[mashshare]

There’s been a lot of progress in the speed training world lately, with plenty of coaches using shrewd methods and seeing impressive progress with player speed development. It is a little disappointing that some attempts in new principles of training are not based on actual logic or reason, just conjecture and a lot of speculation. If you want to improve speed, you need to be better at measuring it properly. You also need to have a great way to evaluate interventions or methods when time and energy are at a premium.

If you want to improve speed, you need to be better at measuring it properly, says @spikesonly. Share on XThis article is not about what I believe is the truth or best way to develop speed; it’s about ensuring we all start on the same page first. It makes a strong argument for using conventional speed training to get faster, and shares what those methods are. If you are serious about athlete development and want to make sure you do everything you can to improve your athletes, this is the best springboard you can have.

Global Speed Beats Specific Speed

The Science for Sport podcast was the inspiration for this article, as a short discussion there likely created more questions than answered them. Most of the problem with sports performance education is that it consists of opinions without research or internal evidence. I keep hearing the term “game speed” versus track speed and instead of getting frustrated, I wanted to stop the unnecessary debate and get to the heart of the matter.

Simple expressions of linear speed are necessary to see how athletes are able to transfer what they have into a game or competitive situation.

What I mean by this is that many sport science research studies point to intermediate effects of training, as a soccer player’s improvement of their 20-meter sprint time may not show up in a game. I realize that running faster in a straight line may not make an athlete more successful all the time, but if the improvement in speed doesn’t seem valuable, where are all the receivers in the NFL with great routes and hands and horrible speed? The fastest linear athletes may not make the team, but show me a terribly slow athlete in pro team sport where their position requires running fast.

Why do people worry about fitness at all when fatigue reduces speed, you ask? It doesn’t make sense for someone to dismiss linear speed because it’s not perfectly connected to a game condition, when any loss in speed would be seen as catastrophic. Those who don’t believe in speed enhancement should ask themselves if they were to put a 4-kilogram vest on their athletes, would the athletes object? Of course they would have a problem with it. So, if you are not developing speed, it’s like you are putting a philosophical weight vest on the athlete for development. Global speed is like taking off the invisible weight vest and evening the playing field.

This is likely the fifth or sixth time I have brought up the ketchup analogy for training, mainly because each time I explain it, coaches tend to overthink the other areas too much and keep repeating the same logical fallacies. If you want more ketchup (performance) you need more tomatoes (speed), not more tomato juice (specific practice only). When you spend most of the year competing and practicing, underpreparing and mimicking the sport takes away from the already scarce amount of basic training.

Competitive opportunities are not rare in most sports. How many times have you seen pickup games of soccer or basketball? How many travel teams and club teams are there? Countless! Are seasons and tournaments for professional sports decreasing? No. There’s plenty of time to play, but not much time to prepare. So, if you have time to prepare, attack speed if you can.

If you have time to prepare, attack speed if you can, says @spikesonly. Share on XSometimes there’s an overreaction to, or misinterpretation of, “just get strong” or “don’t touch a ball” by those who feel uncomfortable outside the weight room or as a straw man argument. I think it’s wise to blend phases to ensure no shock to the system occurs, like only working on linear speed for months, then playing a game. My only concern is that we forget that general training must take place or not enough change will happen in a short period of time. When resources are scarce, the key is to prioritize what is important. Innovation occurs when scarcity exists, as it forces thinking that is rational and creative for a clear purpose.

Speed Kills, But How Dangerous Is It?

One practice that I give some praise to is the work of trying to get athletes better later in their careers. Similar to in-season training, many coaches bring up “in-career speed development” as a point of contention for addressing sprint velocity. Keeping the athlete “healthy” is unnecessarily popularized and shortsighted.

What is even more confusing is the medical idea of making athletes “robust and resilient,” but it has yet to be determined who is really doing this and what the real results are with injury rates. If an entire league spends their time wanting to reduce injuries and maximize performance, why do some teams do it well one year but then it changes the next season? The answer lies with variables the support staff can’t control, and that’s why speed development is so hard. If an athlete doesn’t want to try to get faster, you can lead them to water but you can’t make them drink, so to speak.

The next step to understanding how much additional speed is important is addressed well in Martin Buchheit’s great blog post on beetroot supplementation. Ironically, a sport science statistical lesson is also a great discussion of what is truly a worthwhile change, as simple metrics like horizontal speed may matter to coaches if they can truly be replicated in applied real-world settings. Speed improvements that show up on the field and make a difference in tangible sport metrics outside of general running speed are a holy grail. Think about teams that win the ball all the time and truly capitalize on scoring opportunities. If a team is significantly faster and fitter, and can use those advantages, then the training is worth it.

Coaches may care about metrics like horizontal speed if they can be applied in real-world settings, says @spikesonly. Share on XSpeed reserve does have a limit though, as Usain Bolt won’t win a marathon even though his speed gives him an advantage on paper. Genetically, a compromise exists, and while you can say the same about endurance giving an athlete a potentially great finish in sports that have a stamina element, a triathlete’s ability to augment speed is limited to improving their sport ceiling, not converting the athlete to another sport. The potential to be more competitive in sport is confined by one’s genetic ability, and if little room is available, then not much should be expected from training. Most of the time, an athlete continuing to work on speed is smart because maintaining an ability over the years is just as difficult as seeing improvements later in the development phase of a career.

I believe most teams don’t know how much time-distance matters besides the sports clichés such “a game of inches” and so forth. If it’s truly a game of inches that makes the difference, then 20 centimeters is worth fighting for. Eventually an athlete can’t get faster with limited training days as time itself becomes the enemy. In summary, added speed usually becomes a weapon when other areas are not compromised. It may not be that a team is faster—they may just be playing faster because they are not too tired or they maintain power better than a “faster on paper” team. Technically smart players play fast, but if a player is smart and physically fast, they’re more likely to win.

What Is Peak Sprint Velocity?

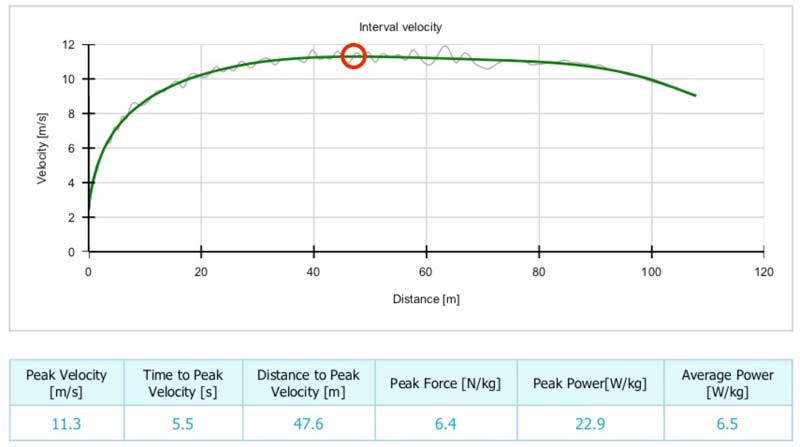

Defining peak sprint velocity (PSV) is very easy: It’s how fast you can sprint. What confuses a lot of strength coaches when they read GPS numbers (speed readings) after practices or games is that they rank athlete speeds based on who has the fastest number. Without enough runway or distance, it’s hard for an athlete to achieve peak velocity.

A child may pick up their speed and accelerate to their peak velocity in a matter of steps. An elite sprinter needs more than 6 seconds or near 50-60 meters to hit peak velocity. While an athlete may achieve close to their top speed early—say 30 meters—they do need additional distance to get to a true maximal velocity.

PSV is not repeated sprint ability, as that quality is more about acceleration and the endurance to reduce the decay of velocity. An athlete’s peak speed in running is nothing more than a slice of time—even one or two steps— but it’s extremely valuable to know. Knowing how fast they can sprint in terms of velocity is a useful measure, as it represents the ceiling of speed and the rest of the velocities underneath are all affected. Speed reserve and even acceleration all connect to peak sprint velocity. Having the simple number of an athlete’s maximal running speed is super valuable, but you need to know the best way to measure it.

What Is the Best Way to Measure Peak Sprint Velocity?

I can list a half dozen ways to calculate peak sprint velocity, but what is possible and not practical won’t likely be used when a group of athletes show up to practice. For example, a simple radar gun is useful in training as it will display peak speed, but it only shares a slice of time with little context. A laser is better because it’s continuous and live with distance readings, but even the best measurement tool needs the right testing protocol or it’s just guess work of what is really going on.

HS athletes sprinting with short acceleration distances doesn’t test PSV—it tests late acceleration, says @spikesonly. Share on XHaving high school athletes sprint with short acceleration distances is not testing peak velocity, it’s testing late acceleration. Both the right equipment and the right testing procedure are necessary to determine how fast someone really is. Starting with the right strategy to capture peak velocity is paramount, and that enables you to decide on the right equipment. You can capture peak velocity with just a smartphone app, but if you want to train with peak velocity readings, manual methods are simply not practical.

Usually a coach tries the split “fishing net” approach (timing gates) and not the laser “spearfishing” option. When coaches get splits, they are estimating the peak velocity reading because they assume the athlete is running a constant speed during the 10-meter segment. A split time, or the velocity extrapolation, is really an average of what was likely run. A true peak is the absolute highest speed, not the average speed during a peak zone or split. How much of a drop-off it is matters less at elite levels because their peaks are longer and smoother, but if you use a split approach with the wrong athlete, then you are usually capturing a slower speed. You can create your own velocity bands with split times, and several companies provide a solid timing solution for this.

Two reasons this occurs are that most coaches are afraid to time segments from 40-50 meters, and most athletes don’t accelerate in a patient manner. If a fast athlete in team sports, or sometimes track, learns to accelerate uniformly, they are more likely to hit a higher speed. Just like a talented acceleration in sprinting having poor abilities to hold top speed form due to psychological issues, race modeling, or training errors, a team sport athlete is likely to be ill-equipped to run comfortably at maximum speed because they have less awareness and comfort with this quality. If you don’t rehearse something, it’s hard to be effective or polished.

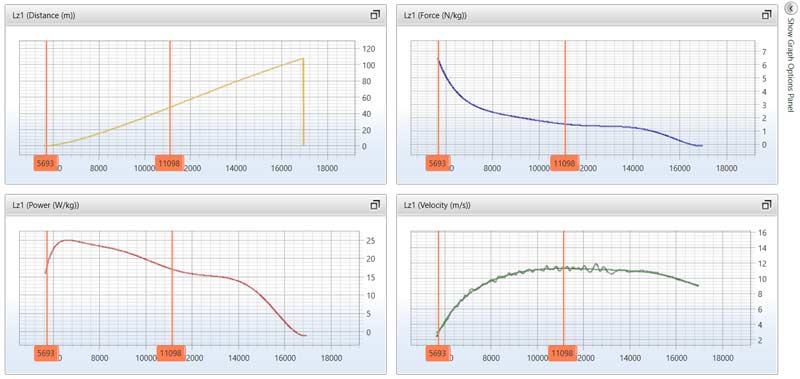

Using a laser is ideal for several reasons, but my best rationale is that the entire curve is collected, meaning not only does the device gather acceleration, but also the more important deceleration. I don’t mean change of direction (more on that later), I mean the decay of speed. While peak sprint velocity is likely king of speed metrics, the second in line is perhaps fatigue rate. It is very useful for everyone to know how an athlete accelerates, when and how fast they hit PSV, and their pattern of slowing down.

Jumpers have taken advantage of laser technology for nearly 30 years at some Olympic training centers, and now all athletes can use it to practice. If you want to test PSV, nobody can use budgeting an excuse, as Dartfish offers a way if you are good with video. Again, however, the slice of information from video is hard to train with live. I recommend not only a laser, but adding video or a contact grid where possible. Simply put, I love the PSV metric and want everyone to access it regardless of budgeting, but if you want to have better practices to improve it, the laser is everything now.

Training Top Speed – Options That Work

There are three common approaches for training speed and two methods: either attempting to hit maximal velocity in a fly, or running slightly slower with less effort. You can go longer distances or you can go fast and contrast it with smoother runs called “ins and outs” or “sprint-float-sprint.” Besides those methods, some coaches have used less direct methods, such as weights, jumps, and drills to get athletes faster. So far, very little research has been able to decipher what works and what doesn’t, and much of the methodology out there in the speed world is speculation. Still, enough support from experienced coaches is sufficient to come to a fair agreement that sprinting at top speed or near it in some form is helpful, and every option has its pros and cons.

Flying Sprints: A common approach that is pretty vanilla is accelerating to a zone that requires the athlete to hold a speed for a set distance. The distance of the flying sprint usually ranges from 10-30 meters in length, but some have been 5-meter peaks for just a few steps while others have been longer fly distances ranging from 30-50 meters, on average. The goal of the flying sprint is to hold the same speed, so most longer flying sprints are slower than the shorter options.

Overdistance: Some coaches use much slower and far longer sprinting to build endurance and some make an argument that the lactate accumulation teaches relaxation effectively. It’s difficult to see how using this approach exclusively can increase peak velocity if the sprinting is always slower, but with racing schedules and competitions influencing athletes, a case for submaximal intensive tempo or faster workouts does make sense.

Ins and Outs (Sprint-Float-Sprint): Another useful method (and in my opinion, the most underrated when done properly) is this combination workout of technical and maximal sprinting. The sprint-float-sprint workout is the most compelling way to get athletes faster because it features a set of raw speed training components surrounding a technical phase of sprinting. Athletes using “ins and outs” workouts are exposed to great speeds and periods where speed is mechanically controlled.

Other indirect and secondary methods may have a contributing effect to top speed, but without basic running programs those methods likely won’t be useful for a broad range of athletes. Coaches have used an array of techniques, but for the most part, the three listed above are the most common and effective ways to get athletes faster. How effective? Time will tell. My guess is that, over time, the power will come from the coaching crowd and we will know from better record-keeping and meet performances in the sprints. For team sports, it will be tougher to find out, but I am confident peak velocity readings will migrate to faster outputs in the near future.

What About Acceleration and Change of Direction?

Given the nature of most sports as having short bursts of acceleration and a lot of movement that decelerates, it’s natural that there’s a debate over the importance of peak sprint velocity. To squash this argument, let’s discuss the realities of practice time. Does anyone make top speed a weekly priority and adjust all other training elements accordingly during the season and careers of athletes? Probably not. Speed is always coveted and acquired through recruiting, drafts, and transfers, but it is rarely developed systematically over time by the collective sporting world. It’s almost to the point where a coach needs to shelter athletes from the chaos of performance training and competition to actually improve peak speed qualities.

Speed is coveted, but rarely developed systematically over time by the collective sporting world, says @spikesonly. Share on XThere has been an ever-growing discussion on exposure, or how much interaction an athlete will need to have in game conditions. Coaches have seen lateral speed and linear speed as related qualities, and not so dissimilar that they must be trained radically different. True, most specialized sprinters don’t have the skills to make many athletic change of direction movements without help, but take a football player with a sprinting background and he is weaponized. Linear speed may not always be accessible, but when it is, the combination is extremely valuable.

Theoretically, a development model for athletes should use linear speed as its backbone, and lateral motion, agility training, and sport participation as its limbs. All are necessary in team sport, but expecting just playing or technique development of footwork to be a solution is a bad idea. Countless years of agility or change of direction rehearsal have backfired, likely from the fact humans are designed well to walk and run, but we are not equipped well for agility. The human ankle, for example, is superior in propulsion forward, but it’s less effective laterally. Working on change of direction or an athlete’s movement abilities is a part of the development equation, but it’s likely a smaller part than coaches want to believe.

Measure Your Athletes the Best Way You Can

The goal of this PSV article is to explain how to interpret the data and see the big picture in athlete development. We coaches are enamored with peak velocity on a ball or barbell, but if we were to ask how fast someone runs, unfortunately we usually mean a 40 time or, worse, a distance run. Not everyone is going to agree with me, but I see a lot of coaches getting excited about flying sprints and timing sled workouts.

If there is one takeaway from this closing argument, it’s that the best way to evangelize change is with simple algebra, not exotic biomechanics, molecular physiology, or specialized anatomy. Faster athletes have an advantage, and global speed abilities should be a cornerstone, not merely something nice to know. In the past, team sports were concerned that track coaches were training team sport athletes like “sprinters.” Now that we have been vindicated, they can see the logic has value.

Global speed abilities should be a cornerstone—not merely something nice to know, says @spikesonly. Share on XYears ago, I was scared to time peak velocity with athletes because I knew if something happened it would be a death sentence for the relationship. However, going rogue has paid off immensely. I don’t care what you use for evaluation, but I do care if you are avoiding the proper assessment of speed.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]