One of the most important components to any training program is the intent with which the movements are performed. You can have the “best” program with the world’s top technology, but if the drills are being performed with lackluster intent, long-term results will be minimal at best. One of the most effective ways to maximize intent is to find ways to measure what you’re doing. A big thing I’ve added to my training programs over the last year is more consistent measurements and specifically drills that can be measured.

A big thing I’ve added to my training programs over the last year is more consistent measurements and specifically drills that can be measured, says @JoeyBergles. Share on XI work primarily with junior high and high school athletes (12-18 years old). When a sprint is being timed, a medicine ball throw distance is being recorded, or a jump distance is being measured, the intent of the subsequent drills goes up substantially. It’s a very reductionist statement, but that is what will drive adaptations. For me, if I can have drills done with a consistently high level of focus and intent, I feel confident that long-term progress will be made.

Making It Work in the High School Setting

Now, the difficulty with this concept is that, like most high school S&C coaches, I’m working with anywhere from 30-110 athletes at one time. This obviously presents some unique challenges, especially when you don’t have interns or a sports science department.

I’ve had to find some unique ways to structure things so that there’s good flow and we’re still able to measure what I want to get measured. There might be a circuit where we’ve got four different drills going with 100 athletes. That doesn’t mean that every drill is getting measured and recorded, but in that example, there might be a jump distance measured, a sprint being timed, and then two other drills that make up the rest of the circuit.

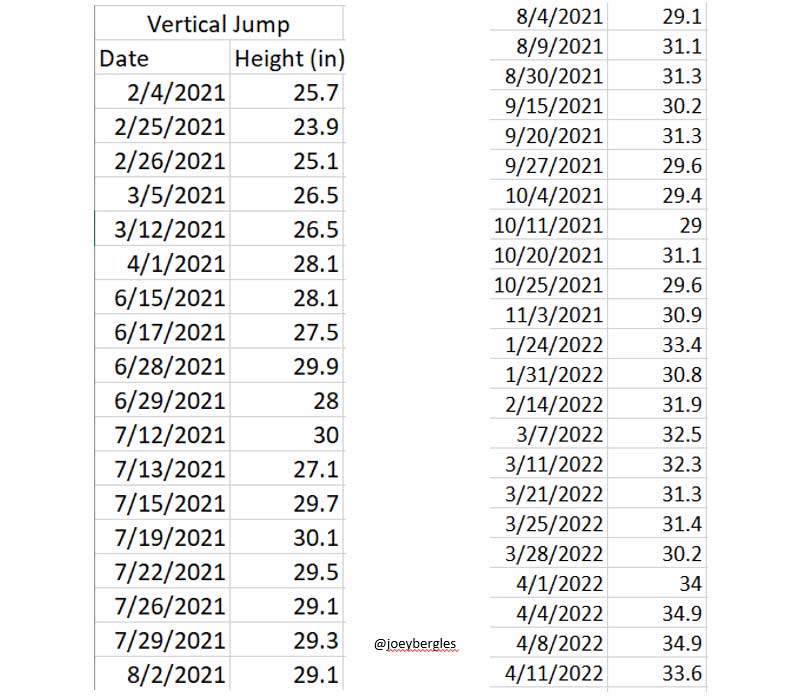

I do different types of medicine ball throws, different sprint variations (acceleration and MaxV), and various types of jumps (both horizontal and vertical). There are some things measured weekly and others that might only be measured a couple times a year. The benefit of this, though, is that I can look back to last year and see, for example, what an athlete’s seven-hop distance was—even if we haven’t done it in six months.

I keep a digital record board in my weight room for both boys and girls. The following are the tests on display:

- Vertical jump

- Broad jump

- 2+10-yard sprint

- Flying 10-yard (boys: 30-yard build; girls: 20-yard build)

- Medicine ball overhead throw (6-pound MB)

- Curve sprint (custom – standardized)

What I’ve Dropped

This all leads into what I’ve dropped out of my program, which makes all of the above possible: I no longer personally record numbers. All of the measurements that are tracked within our S&C program are 100% the responsibility of each individual athlete. We’re lucky to have the software that we do that makes that possible, but even if we didn’t have it, I would find a way to use Google Sheets or something similar.

I no longer personally record numbers. All of the measurements that are tracked within our S&C program are 100% the responsibility of each athlete, says @JoeyBergles. Share on X

As coaches, we always hear about “the process,” and a big part of my process involves athletes taking ownership of their respective performance numbers. If I ask an athlete what their best vertical jump is, I don’t want them to have to look at a sheet that says what that number is. I want them to know what it is, because if they know what it is, that means it matters to them—and when something matters to someone, they generally work harder and perform the work with more intent.

Also, when they’re doing that test, if they hit a PR, they instantly know it. That’s the long-term process since there won’t be PRs every session. When they do happen, though, it means something. It means all the work they’ve been putting in has led to a specific result.

In addition to junior high and high school, I work with younger kids, and I’ve got fourth graders who can tell me the time for the best flying 10-yards they’ve ever run (which likely happened six weeks ago, not yesterday). If 10-year-olds can remember something, I don’t believe it’s a stretch to think that most high school athletes can remember what their best performance numbers are.

I’ll give two examples regarding how athletes recording their own performance numbers works in practice:

-

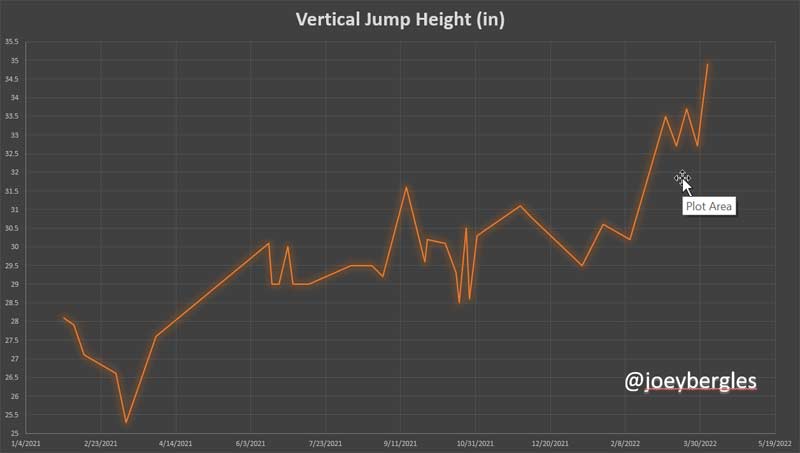

- Vertical Jump. First off, we use jump mats. I either have vertical jumps performed with our main movement or after they come into the weight room following speed/plyometric work. The athlete steps on the jump mat and jumps. Either a coach or a player calls out their number is (e.g., 30.6 inches). The athlete is told what their jump was. They then go into the system for that day and input their vertical jump number into the system. If they know coming into that session that their best vertical jump was 30.2 inches, they instantly know they hit an all-time PR, which is a big deal.

- Flying 10-Yard. We use Freelap and have 20 chips. Athletes run their flying 10-yard. A coach stands at the end of the run and calls the time that the athletes ran while they’re coasting out of the sprint. Normally, we run anywhere from 1-3 reps. I tell the athletes to remember what their best time of that session was, and then they input that number into the system. Say coming into that session their all-time best was 1.03 seconds, and they run 1.06 and 1.02; that 1.02 was better than they’ve ever run before, so again, another PR.

I like to think I’m pretty detail-oriented. With testing, there are a lot of details that can be overlooked that affect the results of the test, such as taking a small approach step on a jump or starting 2 inches behind the line on a 2+10-yard sprint. (Two yards is the fly zone—any additional distance affects the subsequent time and now makes the test unstandardized.)

These are all things I routinely bring up with my athletes, so that when they’re performing the tests, we’re always standardized. First and foremost, I want accurate information. That allows us to see long-term trends. When I look at a piece of data from eight months ago, I need to assume that data is accurate and the test was performed how it should be.

I’ll be honest, this is a huge challenge when dealing with hundred of athletes. With that said, though, I had (85) eighth grade girls do this exact thing with their broad jump and vertical jump numbers. It saves so much time and allows so many more tests to be performed on a regular basis.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF