods we can use to get from where we are to where we want to be? Finally, we return to analysis: How do we know if we were successful in achieving our strategic vision?

“The Strategic Self”

The first major section of McKeown’s book is dedicated to the strategist—in this case, that is you, the coach. Being able to develop a useful, comprehensive approach requires strategic thinking, which means we need to think before we plan. Specifically, McKeown provides four prompting questions:

- What do we want to do?

- What do we think is possible?

- What do we need to do to achieve our goals?

- When and how should we react to new opportunities and adapt our plans?

An additional large part of the planning process involves what McKeown terms “looking over your shoulder”—in business, this is understanding your competitors and markets. In sport, this is getting a better understanding of:

- Who your competitors are.

- What they do well—why are they successful? Commonalities between competitors may suggest that this trait underpins success.

- What do they do badly? What could we exploit to drive our own success? During my career, I ran against a couple of athletes who I knew couldn’t handle pressure at the end of a race; their game plan was to have an electric start and hold on. As a result, my strategy for these races was to put myself in a position where I could exert pressure on them from 60 meters onward, and then relax to move past them. Where are your opportunities?

- What do the best coaches and sporting systems in the world do? Or, perhaps more importantly, what don’t they do?

Let’s look at this through the prism of the coach of a promising 100m runner. That athlete has had some success at the junior level, making the World Under-20 Championships final and running 10.25. A crucial part of any strategy development is understanding what is required for success; in the 100m, this could broadly be defined as the interaction between stride length and stride frequency, and the underlying physiological and mechanical traits that contribute to both of these variables. Alongside this, we have to layer on psychological and broader physiological traits, such as the physiological resilience to tolerate the required volumes and intensities of training, and from a psychological perspective, compete well under pressure.

A crucial part of any strategy development is understanding what is required for success, says @craig100m. Share on XAn understanding of the required performance to achieve a specific outcome (such as a World Championships medal, final placing, semi-final placing, etc.) can assist in setting goals. From there, an evaluation of where the athlete is now—from a physiological, psychological, tactical, and technical standpoint—compared to what is required for these performance levels will guide planning.

“Strategic Innovation”

As I mentioned earlier, part of the strategic process requires thinking creatively. In sport, I’d argue that we don’t do this enough; we typically have set ways of doing things, and we unquestionably and uncritically accept them as valid. However, the veneer of many strongly embedded beliefs within sport is starting to crack. As an example, John Kiely has critically analyzed and appraised the research base on periodization theory. Periodization theory is a foundational bedrock of training theory, and yet some critical thinking suggests it is not as well proven as we initially believed.

Along this vein, McKeown has some prompting questions, which I’ve added to, for us to consider and reflect on—and which may drive our own thinking and planning innovations:

- Why don’t we change the rules?

- Why do we do what we do—do we know it works, or do we think it works?

- How do we know what we do works?

- Are we happy with the status quo?

- What would happen if we did something different?

- Why might we fail in our plan?

That last prompt is, to me, a really useful question, and is similar to the concept of a pre-mortem, popularized by Gary Klein. Here, we move ourselves into the future and ask, “Why did we fail?” By listing the various reasons, we can then take steps to mitigate the chances of those reasons for failure occurring.

Additionally, it is crucial to avoid developmental inertia, and a key quote from McKeown sums this up really nicely: “Success from doing what you are doing stops you from seeing what you should do next.” Similarly, a popular quote I’ve seen shared a number of times (not from McKeown) is “The most dangerous phrase in the language is ‘we’ve always done it this way.’” An important theoretical concept here is “what got you here won’t get you there”—but that’s another book entirely.

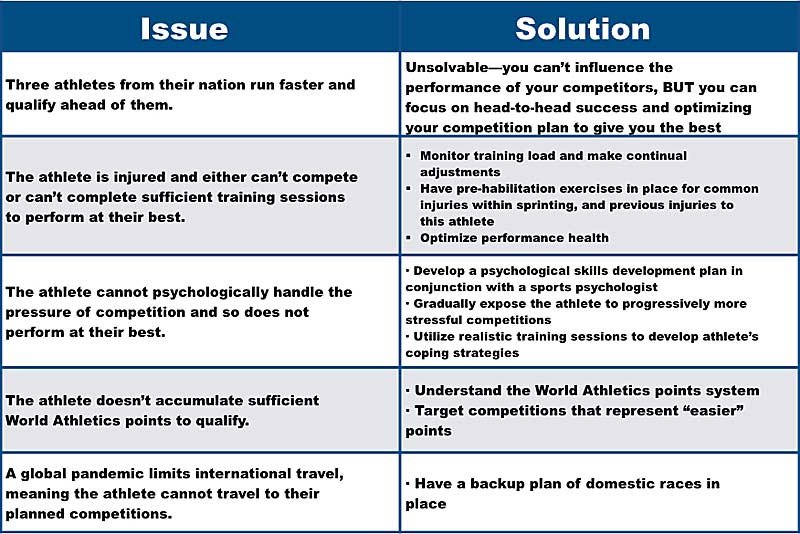

Again, let’s return to a sprints coach: Their athlete has a goal of running 10.10 for 2021, and qualifying for the Olympic Games in a quota spot (i.e., not an automatic qualifier). How might they fail in this? Here are some quick ideas:

- Three athletes from their nation run faster and qualify ahead of them.

- The athlete is injured and either can’t compete or can’t complete sufficient training sessions to perform at their best.

- The athlete cannot psychologically handle the pressure of competition and so does not perform at their best.

- The athlete doesn’t accumulate sufficient World Athletics points to qualify.

- A global pandemic limits international travel, meaning the athlete cannot travel to their planned competitions.

We can then consider some solutions to these, which can feed back into both the setting of strategic priorities and the development of a plan of action:

Know What You Can Do Best

Many companies know what they’re good at and aim to become market leaders within that niche. Google’s goal is to “organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” Obviously, Google started off as a search engine—a good way to make information accessible—but through being guided by this strategic goal, Google now owns YouTube (allowing them to make video accessible and useful) and has developed Google Books, Google Scholar, Google image search, and a plethora of other products to make information easier to come by.

Google even organizes our personal information through Gmail, Google Calendar, and Google Docs. By having a clear goal, Google developed a strategy that enabled them to be the best at what they do.

In sport, the end goal is more or less fixed: if we want to win the gold medal, we generally know what performance is required to achieve that. An important part of building your strategy is developing the process for achieving that performance. Once you understand the required performance and its constituent parts, you can then shift to better understanding:

- What is your relative strength?

- What can you do better than your competitors?

- Can you manufacture situations in competition to suit your strengths and expose your competitors’ weaknesses?

- How do you go from where you are now to where you want to be?

- Is it better to work on your relative weaknesses or focus on maximizing your strengths?

- How much of a threat are your weaknesses to your performance?

Don’t Just Plan—React!

It’s tempting to think that, once we have a plan in place, we need to stick to it. This is the wrong approach, writes McKeown. Instead, we should view our training strategy as an initial framework to guide us toward our goal; something we use to inform our plan. In this process, we continually need to update our plan with new information as it comes in:

- What’s working and what isn’t?

- How is the athlete responding to the plan?

- Do you need to spend more time on a given area?

- Can you recognize new opportunities that present themselves?

By accepting that we need to respond and adapt—daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly—we can be flexible in our response to this new information, while simultaneously, through our strategic plan, moving in the general direction of our end goal.

Making Decisions

Once you have an understanding of the general path you need to take to be successful, you must make some decisions, in the form of putting together a (flexible and adaptable) training plan. The decisions here are, essentially, what to put in and what to take or keep out. Through your analysis, you should know what the constituent components of performance are and, as a general rule, how good you/your athletes are at them at present.

The next step is to set priorities—what do you need to allocate the most time to work on?—and develop an understanding of how best to improve on them. Using this, you can create your training program, but you also need to consider:

- How will you know if what you’re doing is working?

- How will you know when to make a change?

- If something isn’t working, what changes will you make?

In this way, we enter the planàdoàreview cycle, with different cycles occurring on a daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly basis.

Do–>Review

An important part of the strategic process within businesses is to manage the ongoing delivery of the strategy, check for progress, and make changes. This process is so important that some companies have a chief strategy officer. Utilizing strategic thinking and principles within the athlete development process need not be any different; regular check-ins to ensure the training strategy is progressing as planned, and making any refinements, are crucial.

There can be different levels to this, ranging from quick trackside conversations to full-blown review meetings. An important part of regular review meetings is that everyone within the performance team should be able to have their say and provide ideas, giving a true 360-degree perspective on how things are progressing and ensuring new and innovative ideas are being brought to the table.

Danger Before Failure

In sport, it’s likely that your key strategic goal can occur only once a year (e.g., qualify for the World Championships), or perhaps even less frequently, such as winning a medal at the Olympic Games. Often, this means that there can be a lot of time between planning and knowing whether success has happened.

An important process…is recognizing danger signs that suggest you may be at risk of failing to meet your big goal, says @craig100m. Share on XAn important process during this time is recognizing danger signs that suggest you might be at risk of failing to meet your big goal. Part of the strategy process is understanding what systems you have to have in place to recognize that danger; it might be training load monitoring to identify periods of increased risk of injury, physiological testing of key traits, or stress testing the athlete in specific competition scenarios.

Each of these tests has the potential to identify risks to achieving the strategic goal and, crucially, buys you time to make any changes that may be required to get you back on track. Here, the key question is: “How will you know if you’re at risk of not meeting your goal?” The sooner you can recognize any potential danger, the more time you have to prevent failure.

“Strategic Tools”

The last section of the book is a collection of various strategy tools that may prove useful when developing your own strategy as a coach. One of these is the five basic strategy questions developed by McKeown, which should provide a starting point for much of your planning:

- Where are you now?

- Where do you want to go?

- What changes have to be made?

- How should changes be made?

- How shall you measure progress?

Other tools include:

- A SWOT Analysis—helping you identify strengths, weaknesses, and threats to performance.

- The 7-S Framework—allowing you to understand the strategy enablers you can use to deliver your training strategy.

- Kim & Mauborgne’s Four Actions—important in identifying what to keep, what to lose, and where to innovate.

- Kotter’s Eight Step Model of Change—often, part of delivering on a strategy requires managing a process of change, perhaps within yourself or with the athletes you coach. This model describes a process of working through that change.

Each of these tools may prove useful in developing a training and performance strategy, and so they are well worth looking at more closely.

Strategy Reminders

Strategic thinking can be complex and challenging, which is why the best strategic thinkers are highly prized by businesses. But I think McKeown’s book gives us some insight to develop our own framework to think strategically about how we develop athletes:

- Understand the event: In terms of performance, what does it take to be successful? How will this change over time—are performances stable or trending upward (or even downward)? Is the overall depth in the sport/event changing? How might any proposed rule changes or innovations affect this? How might the venue of future championships affect the required performance (e.g., heat, humidity, altitude)?

- Understand the constituent pieces: For a given performance (identified in point 1), what are the individual building blocks required for success (e.g., physiological, technical, tactical, psychological, social, etc.)?

- Understand where you or your athletes are now.

- Understand how to get from where you are now to where you want to be: What are the different methods that you can use to develop your key identified capacities?

- Think innovatively and question your assumptions: The more established the process, the more you should question it.

- Set priorities: Which area do you most need to improve in to achieve your goal?

- Understand what could go wrong, mitigate the key risks, and have a plan in place for responding to others.

- Set a plan.

- Understand how best to measure progress across different time points.

- Continually refine the plan, mixing short-terms goals and appraisals with a long-term vision.

Overall, this book is a crucial read for coaches. It sets out a framework for developing an effective long-term plan to drive performance success, which—when combined with other tools specific to your sport such as periodization and training theory (both of which you must critically analyze!)—will greatly assist in guiding you forward. I also think you need to give this book time: It’s a lot to take in on the first read, but rarely have I read a book that has had me highlighting sections so frequently.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF