“There is no such thing as overtraining, just poor recovery.”

— Shane Sutton, Former Technical Director of GB & Team Sky Cycling

Whether professional athlete or weekend warrior, their desire is to perform their given sport or activity to their optimal levels. To achieve this level of realization in their chosen craft there is no alternative but to practice, practice, practice, and then do more hard work. Athletes undertake training loads so that they, through physical and psychological over-loads, improve their body’s ability to achieve a personal goal in a race, squatting performance in the gym, or pitching performance from the mound.

However, if they don’t accurately manage these levels of workloads, it can cause “overtraining” via too many high-intensity loads and/or too much poor athlete regeneration. Sports/training loads and “life” stressors such as poor quality of sleep, sport or business travel, poor nutrition choices, and weight loss can all affect the well-being of the athlete and push them into a downward spiral of acute fatigue, over-reaching, overtraining, subclinical tissue damage, and time lost to injury and illness.1,2

Many competitors work hard and push their body’s limits while also wanting to continue exercising day in and day out, without much thought given to their need for recovery and/or regeneration modalities until they fall ill or become injured. Yet, although “regeneration” is an extremely important piece of the “athlete performance jigsaw puzzle” and a balanced training schedule, it is very often the forgotten element.3,4,5

Solving the Overtraining Conundrum

In my previous role as a performance coach with professional teams, I oversaw the care and well-being of as many as 30+ athletes. The important lessons I learned are that we are not all the same and we do not respond in the same manner to workloads or recovery.

For instance, soccer games were on Saturdays (although sometimes there were mid-week games), and Sunday was generally a travel day back from a game or a recovery day. On a recovery day, players performed “active recovery” (light to moderate loads), followed by hydrotherapy, vibration plate stretches and movements, and the wearing of compression apparel to aid with blood flow. I educated athletes on the importance of a good night’s quality sleep, good nutritional choices, and the timing of that nutrient intake.

Depending on the time within the season and number of minutes played, some players may still not be fully recovered for intense workloads during team training sessions on a Tuesday or Wednesday. These players may need longer warm-up or preparation protocols before joining their teammates. You may also need to hold them out of team loads on that particular training day and have them work with the performance coach in a one-to-one or small group setting so you can more easily monitor and support them.

No two athletes will respond in the same manner to exercise workloads and recovery practices. Share on XTherefore, there are three main components to this overtraining conundrum and your ability to steer the athlete/weekend warrior down the right path:

- External loads (their physical load);

- Internal loads (physiological or perceptual responses);6 and

- Athlete regeneration practices. External loads include measures such as distance run, speed, weight lifted, and even internal loads that capture heart rate, rate of perceived exertion and regeneration practices, and use of modalities such as hydrotherapy, nutrition (timing), compression items, quality sleep, massage, and vibration plates, to name a few recovery routines.

Work Hard + Recover Well = Best Performance7

Exercise loads alone will not achieve those personal goals or results, as everyone from the elite to “middle-aged warrior” needs time to adapt to training stimuli and allow sufficient recovery from fatigue or depletion of the physiological and neurological systems involved. Unfortunately, there can be no “one size fits all” mentality, as no two athletes will respond in the same manner to the exercise workloads and recovery practices.

Thus, careful monitoring and tracking of training sessions, external and internal loads, and either observations by a qualified coach or careful self-evaluations (such as recording resting heart rate, noting the quality/quantity of sleep, body weight fluctuations or feelings of consistent tiredness) allows for an understanding of the athlete’s ability to cope with the demands set in the training program. Which regeneration processes are most effective will probably depend on individual preferences and is most likely a combination of practiced methods.8,9

An Athlete Case Study with Major League Baseball

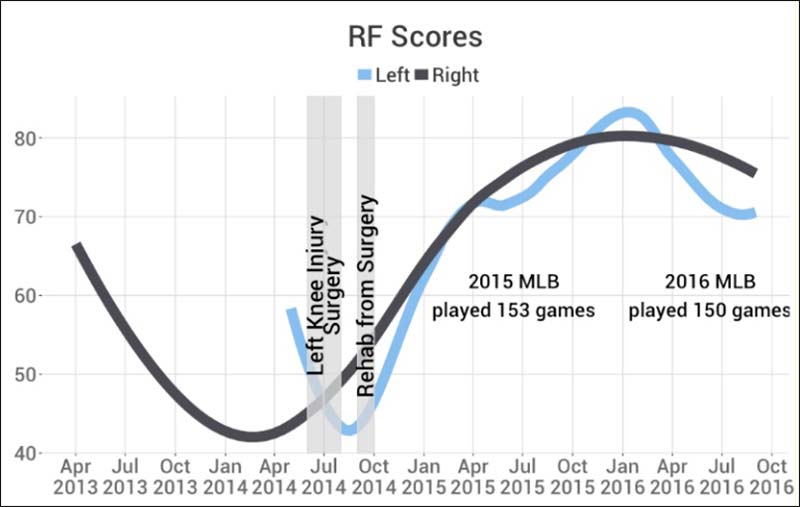

Now, while an acute injury is more easily identifiable, injuries related to overuse are a culmination of repeated loads leading to tissue maladaptation and they occur gradually over time.2 These overuse injuries can appear in many varying forms and are associated with, among others: biomechanical variances due to insufficient loading patterns; extended muscle soreness/tenderness; depletion in muscle energy/health values (Chart 1); various biomarkers showing decreased hemoglobin; decreased serum iron; mineral deficiencies; varying mood swings; flu-like symptoms; swelling of lymph glands; and more.

I worked with this baseball player over the last four years and collected the data in the chart starting in 2013, and going through a seasonal downward depletion of muscle energy values. There were low scores during spring training in 2014. Then, in June 2014, the player suffered a left knee injury resulting in season-ending surgery. August was recovery/rehab from surgery, and the data shows further muscle energy depletion.

During the off-season, the player committed to a re-tooling of his physical conditioning and made improvements to his nutritional intake and timing. By 2015 spring physicals, both RF muscles had a score of 70, emphasizing the improvement in muscle fuel content and muscle health. Now the player had confirmation that all the demanding work was paying off, along with improved nutritional choices and a focus on regeneration protocols. He played in a career-high number of games during 2015 and 2016; all injury-free.

MuscleSound’s patented software and technology enabled the collection of this muscle health data, which gives an athlete the opportunity to take charge of their muscle health. Monitoring muscle health allows for the appreciation of the readiness of the athlete. As mentioned earlier, this readiness is always a balancing act between the physical responses to workload (games/training) and the regeneration from these efforts. MuscleSound technology, along with the collection and analytics for each competitor and team’s objective data, should enable informed assessments on each individual’s race readiness and health status.

Parting Thoughts on Recovery and Overtraining

In summary, overtraining and poor recovery are about managing exercise workloads and following regeneration strategies to help combat those major causes of fatigue. Always include nutritional intake and timing, quality sleep (as sleep disturbance after a game/race is common and can negatively impact recovery), and the utilization of various recovery modalities in your strategies.

Frequent MuscleSound analysis and other biomarkers help in the detection of athlete readiness, fatigue levels, inflammation, and potential muscle damage. Athletes and exercise enthusiasts that follow the “Work Hard + Recover Well = Best Performance” equation will benefit the most, with more optimal performances and better health.

References

- Drew, M.K. & Finch, C.F. (2016). “The Relationship Between Training Loads and Injury, Illness and Soreness: A Systematic and Literature Review”. Sports Medicine. 46: 861-883.

- Soligard, T. et al (2016). “How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee Consensus Statement on Load In Sport and Risk of Injury.” British Journal Sports Medicine. 50: 1030-1041.

- Bompa, T.O. (1983). “Theory and Methodology of Training”. Kendall / Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque, Iowa.

- Brown, R.L. (1983). “Overtraining in Athletes – A round table”. Physician and Sports Medicine. 11: 93- 110.

- Kuipers, H. & Keizer, H.A. (1988). “Overtraining in Elite Athletes – Review and Directions for the Future.” Sports Medicine. 6:79-92

- Gabbett, T.J. (2016). “The Training – Injury Prevention Paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?” British Journal Sports Medicine. 50: 273-280.

- Reaburn, P. & Jenkins, D. (1996). “Training for Speed & Endurance.” Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd. 9 Atchison Street, St. Leonards, NSW 1590 Australia.

- Al Nawaiseh, A.M., Bishop, P.A., Pritchett, R.C., & Porter, S. (2007). “Enhancing Short-Term Recovery After High Intensity Anaerobic Exercise”. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 39: s307.

- Jakeman, J.R., Byrne, C. & Eston, R.G. (2010). “Efficacy of Lower Limb Compression and Combined Treatment of Manual Massage and Lower Limb Compression on Symptoms of Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage in Woman.” Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 23: 1795-1802.