Recently, my wife and I went on a crazy new adventure called “having our second child.” Yes, it was a huge blessing…but with some complications in the birthing process, our little angel was stranded in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) for about a week. That meant multiple trips to the hospital each day to see her, lots of quiet time watching her hooked up to tubes and machines, and many conversations with nurses about her health and progress.

The last point is the inspiration for this article. For those of you unaware of how our medical system shift-work functions in Canada, there are two shifts: day and night. Days are 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m., while nights are the opposite. With our little girl there for multiple days, it meant that every 12 hours, there was a new nurse overseeing her station. Yes, over the course of a week, we had the same nurse multiple times, but I would say that over her seven-day stay, there were at least five different caretakers responsible for her care.

While every single one of these nurses was excellent at their job—and the level of care that our daughter received did not dip from one to the other—the way in which my wife and I experienced the care did change slightly based on who was on staff.

You see, each of the staff was excellent in their care of babies, with years of experience in that area. But one thing separated some from the rest—some had kids of their own, while others did not. Each nurse knew how to follow the protocols for our daughter, but those with children of their own had a different way of communicating with us as parents. It is hard to explain, but there was more empathy for us and more integration of us into the process. To give you an example, one nurse (who had kids) allowed us to take our daughter’s temperature and change her diaper while she was sedated, whereas later in her recovery, another nurse (who didn’t have kids) didn’t offer the same.

We got excellent information when speaking to these non-parent nurses, but it wasn’t delivered in a way that related to us 100%. I told my wife after the fact, “It felt like we were talking to a textbook.” Great information, but limited applicability outside of the hospital and what would happen for us next.

The same can be said for sport coaches in the youth system as far as those who have kids and those who do not. There is just something different about coaching when you have lots of experience interacting with kids, understanding their common issues/needs and how to handle them when they freak out. Now, it obviously isn’t necessary to have kids yourself before coaching youth sports, but similar to the nurse example, there is a deeper level of understanding for the whole process from those who do.

What is the whole point of this story?

While reflecting on the process in the hospital (and youth sport coaches), it struck me how similar this situation is to us as strength and conditioning coaches. There is a frequent debate in the S&C community as to whether you need to have played the sport you coach. As the Head S&C Coach at a Canadian university, I coach multiple sports, of which I have experience playing only a few. I was on the side of the argument that said you did not have to play the sport to be the best coach and get the best results for your athletes, as that was my reality.

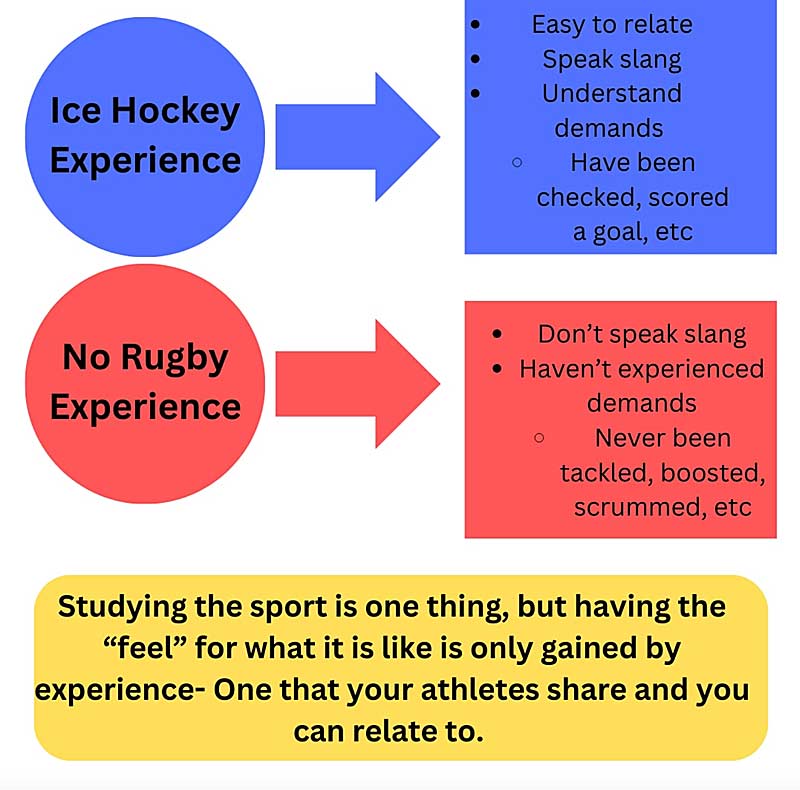

While I still stand by that thought, my stance has softened a bit after this recent experience with my daughter in the NICU. You see, when working with a certain team, you can research that sport all you want. You can understand the rules, know the common injuries, and look up the energy systems at work. However, just as the childless nurses had a different feel and understanding than the nurses who had kids, even though they both knew their stuff, coaches who haven’t played the sport aren’t exactly like coaches who have.

You Can’t Play Them All

Once again, I currently work with eight sports and have only played four competitively. Does that make me a poor strength coach for those other four sports? No (well, at least I hope not). But for those four sports I have competed in, I feel more confident coaching, more confident using their language, and more confident relating to the players.

While I’m not a poor strength coach because I’ve only played four out of the eight sports I work with, I feel more confident coaching those sports’ players and using their language, says @chergott94. Share on X

Many of you might be in the same boat when it comes to the sports you currently work with. The whole point of writing this article is not just to highlight a gap you may have in your coaching but to help you address this issue since I know it is a common one. As S&C coaches, we often dream of working in the top league of our chosen sport. For example, when I first started, I wanted to be an S&C coach in the National Hockey League (NHL). I later fell in love with the university side in my undergrad and have never looked back.

Pursuing this path has automatically put me in a position to coach athletes on teams for sports I did not play. As an S&C coach, you might find yourself in the same situation, whether working at a university with multiple teams like me or with a single sport that you have not played. So, how do you start to bridge the gap in your knowledge and understanding to help you speak their language and fully get through to your players? Let’s take a look…

1. Start Playing the Sport (or at Least Practicing It)

This one might have jumped out to you right away. If you have never thrown a baseball and are working with a baseball team, that might be a good place to start. Yes, there are plenty of recreation leagues you could join for almost any sport, which means if you really wanted to dive in, you could become an athlete and learn the sport firsthand as you coach the team. For myself, with two kids, a wife, and multiple sports to learn, that wasn’t something that I could feasibly do.

What I have done is tried and practiced the skills of each of the sports. For example, we recently added disc golf to our varsity sports portfolio, and I had never really seen disc golf played, let alone thrown a disc myself. So, after researching the sport and understanding the mechanics, I figured I had it down pretty good. Then, our disc golf team invited me out to play a round with them toward the end of the season.

Wow…what a humbling experience.

Not that I misunderstood the rules of the sport or had the mechanics wrong from my “textbook learning,” but there is something much different than reading about it—and that is actually doing it. For example, the rotation of throwing a disc is much different than I anticipated. I am used to throwing frisbees, swinging a bat, and taking a slapshot, and none of those skills helped me with this. It was a whole other beast that I had to learn firsthand how to do, which in turn made me better at coaching exercises that helped it. It enhanced my “feel” for the sport, not just my brain knowledge. Plus, having the athletes see me fail at something and continue to try and learn was also great for buy-in.

Spending a few minutes each week refining your skills can help you understand the demands of the sport better and, therefore, your message on how to improve it, says @chergott94. Share on XThe same goes for any sport. Practice shooting free throws, taking corner kicks, or working on your jump serve. Spending a few minutes each week refining your skills can help you understand the demands of the sport better and, therefore, your message on how to improve it.

2. Study the Terminology of the Game

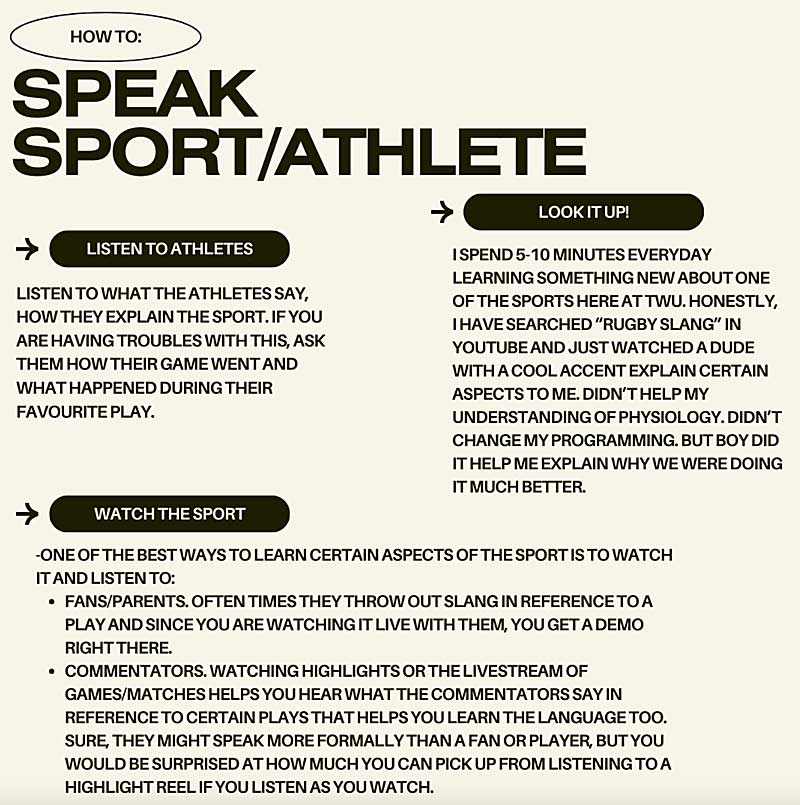

Another way to help yourself communicate better is to study the language of the sport. Yes, volleyball rallies last roughly 30 seconds with 30–60 seconds of rest, but did you know that if someone is “libbing,” they are playing libero, or that giving the ball a “tug” is slang for spiking it?

While these are not crucial to know for you to be a great S&C coach, by learning the language and better understanding the psychology of the sport, you can improve the way you relate your message to the team. Instead of saying the reason you do upper body strength work for hockey is that “We want you to have the strength to take hard slapshots and score lots of goals,” you can say, “We want you to be able to crank a howitzer bar-cheese from the hash”—then you are speaking their language, having more fun with it, and in turn increasing their buy-in because now they are thinking this guy/gal gets it. And, as we know, even if your program doesn’t change, if the effort put into it does, that is a HUGE win.

So, how do you learn the slang?

3. Ask Questions (Be Humble)

One of the best things I have done to help myself understand the language of sport more is to simply be humble enough to admit I don’t know and ask my athletes (or coaches) questions. Something I did over the COVID-19 year was arrange a meeting with each of our sport coaches, asking them to explain the way we play/train so that I could hear how they explain it. This helped me understand our systems better and helped me learn their language, which, in turn, created a more unified message to our athletes and helped them make the connection from the weight room to the pitch/track/court/ice.

Another thing I still do is frequently ask our athletes about their sport. I want to learn more, and the best people to explain it to you are those you want to explain it back to. That way, you can hear their language/slang and remember it when you explain it.

Another thing I do is frequently ask our athletes about their sport. I want to learn more, and the best people to explain it to you are those you want to explain it back to, says @chergott94. Share on XAs a simple example, when I was running a speed session for our men’s rugby team on our pitch a few weeks ago, I wanted them to start at half and run to the next line on the pitch. But before I simply pointed and said, “Run to there,” I asked a couple of the guys, “What do you guys call that line?” Their answer? “The 10.” So now my message was, “I want you guys to start at half and sprint through the 10.” It might not seem like a big deal, but that small change helped me seem like I understood the game more while also showing my vulnerability and trust to those whom I asked beforehand.

The same went for our disc golf team. As it was our newest sport and one I knew the least about (plus, there is literally NO research on it), I peppered them with questions every time they came in for a lift. “What is a hyzer?” “When would you throw forehand versus backhand?” “How long are tournaments?” So many questions but so many good answers and discussions. My willingness to be vulnerable and learn from them has allowed for a better relationship between me and the athletes on the team as we learn and grow together (most have minimal weight training experience).

The last thing that I ask is in reference to my “learn the language” tip. As mentioned, every morning, I watch a video about one of our sports to get a better understanding of the language, movements, or tactics used in the sport.

Some examples to give you an idea are:

Later in the day, when that sport comes in, I fire off more questions in reference to what I watched to check if it is legit and see what more I can learn. “I was watching a video this morning on making headers, and it said you need to time your jump right so you can propel your head into the ball to direct it to where you want to go. How do you practice that?” Conversation started. Knowledge gained (plus they will love that you are trying to learn more about them).

4. Make Mistakes

The last point is almost like a summary of all these, as it ties them all together—don’t be afraid to fail, say the wrong thing, or make a fool of yourself. Yes, there are times when you will say the wrong phrase, explain things too “coachy,” or talk about the why behind an exercise and then have confused looks staring at you. But you know what? That is how you learn.

Taking a quick moment to ask an athlete if what you said was correct, if it made sense, or why people looked confused is what helps you learn and move on.

I am not saying I am perfect at this. I still make mistakes in my explanations with a sport every day (even hockey—after all, it was a while ago that I played). But by tripping over your words, trying to make sense of everything, athletes will see that you are trying and want to get better. Plus, by asking questions, they will see you truly do want to learn more and will help you learn just as you are helping them.

Lastly, be an observant coach. Listen to your athletes, watch the sport, and practice the skills if you have time. Trust me when I say it goes a long way in crafting a message that is not only physiologically correct but also resonates with your end user and helps them see the bigger picture (which will lead to better effort, better buy-in, and better results). Just like the nurses I encountered in the NICU, while you most likely studied the science and what to do to enhance your knowledge of your job, it is important not to forget who the end user is and who you are communicating with. After all, it doesn’t matter what you said, but what they heard!

Good luck!

Peace. Gains.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF