Sprinting is arguably the most central-nervous-system-intensive exercise that the human body can perform. As a consequence, there are many elements that go into performing a sprint with efficient form. So, I believe that coaches must take the time to seek out and try to learn from the best sprint coaches in the world if they are to properly understand how to program, diagnose, and alleviate issues associated with slow speeds, improper technique, or injury prevalence.

Where do strength and conditioning professionals learn to teach the basic barbell lifts like a squat, bench press, or deadlift? The smart ones draw from powerlifting, because no other discipline pays more attention these lifts. This is also true of incorporating Olympic weightlifting movements. Strength coaches will learn from Olympic weightlifting coaches, many of whom also hold certifications from organizations like USA Weightlifting.

In the weight room, it’s very dangerous to expose a player to high resistance loads with inefficient form, and the same holds true when exposing a player to high speeds on the field. In fact, many coaches are reluctant to have their players sprint beyond 10–15 meters for fear of hamstring injury. However, with proper programming and an understanding of sprint biomechanics, you will find that you can greatly reduce athlete risk and they will be able to attain the rewards of more speed, better elastic ability, and greater robustness.

One major issue I believe is sort of epidemic in team sports, leading players down the fast track to hamstring and hip problems, is “butt-kicking” or “kicking out the back.” Share on XIn this article, I want to talk about one major issue that I believe is a sort of epidemic in team sports—one leading players down the fast track to hamstring and hip problems. I call it the “butt-kicking epidemic,” also known as “kicking out the back.” This butt-kicking issue almost always occurs when athletes enter phases of maximum speed (where the body position becomes more upright). Upright sprinting mechanics have been written about extensively, yet still seem to elude many coaches working with team sport players.

My goals with this article are to:

- Present and discuss the butt-kicking problem.

- Show examples of athletes I’ve trained who have displayed this issue in differing forms and degrees.

- Discuss what I did to help alleviate the issue.

Breaking Down the Butt-Kicking Problem

As a starting point for understanding the butt-kicking issue, we can briefly discuss the gait of upright sprinting, which involves five major landmarks:

- Touch-Down: When the foot first touches the ground.

- Stance Phase: When the foot fully supports the player’s body weight, ending when the foot starts to leave the ground again.

- Toe-Off: When the foot is last in contact with the ground before swinging back to start another sprint cycle.

- Swing Phase: When the foot is no longer in contact with the ground and moves forward to prepare for another touch-down.

- Flight Phase: When neither foot is in contact with the ground, including the swing phase.

The butt-kicking problem occurs when a player exhibits one or more of the following:

- An overextended lower back (excessive arching) and/or an emphasized anterior pelvic tilt (duck butt position) heading into touch-down.

- Too much forward leaning throughout the entire sprint cycle.

- The heel striking far in front of the center of mass during the stance phase.

- The heel colliding into the buttocks far behind the center of mass during the swing phase.

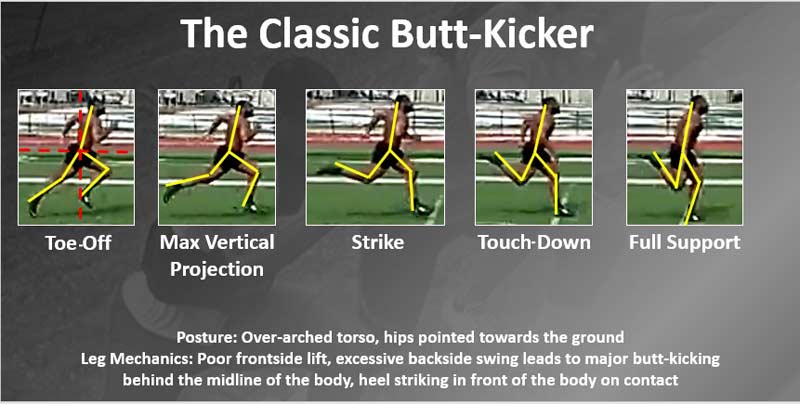

Video 1. This is one of my athletes exhibiting what I call the “classic butt-kicker issue,” where all these problems are on display.

You can easily bring one or more of these issues to light by using the ALTIS Kinogram Method, which simply relies on photographs to determine technical issues in sprint performance. The Kinogram Method can help coaches see different points of the sprint cycle to determine where certain problematic areas may or may not exist for each individual player. The kinogram typically observes five key landmarks for this purpose, each existing within the gait of a sprint cycle. For consistency, I will use ALTIS’ definitions of each landmark:

- Toe-Off: The last frame before the athlete’s support-leg foot is in contact with the ground.

- Maximum Vertical Projection (MVP): The maximal height of vertical projection, as defined by the position where both feet are parallel to the ground.

- Strike: Because of the relative difficulty in defining this position, ALTIS has determined that using the opposite leg is more efficient. They define the “strike” position as when the opposite thigh is perpendicular to the ground.

- Touch-Down: The first frame where the swing-leg foot strikes the ground.

- Full-Support: The frame where the foot is directly under the pelvis—the toe of the foot should be plumb vertical with the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) of the pelvis.

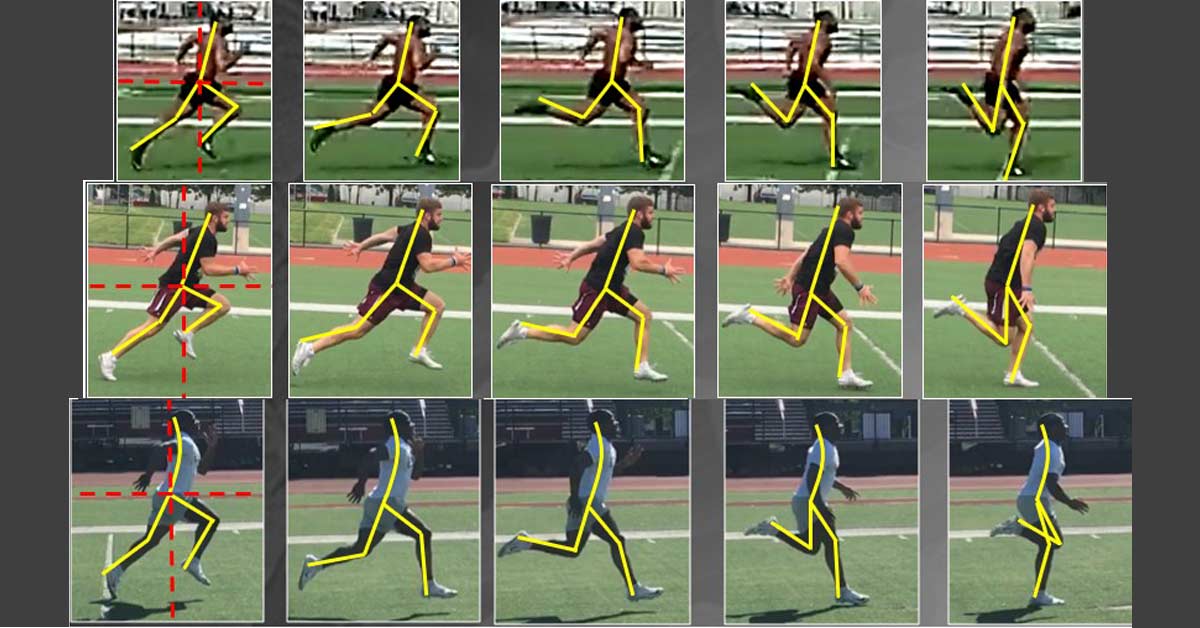

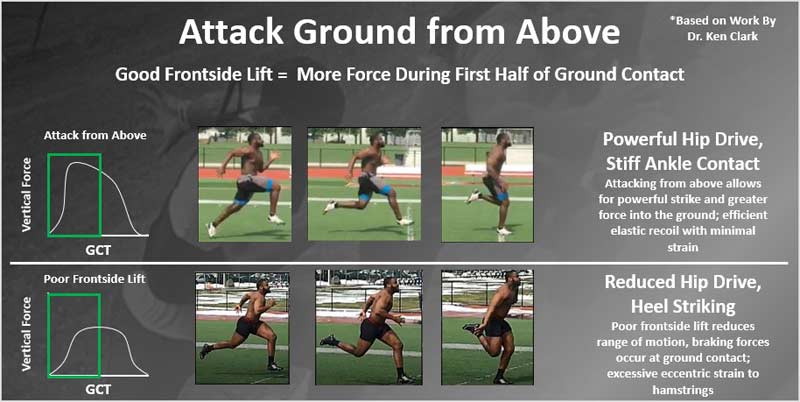

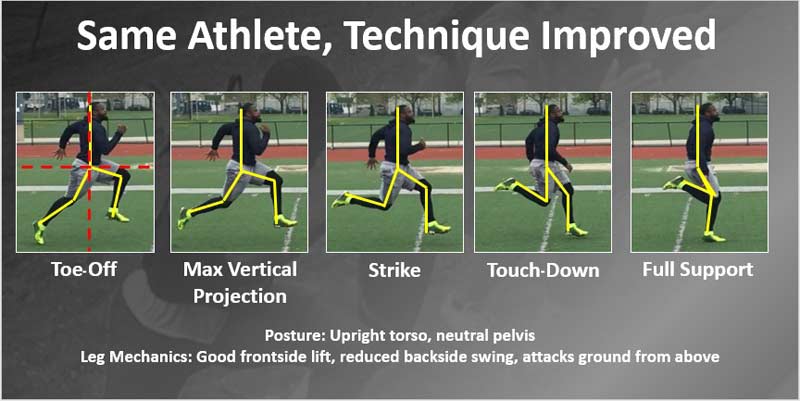

Given these definitions, let’s first observe a kinogram of one of my athletes. This athlete is a professional rugby forward who I believe shows safe, efficient sprinting technique:

The technical points I’ll discuss in this article are largely based on the work of Dr. Ken Clark, as well as educational principles from ALTIS. In the above kinogram, the rugby forward shows facets of good technique including:

- A nice upright torso, with a neutral pelvis.

- Good frontside lift of the lead leg, shown by how the knee punches toward the hip during toe-off.

- Not overextending with the trail leg at toe-off. As the kinogram sequence continues, we can thus observe that he drives the lower limb of the trail leg forward toward the lead leg in good sequence.

The Importance of Proper Frontside Lift

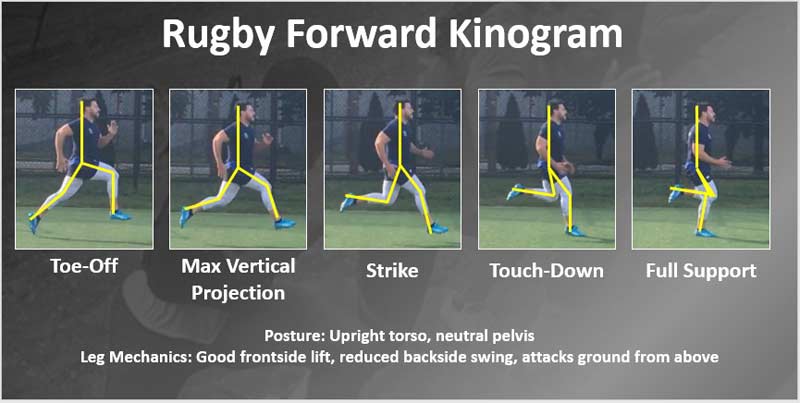

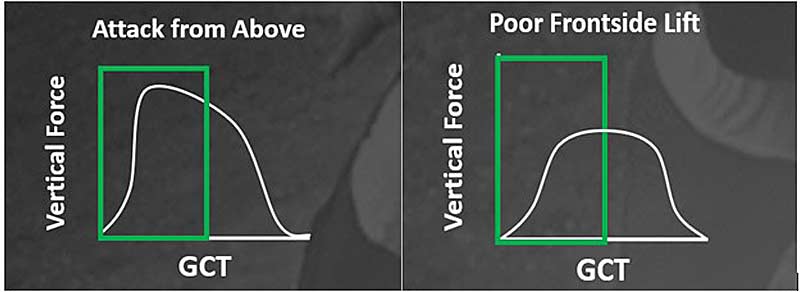

Good frontside lift allows the player to attack down into the ground from a greater range of motion, effectively applying greater force into the ground on initial contact. Ken Clark has presented research showing that efficient sprinters who attack from above are able to apply greater vertical force in the first half of ground contact, as opposed to sprinters with poor frontside lift. Image 2 below exemplifies this. While both sprinters will have similar force application in the second half of ground contact, the green box highlights how the initial impulse is much higher for the one who attacks from above.

Attacking from above tends to coincide with a powerful hip drive and stiff ankle contact, resulting in efficient elastic recoil with minimal strain on the hamstrings. Keeping the force application elastic at higher speeds helps spread the stress across more connective tissue, incorporating better use of the tendons and fascia with less localized trauma to the posterior chain. When performed properly, athletes look like they are bouncing down the runway rather than forcing their way.

Video 2. This is a clip of some of my athletes performing sprints with good frontside lift. (Yes, some other issues may be on display here, but for the purposes of this article, I am focusing on the butt-kicking problem).

In contrast, poor frontside lift reduces the available range of motion at the hip upon entering ground contact, so force will be lower. Additionally, the body posture will feature a pelvis rotated toward the ground (excessive anterior tilt) rather than a neutral position. This posture effectively puts greater eccentric strain on the hamstrings, causing them to absorb more force directly into the muscle, resulting in greater tissue trauma. Heel striking too far in front of the body as a result of this posture forces the hamstrings to operate first as a braking system and then as a propulsive system. Essentially, the hamstrings are being forced to help prevent the athlete from falling on their face, which means double the responsibility and a greater risk of damage.

Essentially, poor frontside lift forces the hamstrings to help prevent the athlete from falling on their face, which means double the responsibility and a greater risk of damage. Share on XImage 3 below shows two pictures of the same athlete performing upright sprinting—one picture in which he has poor frontside lift and another where he attains better posture to attack from above. The sequence associated with poor frontside lift represents the “butt-kicking” problem. To prevent confusion, it’s worth explaining that it’s not that the heel of the trail leg should never come near the buttocks. Rather, the problem occurs when the heel approaches the buttocks too far behind the center of mass, thus exemplifying an anteriorly rotated pelvis, reduced frontside lift, and excessive eccentric strain on the hamstrings.

It’s not that the heel of the trail leg should NEVER come near the buttocks. Rather, the problem occurs when the heel approaches the buttocks too far behind the center of mass. Share on X

Over the rest of this article, I’ll highlight three athletes who came to me with different archetypes of the butt-kicking issue, and I’ll discuss the strategies I used to help reinforce better technique. All three had long histories of hamstring tweak/strain problems. Upon enforcing some technical improvements, we were able to train consistently for several months in the off-season periods at very high speeds without any hamstring issues. I am certainly grateful for the mentors whose works I have studied to help educate me on this easily fixable technical issue.

1. The Classic Butt-Kicker

The Classic Butt-Kicker has all the problems associated with the butt-kicking epidemic. Their hips point toward the ground, they have excessive arching at their spine, their trail leg swings all over the place behind the body, and they do all they can to stay on their feet and not fall on their face. When coaches see this happening, they can pretty much guarantee that the player will eventually strain their hamstring.

With this player (an NFL linebacker), I realized I had to come up with a way to get him to understand good frontside lift. What I came up with is an exercise that I call the Medicine Ball Knee Punch Run. In this exercise, the player holds a light medicine ball (5–10 lbs.) in front of his torso, slightly above the navel. I then ask him to try and sprint forward while attempting to punch his knee toward the medicine ball so that the thigh contacts the ball.

As a quick side note, even if the thigh does not fully contact the medicine ball, the intent of the exercise can help the player understand what a good frontside lift feels like. Also, having the weighted ball in the front of the body allowed for him to automatically adopt a neutral pelvic position and activate his core.

Video 3. The first part of the clip shows the athlete performing the Medicine Ball Knee Punch Run exercise. The second part then shows him sprinting without the medicine ball. Notice how the player was able to maintain an upright torso, neutral pelvis, and good frontside lift in the subsequent sprint after being primed with the medicine ball drill.

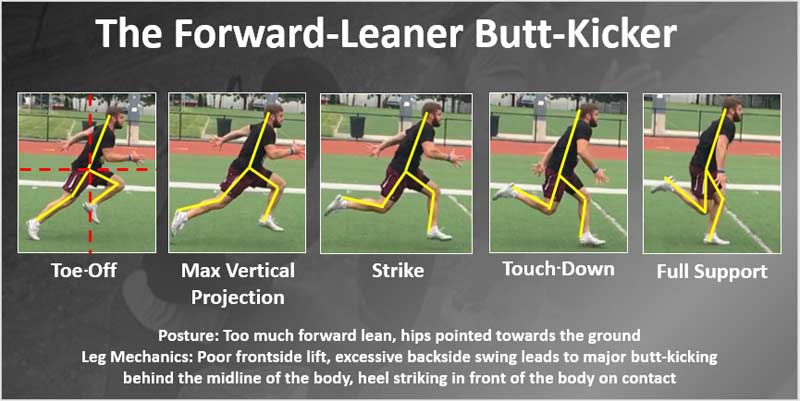

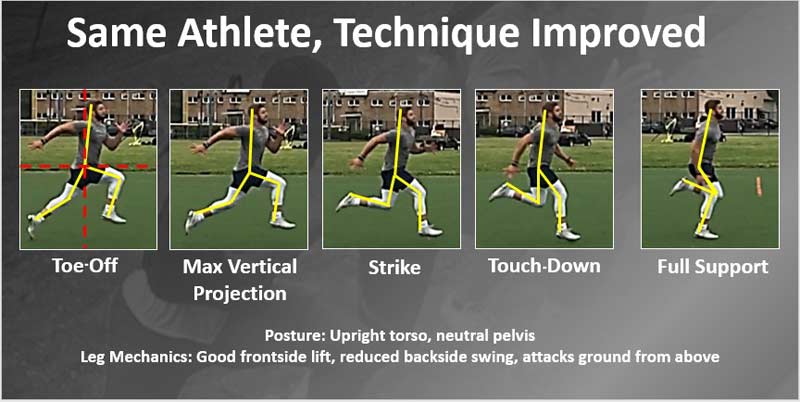

2. The Forward-Leaner Butt-Kicker

The Forward-Leaner Butt-Kicker is able to maintain a neutral posture in terms of the alignment between the spine and the pelvis but simply tilts too far forward, so the hips still point toward the ground at toe-off. This typically results in a player who tries too hard and leans their body weight toward the finish line rather than keep true to the technique of the maximum speed phase.

To help alleviate this issue, I reviewed three primary principles of acceleration from ALTIS:

- Projection: The body angle and force application of each step during acceleration, resulting in the displacement of the athlete across the ground. During early acceleration phases, force application is more horizontal in nature. With each subsequent step, the force application becomes more vertical until reaching top speed. With the butt-kicking problem, athletes attempt to apply horizontal force into the ground for too long, negatively affecting the rhythm and rise.

- Rhythm: The stride rate, which gradually gets faster as speed increases. Every step should be a little bit faster than the one before it. Stuart McMillan refers to the rhythm of acceleration as a crescendo, where the sound of each step during early acceleration is further apart, and the gap between the sound of foot contacts will get narrower as speed increases.

- Rise: The projection angle of the body will gradually rise with each step until the athlete is fully upright when approaching top speed. I like to use the analogy of a plane taking off. There is a smooth, gradual change in the angle of the plane as it starts to leave the ground. Likewise, when athletes sprint. As the speed output increases, the body angle should get progressively more upright with each step in a way that matches the optimal angle of projection and the rhythm of acceleration.

For this athlete, I assumed that he was struggling with the principle of rise. He just could not grasp the concept of allowing himself to sprint in an upright position. So, I presented him with a simple focal point. I told him to imagine that he is climbing a set of stairs that leads gradually into the horizon. I have never seen anyone run up a set of stairs with an excessive backside-swinging butt kick. Therefore, my hope was that he would contemplate this image and realize that no one will naturally run up a set of stairs without proper frontside lift.

Frontside Lift Coaching Cue #1 – Imagine You’re Climbing a Set of Stairs Gradually Leading Into the Horizon

It took this player a bit of time working with this cue to see improvement. I also used the Med Ball Knee Punch Run drill with him.

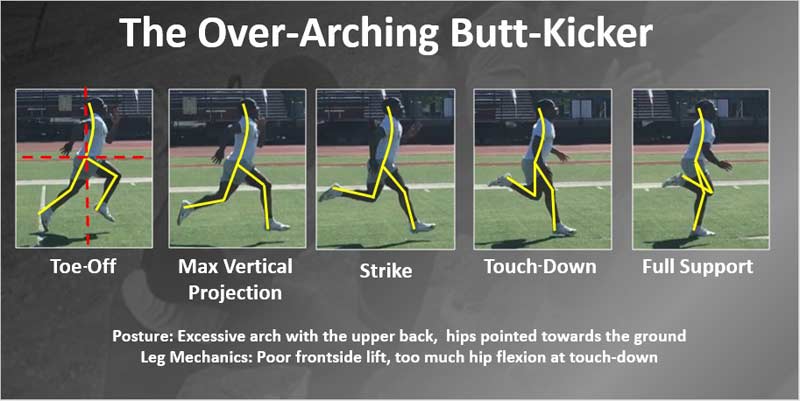

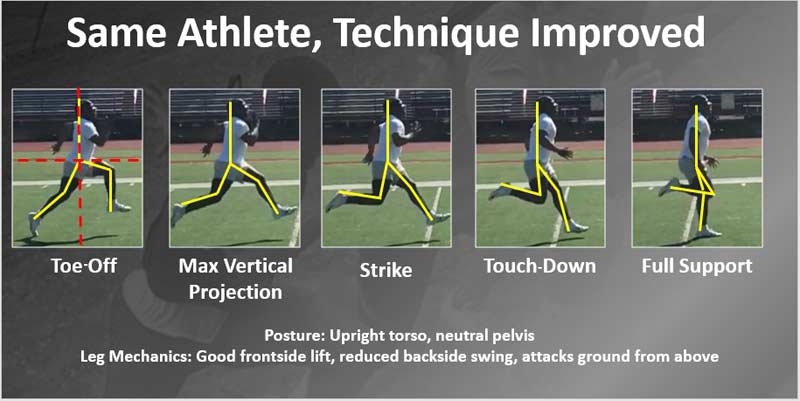

3. The Over-Arching Butt-Kicker

The Over-Arching Butt-Kicker has a unique form of the butt-kicking issue because the athlete is usually able to show nice bounce on ground contact and put decent vertical force into the ground. However, as seen in the kinogram below, frontside lift is limited because the athlete is simply overextending the spine, forming an excessive arch position. Therefore, the hips continue to point toward the ground rather than straight ahead, negatively affecting the elastic recoil on ground contact. In addition, the hamstrings still have to take on a substantial damaging load with this issue.

This particular athlete is a very reactive, explosive player, so I had to try and find a cue that would speak to him and get him to understand what I was looking for. The previous cue of climbing a set of stairs into the horizon was not working with him, so I quickly thought of attacking the same problem from a different perspective.

I realized that his excessive arching was due to him trying to force his way down the field, unnecessarily prolonging his ground contact times by thinking he was really propelling himself forward. But at top speed, we want fast ground contact times, and we want the athlete to really float across the field with great vertical force application on each step. So, I gave him a different cue.

Every athlete has a different brain, so coaches need to constantly look at how to educate them from various vantage points to solve problems. Share on XI told him to imagine he was sprinting over hot coals getting hotter and hotter; that he had to make it through to the finish but didn’t want to spend time on the ground because he’d burn his feet. This cue registered to him that it wasn’t just about fast feet; it was also about putting enough force into the ground to make it the whole way.

Frontside Lift Coaching Cue #2 – Imagine You’re Running Over Hot Coals Getting Hotter with Every Step

Amazingly, this cue worked immediately with him and the kinogram below shows his very next repetition. The over-arching disappeared, as he was able to focus on the “pop” in each step rather than straining to get to the finish line. While the first cue did nothing for him, the next cue helped instantly. Every athlete has a different brain, so coaches need to constantly look at how to educate them from various vantage points to solve problems. This athlete reminded me of that important lesson.

Thigh Separation as an Important Indicator

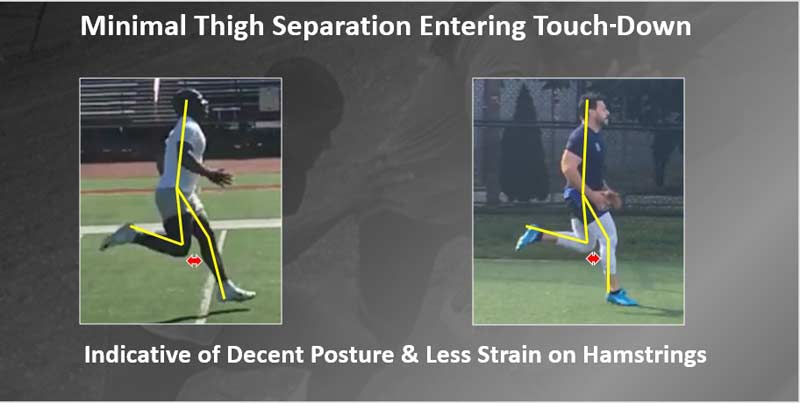

One of the lessons I learned from Dr. Ken Clark is that the touch-down phase of a kinogram provides a very clear indication of poor posture when sprinting at high speed. Image 10 below reveals how an excessive thigh separation heading into touch-down is a result of the butt-kicking issue. Vertical force application is poor, so the athletes are unable to effectively cycle their legs around, resulting in heel striking further in front of the center of mass and mayhem for the hamstrings.

In contrast, minimal thigh separation upon entering the touch-down phase indicates decent vertical force production, where the athletes are able to spend more time in flight and cycle the legs around, as shown in Image 11. These athletes are able to remain more elastic at ground contact, taking strain off of the hamstrings and spreading it more effectively across various connective tissues. Once I see improvements in thigh position at touch-down, I feel much better about introducing longer distances and higher speeds in my programming because I know the risk of hamstring injury has drastically subsided.

Save the Hamstrings

My hope is that the butt-kicking problem becomes common knowledge for coaches of any sport involving sprinting. The more that coaches are aware of the high-risk positions and then equipped with potential solutions to alleviate them, the safer all our athletes will be. That said, the butt-kicking problem is just one station along the railroad line of keeping players safe, but it’s my first stop when introducing athletes to any form of sprint training. I believe it’s really the most common issue with poor sprinting. In my experience, it’s everywhere. The exception is typically an athlete that has been exposed to a well-structured track and field program.

The more that coaches are aware of the high-risk positions leading to butt-kicking, and then equipped with potential solutions to alleviate them, the safer athletes will be. Share on XIt’s our duty as coaches to help our athletes learn how to sprint fast in the fastest and safest way possible. If we ignore safety, a high number of injuries will inevitably ensue. I don’t have social media anymore, but if I did, I’d tag this article with the hashtag #savethehamstrings. Let’s work together to end the butt-kicking epidemic and save the hamstrings.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Clark, K.P. Speed Science: “The Mechanics Underlying Linear Sprinting Performance.” PowerPoint Presentation.

Thanks for this priceless information!

Awesome information. If you don’t mind, would you be willing to share what program you utilized to draw the lines onthe picture slides? We create Kinograms, but would like to draw overlays on the pictures. Thank you.

Maybe Coaches Eye or Kinovea?

Very interesting article, go on learning and used in soccer players, addapted my oun methodology.

Excellent article with simple but apt verbal cues on the video.

Excellent article! Very informative and helpful!!

cues often won’t help because they presuppose the athlete to think.

Sprinting fast requires NO thinking. It’s all reflexes.

We have to feel the movements without any cues/thoughts.

This is where clearing the mind and being calm/relaxed comes from.

At the moment we try to force/think a high speed cyclic movement we are braking the cycle.