Are athletes prepared for return to sport? The current evidence suggests “no” based on reinjury rates and decreased performance upon return.1–7 I struggle with this problem myself and was looking for ways I could improve. The easy answer was to measure workload. On the performance side, workload is often used to make sure athletes aren’t overtraining, with player availability being so important. However, on my side (rehab), I would use it to make sure I was not underloading athletes.

The easy answer to determine if athletes were prepared for return to sport was to measure workload. On my side (rehab), I would use it to ensure I was not UNDERLOADING athletes, says @MuyVienDPT. Share on XWhen I investigated current tracking methods, I realized how daunting the cost could be to purchase a unit for each of my athletes. This is not a surprise, as for many, cost is consistently a barrier with the continuing emergence of improved technologies.8

Can’t I just grab athletes’ units from their performance coaches? This is logistically challenging since the units may be charging, uploading data, or in use, or there may be other time constraints that would affect when they are provided/returned. This does not solve the problem for practitioners working with private clients off-site, and it made me get creative.

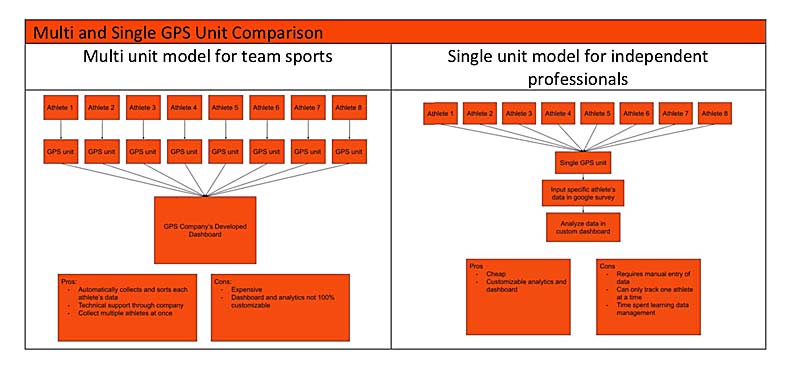

What if I could design a system where I only needed to purchase a single unit? To answer that question, I sketched out the plan (figure 1) and made it work.

So far, so good. I have been very happy with my little system—it has changed the way I practiced by answering the question I was looking to answer. Since my system serves me well, I thought I’d share with others in a similar position. Yes, you can always just open the raw files to view; however, my method will hopefully save you time by having your data automatically calculated to get you to the meaningful measures that will answer your questions with external and internal load.

My method will hopefully save you time by automatically calculating your data to get you to the meaningful measures that will answer your questions with external & internal load, says @MuyVienDPT. Share on XIn the long term, this method should streamline and enhance a practitioner’s operations; in the short term, however, developing it does require an investment of time and mental resources.

What You’ll Need

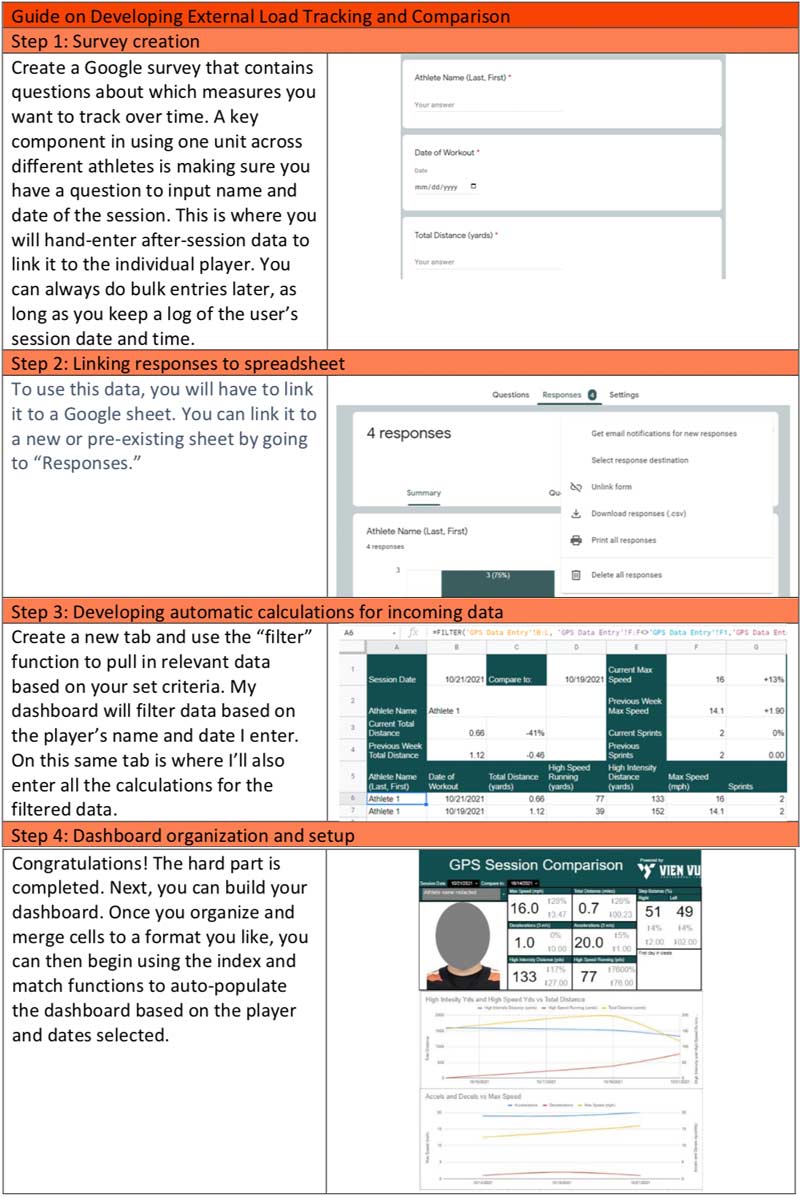

Here is a guide to the overall steps coaches can use to set up a system that uses a single GPS unit to track and present the data of several athletes (figure 2).

Google Account or Excel

This method requires collected data to be dropped into a spreadsheet. For this reason, Google services work best since it is online. However, users can also link responses to an Excel file. If you use this for sports medicine purposes, be sure that the services you use are HIPAA compliant. G-Suite is a very cheap service that allows you to use secure Google services. If you plan to use Excel, you’ll have to make sure it is saved on a secure server, emailed using encryption, or shared through secure Microsoft Teams services.

GPS Unit

There are many different options, and this article may help you decide which unit is best for you. Each product has different measures of workload, so it would be best to purchase the same device that most of your athletes use when returning to their teams. You may also factor in what you use it for. For example, I went with STATSports Apex Series because I use the live data to dictate my sessions. You can have live data with other devices, but they may require you to spend more money on local positioning Systems (LPS) units. The Apex Series also does not work indoors, while LPS systems do.

Again, the previous linked article can review the nuances. Be sure to pay attention around the holidays, as some devices can drop from $300 to nearly $180. Lastly, the most expensive portion will be the vests. They cost about $40 a piece—you may luck out like me, and your performance coaches may have old ones they can give you. If you are using it for back-to-back clients, you will need multiple quantities of the sizes; however, I only use it with 10–20% of my clients per day, so I can wash them between uses. All in all, you have plenty of options and will need to purchase one unit.

Two to Four Hours’ Time Investment in Learning Google Sheets/Excel

This is the most time-consuming portion; however, it will be the gift that keeps on giving. For the sake of the proposed system in this article, individuals will need to know how to use three functions: filter, index, and match. There are SO many resources out there, but my favorite tutorials are from Adam Virgile. Not only does he have easy-to-follow directions and tutorials, but he is a sport scientist who understands what you may want to do with data relevant to sports performance and rehab. By watching the videos linked below, you should be able to build the same system proposed in this article or an even better one:

One to Two Hours to Build the Dashboard

Once you have the physical and mental tools, the actual process should only take you a couple of hours to set it all up.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9062]

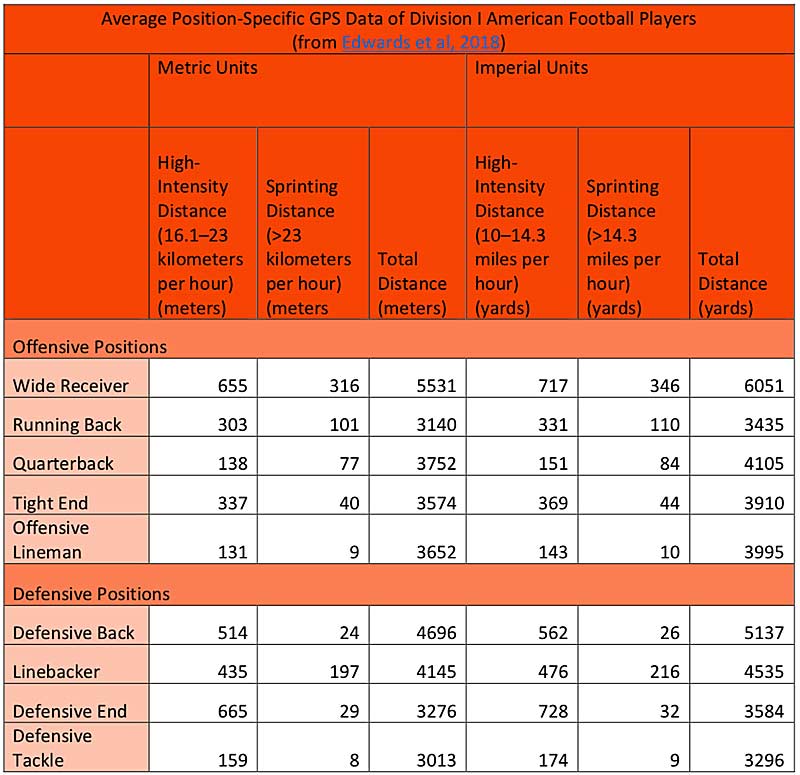

External Load

Below is a guide on how I look at external load. I personally value other metrics over “player loads.” Instead, I want to look at changes over time and between certain sessions. The trade-off is that I would be unable to compare that athlete to the team’s demands with that specific metric. However, I feel like I can do well with other metrics and normative values found in research (figure 3).9

Additionally, I want to look at the relationships between certain measures. Did I increase athletes’ max speed and decrease their total distance? Did I ramp up their high-intensity distance but decrease their training time? Did their step balance even out at high speeds? These are all questions I wanted to consider when building my dashboard.

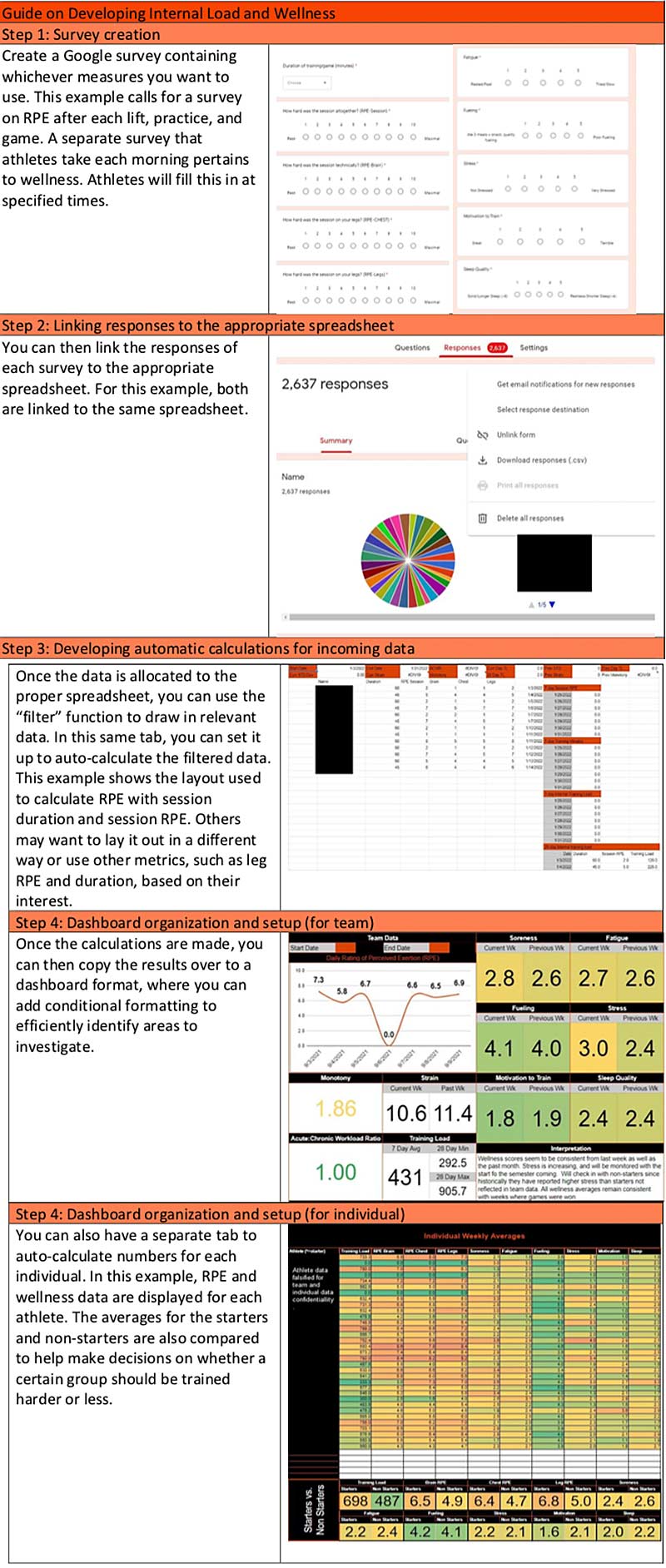

Internal Load

What about internal load? At the time I looked into what tech I should purchase, none of the teams I worked with tracked heart rate for internal load. Instead, most used session rate of perceived exertions (sRPE), which has shown to be valid and reliable in measuring internal load.10 You can read here how to capture and effectively use internal load without the cost of heart rate monitors. Because I could not relate my external load to the team’s data, recording RPE and wellness responses helped me have some kind of measure to compare the athletes to their teams.

You can apply the same concept to developing a method to track internal load and wellness (figure 4). Current methods of wellness measures do have their flaws, as described in this article; however, collecting responses on a numerical scale makes it easier to calculate. A comment section can always be added as well.

Pearls

All right, you did it. You now have a good understanding of the steps it will take to pull this off with minimal costs. Before you start, I’m going give you advice based on all the mistakes I made. These are not only the mistakes I made while developing this system in the beginning, but also hindsight at the end of the year when I began analyzing data for season-end reports. That’s right, this advice can save you HOURS of formatting changes and MONTHS of valuable data!

- Constraints mean easier data cleaning and process: It looks much cleaner when everything is uniform, and data may be missing from your calculations if there are grammar and/or syntax errors. I would recommend making your response options pre-defined including athlete’s names. Otherwise, you may have to deal with constantly cleaning “MaryPoppins,” “MaryPopins,” “Mary P,” or “MP” if the athlete makes typos or inconsistencies.

- Try to change everything to a numerical scale: Because your calculations require numbers, you want the responses to be entered as numbers too. This skips a potentially very time-consuming step to convert data. Although there is a trade-off, as described in this article, you can at least start with objective data before refining your methods.

- Track compliance: If all your players are not compliant with their responses, it may skew the data or make it outright invalid. There are likely many ways to do so, but personally, I have a separate tab that displays the dates of each person’s entries, so I don’t have to sort and sift through entries.

Also, those who are NOT compliant should not be punished. Many athletes do not like entering and filling out our surveys, so getting punished with conditioning or cleaning will increase their hatred for entering wellness data. Instead, have devices ready for them after lifts and practice in case they did not fill it out on their own via cellphones. Educate them on what you hope to do with it.

- Organization and planning are key: Take a look at other people’s dashboards to see what you like. Once you make your dashboards, it can be hard to add new things because of formatting. Lay out a grid and label which cells will contain which info. Despite that, just know you will likely make new iterations.

- Do something with the info: Dashboards and data are a hot topic right now. Everyone seems to be collecting massive amounts of data, but few are using that data.11 What will you do if athletes have low energy? Would you target your intervention to the team or to the individual? Who is in charge of implementing said plan? Are there proactive measures? How often does follow-up data get taken?

There’s a reason there are entire sport science teams and PhDs dedicated to this field. This isn’t to deter you but keep you aware of the sports science field’s complexity and that measuring workload is just one aspect.

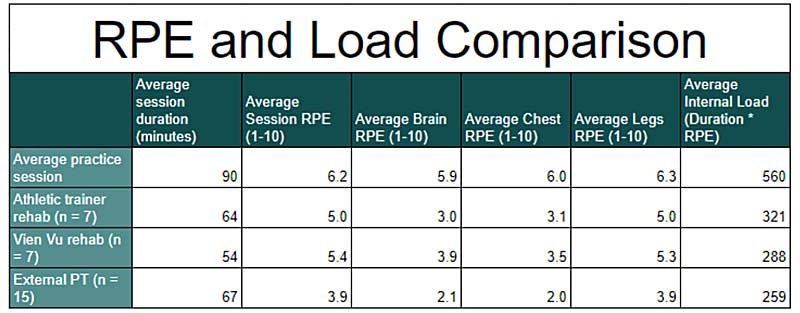

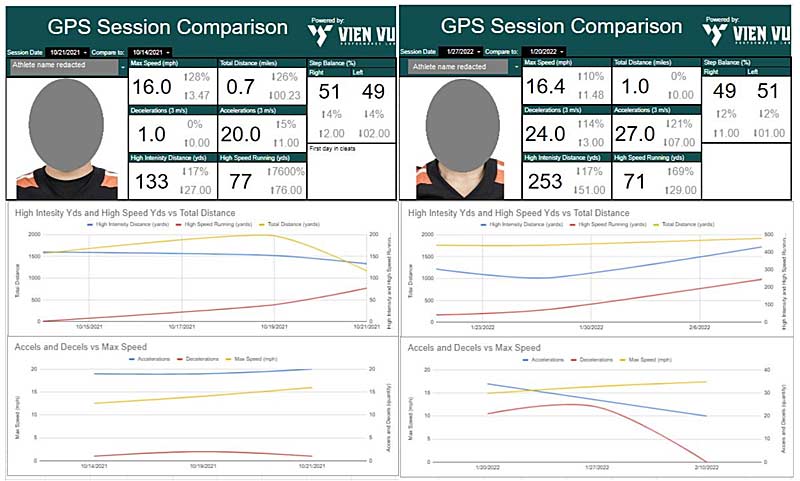

In my examples above, my method allowed me to make changes to my practice to achieve what I wanted. In early-stage anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehab, when athletes can hardly walk, I am still able to induce a “hard” session compared to the mid-stage rehab of the control (external PT) by modifying session pace, exercises, and session format (figure 5). In another example (figure 6), I was able to use the same GPS unit to track and display meaningful metrics for two athletes while only spending two minutes entering data after their sessions.

Conclusion

I hope my transparency with the process provides an efficient and cost-effective way to implement workload management to objectify decisions on the field, says @MuyVienDPT. Share on XWorkload management does not have to be labor intensive or expensive. The field of sports science continues to grow, and an active effort to understand it can enhance practice.11,12 Although my system is not rocket science and is likely already done by many, I hope my transparency with the process provides an efficient and cost-effective way to implement workload management to objectify decisions on the field.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, and Webster KE. “Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;48(21):1543–1552. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093398

2. Ardern CL, Webster KE, Taylor NF, and Feller JA. “Return to the Preinjury Level of Competitive Sport After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Surgery: Two-thirds of Patients Have Not Returned by 12 Months After Surgery.”American Journal of Sports Medicine. Published online November 23, 2010. doi:10.1177/0363546510384798

3. Dai B, Layer JS, Bordelon NM, et al. “Longitudinal assessments of balance and jump-landing performance before and after anterior cruciate ligament injuries in collegiate athletes.” Research in Sports Medicine. 2021 Mar-Apr;29(2):129-140. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2020.1721290. Epub 2020 Feb 2. PMID: 32009460; PMCID: PMC7395857.

4. Webster KE, Klemm HJ, and Feller JA. “Rates and Determinants of Returning to Australian Rules Football in Male Nonprofessional Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. Published online February 11, 2022. doi:10.1177/23259671221074999

5. Wiggins AJ, Grandhi RK, Schneider DK, Stanfield D, Webster KE, and Myer GD. “Risk of Secondary Injury in Younger Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. Published online January 15, 2016. doi:10.1177/0363546515621554

6. Kotsifaki A, Rossom SV, Whiteley R, et al. “Single leg vertical jump performance identifies knee function deficits at return to sport after ACL reconstruction in male athletes.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. Published online February 7, 2022. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-104692

7. Jae C, Jj M, E K, Kaj D. “Vertical jump impulse deficits persist from six to nine months after ACL reconstruction.” Sports Biomechanics. Published online September 21, 2021. doi:10.1080/14763141.2021.1945137

8. Stevens CJ, McConnell J, Lawrence A, Bennett K, and Swann C. “Perceptions of the role, value and barriers of sports scientists in Australia among practitioners, employers and coaches.” Journal of Sport & Exercise Science. 2021;5(4):285-301. doi:10.36905/jses.2021.04.07

9. Edwards T, Spiteri T, Piggott B, Haff GG, Joyce C. “A Narrative Review of the Physical Demands and Injury Incidence in American Football: Application of Current Knowledge and Practices in Workload Management.” Sports Medicine. 2018;48(1):45–55. doi:10.1007/s40279-017-0783-2

10. Halson SL. “Monitoring Training Load to Understand Fatigue in Athletes.” Sports Medicine New Zealand. 2014;44(Suppl 2):139. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0253-z

11. Rauff EL, Herman A, Berninger D, Machak S, and Shultz SP. “Using sport science data in collegiate athletics: Coaches’ perspectives.” International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching. Published online January 21, 2022. doi:10.1177/17479541211065146

12. Hewett TE, Webster KE. EDITORIAL: “The Use of Big Data to Improve Human Health – How Experience from Other Industries Will Shape the Future.” International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2021;16(6):1590-1594. doi:10.26603/001c.29856