If you are like me, when you first started in the sports performance field you had no idea what you were doing. And years later, you still have no idea what you are doing—you just have a better idea of what doesn’t work as well. I used to be a clean guy. I used to box squat. I bought all the bands, chains, and prowlers. They were good, and I developed strong athletes, but something was missing.

After years of trial and error, I was bitten by the speed bug. And bitten hard. I bought jump mats, timing systems, better prowlers, etc. I went all in. However, just like with the bands, chains, and months of trying to teach a clean, something was still missing.

My timing system was good, but I only got times—it did not reveal the full story of the sprint. Was this athlete a good starter? A poor starter? If I wanted to create force-velocity profiles, I had to buy how many more timing system units?

Even a prowler sled—a great tool for acceleration—has its flaws when it comes to individualization in a team workout. As coaches, we have all put one weight on a sled or maybe had the heavier sled and the lighter sled in a workout. The issue there was using the same weight for different athletes, with different body weights, heights, and abilities. For some it would be strength work, some power, and others speed work.

This year, as a change, I only worked with men’s and women’s ice hockey—in terms of specificity, there was now the issue of how to utilize the aforementioned tools on the ice. Timing systems present a similar challenge on ice, in terms of not telling the entire story of a sprint. Resisted skating on ice has its own unique challenges, such as how do you individualize and monitor loads and how do you stop a sled on a frictionless surface?

Resisted skating on ice has its own unique challenges, such as how do you individualize and monitor loads and how do you stop a sled on a frictionless surface? Share on XIt’s not that I had a problem, necessarily; it was more my tools didn’t provide the individualization, data, or instant feedback that I wanted. If you can handle the “Ninja Turtles” reference, over the last few years my Master Splinter has become Chris Korfist. I found him through podcasts, tons of articles on SimpliFaster, and his Track Football Consortium. If you are a fan and follower of Chris Korfist like I am, you know that he is a proud owner and promoter of the 1080 Sprint.

This machine could provide all of the things I was now wanting in my training.*

Getting to Know the 1080

When I knew my 1080 was on the way, I called Chris Korfist to ask for advice. He told me that the first three weeks I have it, I needed to create a velocity decrease of 50%, which would increase the athletes’ power production.

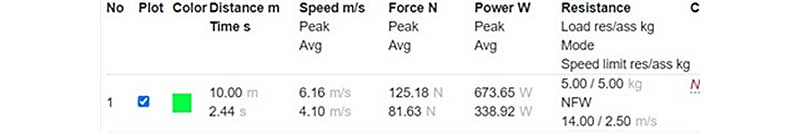

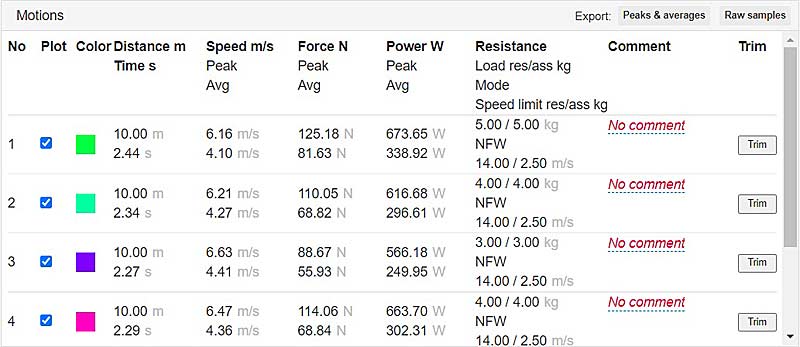

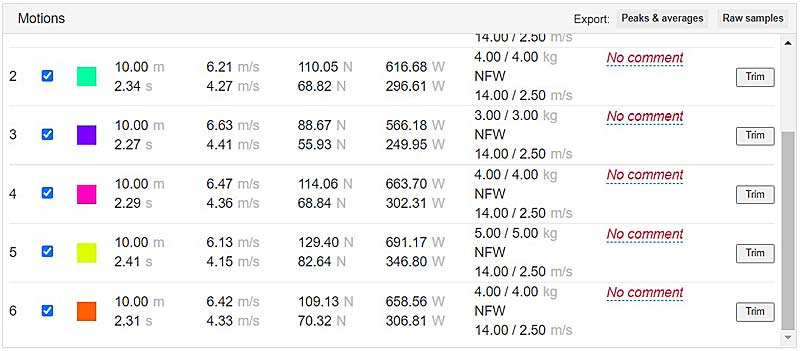

The velocity of a sprint is decreased by adding resistance—and we should try and have the highest resistance possible while only decreasing velocity by 50%. In the figure below, 5 kilograms of load is being used for this athlete to create a velocity decrease (not 50% though). He also mentioned basing things off averages because someone tripping could actually show a higher peak velocity (which I later found to be true). After a repetition, the tablet that operates the 1080 will give you a readout of:

- Distance and time.

- Peak and average speed (velocity).

- Peak and average force.

- Peak and average power.

Armed with Chris’ advice, I did some experimenting and familiarized myself and a few athletes with the unit. The 1080 Sprint has two gears of resistance. The first gear ranges from 1-15 kilograms of resistance and the second gear ranges from 16-30 kilograms. Second gear is smooth, and it is heavy, but it does not allow for as quick a transition from athlete to athlete. When you go into second gear, athletes cannot simply undo the belt around their waist and let the 1080 pull the belt back to the start line.

Second gear requires anchoring the line to an immovable object next to the 1080 unit and a pulley system tethers the line through the belt. If an athlete drops the belt and lets the 1080 pull it back in second gear, the line gets all wrapped up and around the pulley and you spend unnecessary time untangling it. The alternative is having each athlete sprint out in second gear, slowly walk backward to the start, then remove the belt to hand to the next athlete.

I decided to only use first gear to make transitions between athletes as quick as possible. This would allow more efficiency and more repetitions for athletes. Share on XWith only a one-hour workout twice a week in season as my training option, I decided to only use first gear to make transitions between athletes as quick as possible. This would allow more efficiency and more repetitions for athletes. Something to also keep in mind: These workouts were not just 1080 workouts—athletes were completing other strength and performance-related exercises within this hour block.

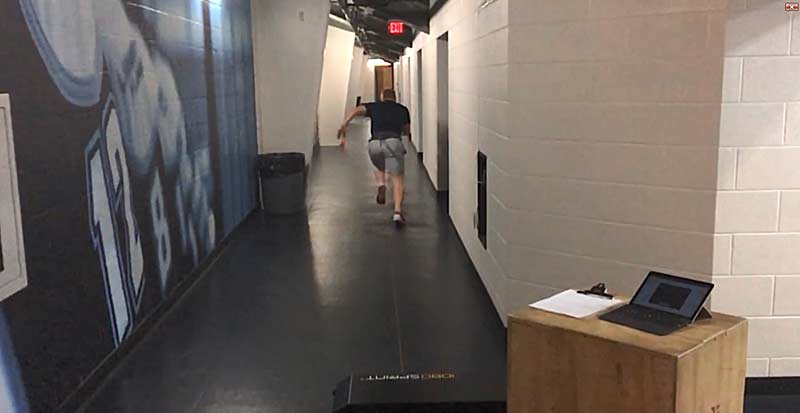

Video 1. Athletes demonstrating the workout flow with the 1080 Sprint in the Lahaye Ice Center hallway. One athlete completes a sprint and drops the belt, which retracts to the starting point. While this is happening, the operator should pull up the next athlete’s profile and make any necessary adjustments.

However, in first gear, the maximum resistance of 15 kilograms was not enough to get a 50% or even 25% velocity decrease. Uh oh. I had to use a 10% velocity decrease, which worked in first gear. Despite Chris’ advice of a 50% velocity decrease being optimal, in my setting it was not practical. If I were to attempt a higher percent decrease and use second gear, I feared I would not accumulate enough repetitions for a training stimulus. Instead of potentially getting 4-8 repetitions with a 10% decrease, in second gear I may only have time for 1-2 repetitions.

Next, after a few conversations with Vicki Bendus of Brock University, in an attempt to correlate on- and off-ice speed, I decided to have players utilize a crossover start both on and off the ice during training and testing. Excited to see what would happen from a three-week, 10% average velocity decrease program, I looked forward to January when the athletes would return from their winter break and start the spring semester. Once athletes got back, we would have more than 10 full weeks to prepare for Nationals in April.

Video 2. Athlete sprinting with resistance from the 1080 Sprint using a crossover start in the Lahaye Ice Center hallway.

Off-Ice, During Workouts

January finally arrived, and at that point, the women were the number one team in the country and the men’s team was in the top five. With the teams’ success to that point in the year, I was very cautious in introducing this new training variable. I was extremely elementary in my approach, essentially only using the 1080 for resisted sprinting, even though it is capable of so much more. Also, before running my velocity decrease program, I wanted to make sure all athletes felt comfortable using the unit, no one was noticeably sorer a day or two later, and that groins and hips could handle the resisted sprinting on top of all the skating they do in practices.

Here is the fun part of this semester… It was a coronavirus year semester, which means things never went according to plan. Both teams lost two weeks of training time due to a COVID-19 shutdown. We took all of our January and February training weeks to acclimate to the machine. These weeks were spaced out, again, due to a COVID-19 shutdown. Because of the inconsistent training and on-ice practices, it took much longer than anticipated to acclimate athletes to a point where I felt comfortable that my data would be valid and reliable.

After the athletes trained a bit and got familiar, in the first week in March, after weeks of getting used to the 1080 and with six training weeks left before Nationals, we began a 5- to 6-week program. Here’s how each week looked:

- Week 1 – Two workouts where athletes ran 10 meters, crossover start, 1 kilogram of resistance. The highest average velocity was then taken, and a 10% decrease was calculated to be used for the next three weeks.

- Week 2-4 – One to two workouts a week. Athletes ran 10 meters and resistance was added or subtracted to get the athletes as close as possible to a 10% average velocity decrease.

- Weeks 5-6 – Two workouts a week where athletes ran 10 meters, crossover start, 1 kilograms of resistance. The highest average velocity was compared to the highest average velocities from week one.

Weeks 1, 5, and 6’s testing days were simply mixed into a normal workout. That is the beauty of the 1080 Sprint: the training is the test; the test is the training. I collect useful data, more than just the time, on every single repetition, and it is all individualized.

During the training cycle, all of the athletes followed the same template for their workouts:

- Either a split squat or trap bar deadlift.

- A weighted or unweighted jump.

- A single leg assistance exercise, such as an RDL or step-up.

- Individually resisted, 10-meter sprint with a crossover start.

After they completed their single leg exercise, they would walk out into the hallway of the ice rink and perform their resisted sprint there. I had a designated 1080 operator who would add or subtract resistance based off the player’s previous average velocity in order to maintain a 10% average velocity decrease. The goal for the players was to use the highest resistance possible.

Results

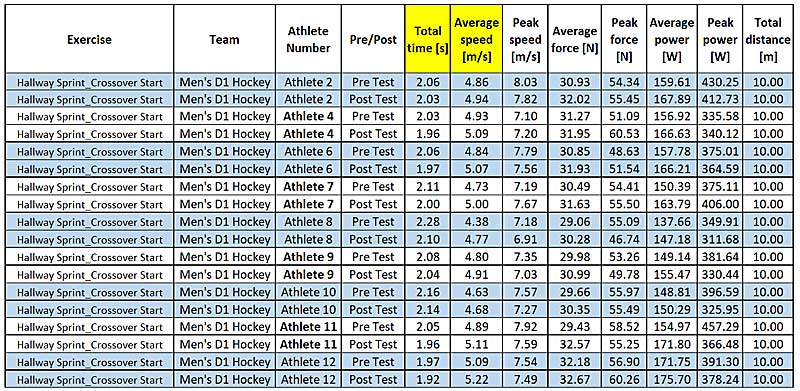

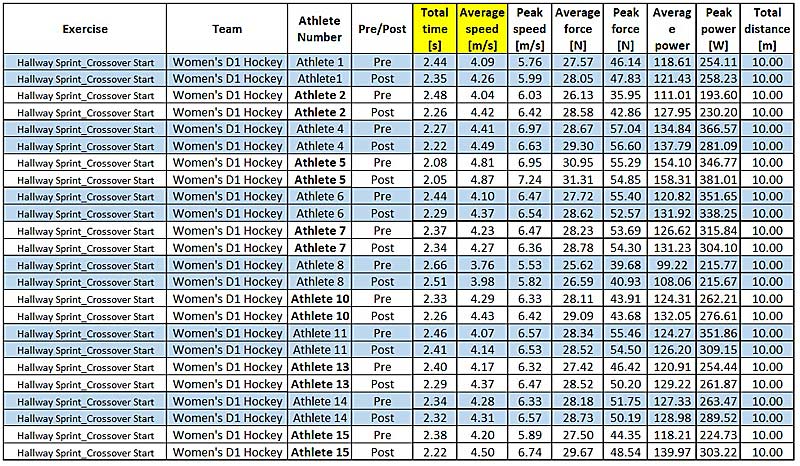

After three weeks of sprinting with a 10% velocity decrease, here are the results for the men’s and women’s hockey teams.

Of 15 men who finished the program, nine saw improvements in their time to 10 meters, as well as their average velocities.

Of 15 women who finished the program, 12 saw improvements in their time to 10 meters, as well as their average velocities.

On Ice

In the entire spring semester, I was able to get seven on-ice sessions, measuring 60 good repetitions. I did not pull away any conclusive data from these, unfortunately. They were too spread out and sporadic throughout the semester. This was not executed as planned—I was hoping for more ice time, but that is not always how it goes.

To test and train athletes on ice, I brought the 1080 to the end of the ice surface, where the ice cleaning machines come out of (the “zam room” for those who speak hockey). I simply used an extension cord to bring the 1080 to the edge of the ice and was fortunate that the lip of the ice surface was just low enough that I could set my 1080 on the ground off ice and it was fine. I ran the unit by sitting in a chair on or off the ice surface. Players typically skated 30 meters, which is from the goal to mid-ice.

Video 3. Athletes skating with 1080 Sprint, using a crossover start, in Lahaye Ice Center.

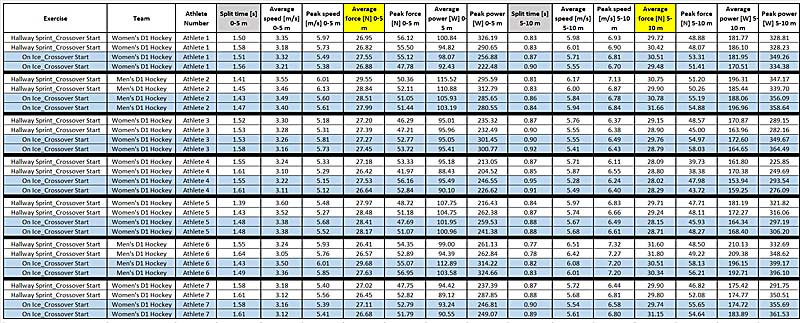

Despite all of this, when the hockey seasons ended, I compiled data into an Excel sheet to compare on- and off-ice force production, something I was always curious to investigate. To do this, I broke each 10-meter sprint down into 5-meter splits. I wanted to know if athletes’ forces on ice were similar to off ice, in the hallway of the ice rink. In my mind, this would indicate transfer from the hallway to the ice.

I only analyzed 1-kilogram resisted sprints, and hand selected off-ice times to be near on-ice times. For example, Athlete 1 has a personal best 10-meter sprint off-ice of 2.10 seconds, but I selected one of their 2.33 second sprints to compare to a 2.38 second on-ice sprint.

The chart below displays two off-ice and two on-ice 10-meter sprints, with 1 kilogram of resistance and a crossover start. I found it very interesting that despite wearing ice skates and being on ice and wearing equipment and holding a stick, the force production numbers were not far off when comparing on and off ice.

Furthermore, I found on the ice that it was best to use first gear instead of second gear. Second gear was so heavy their stride simply broke down too much. Next, I realized it was easiest to have the players attach the carabiner at the end of the 1080 cord to the loop on the back of their hockey pants.

This was very interesting to me. I thought it would be easier to use the same system as we did in the hallway: one person goes, drops the belt, and the next person puts the belt on.

However, when it comes to having gloves and sticks, it got complicated. On top of that, after reading an article he wrote about the 1080 Sprint, I reached out to Jacob Cohen, Illinois University’s sprints coach.

Jacob mentioned that he does not use the 1080 as a timing system because his athletes are so dialed-in that the belt throws them off, and it may get in their head. I felt like I was experiencing the same thing with my hockey players—despite wearing tons of equipment, they were using the belt as a crutch for a potentially poor time. Therefore, we used their loops instead.

Key Takeaways

First, this experience reestablished in my mind how much athletes love to compete. Whenever a time or certain metric is put to a sprint, everyone competes. Whatever you make a big deal out of, the athletes make a big deal out of.

Resisted sprinting also proved to be extremely valuable for improving acceleration. Sprinting in first gear, dropping the belt, and having it retract is a very efficient way to run larger groups through on the 1080 Sprint. It gives the tablet operator time to click to the next athlete and add or subtract necessary resistance.

Sprinting in first gear, dropping the belt, and having it retract is a very efficient way to run larger groups through on the 1080 Sprint. Share on XFinally, it seems the forces produced on the ice are similar to the forces being produced off the ice in a 10-meter sprint. This further leads me to believe there is a direct transfer between off-ice and on-ice speed.

Thoughts for the Future

As I look ahead, over the summer I plan to utilize more of the overspeed capabilities of the 1080 Sprint. Keep in mind we were in-season this entire semester. The last thing I could do is risk injury. This summer, I planned to have one or two days where we sprinted overspeed.

On ice, I plan to distinguish training and testing days. On testing days, I may pull the timing system back out for ease of setup and efficiency in running athletes through. On the training days, I may set the 1080 up on a bench and only have players skate 10-15 meters, or the width of the ice. This will make it easier and faster to get it out there, set it up, get the training in, and then I may easily close the bench door. With that setup, I may be able to get players through for 20 minutes before or after a practice.

Other considerations are, what happens when COVID-19 restrictions are over? How will I use this when I have my full 24-26 man/woman roster? For now, I am thinking of something like splitting the team into two groups: one group for speed and power focus, and the other for strength and accessory work.

For those wondering about the results of the teams at the end of the semester, the men’s team lost in the semifinals and the women won. Top 4 and National Champions. Not too bad.

*Author’s Note: Fortunately, through a miracle, Dr. Jared Hornsby of the Allied Health Professions Department reached out in Summer 2020 and asked if we would be interested in conducting research using a 1080 Sprint. I said yes. Through Dr. Hornsby‘s hard work, and convincing my AD it was worth the investment, my 1080 arrived on campus a few months later. I’m very grateful to Dr. Hornsby for his efforts on our behalf.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF