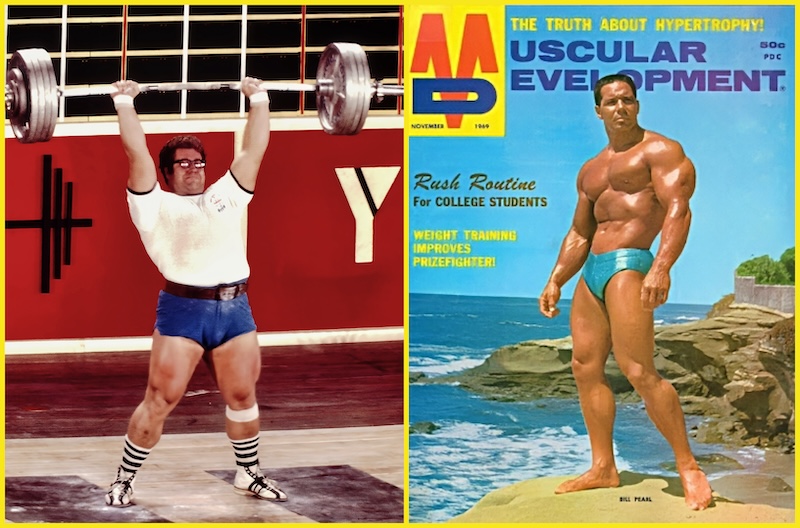

Before the age of professional strength coaches, considerable attention was devoted to overhead lifting. The standing press was contested in the Olympics, and many competitive bodybuilders hoisted impressive poundages in overhead pressing exercises, making them as strong as they looked. That was then—this is now.

Except in endurance sports such as cross-country and high-skill games such as golf, the bench press has become the go-to upper body strength exercise for athletes. There is no doubt the bench press will pack on slabs of muscle and strengthen the chest, shoulders, and triceps. What is puzzling is why an exercise performed while lying on your back has replaced standing overhead movements, especially dynamic ones such as split jerks and push jerks.

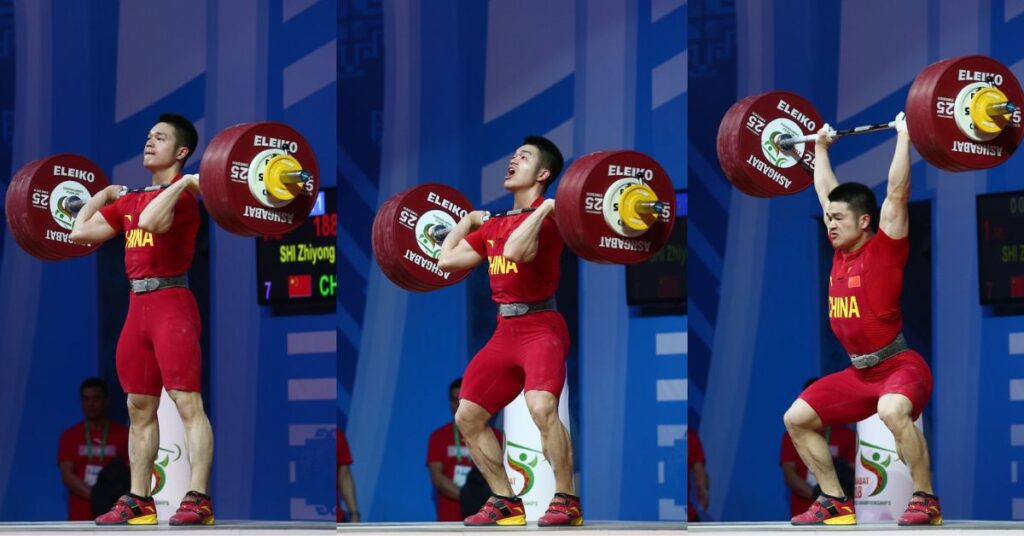

(Lead photo by Tim Scott, LiftingLife.com)

What is puzzling is why an exercise performed while lying on your back has replaced standing overhead movements, especially dynamic ones such as split jerks and push jerks. Share on X

Perhaps there are peer-reviewed studies proving the benefits of the bench press for developing athletic superiority. Perhaps, as popular strength coach and internet influencer Mark Rippetoe suggests, many strength coaches are too lazy to teach overhead movements. Or maybe, to present a moderately outrageous opinion, perhaps the reason the bench press gets so much attention is due to “gang culture,” a social phenomenon where everyone follows what everyone else is doing without considering the consequences.

Let’s get to the bottom of this!

The Bench Press De-Evolution

About 30 years ago, the strength coach of a D1 college football powerhouse told me he only had one player on his team who bench-pressed 400 pounds in high school. Now, a 400-pound bench is commonplace among five-star high school recruits, along with 500-pound benchers in college. To reach these levels, considerable time must be devoted to bench pressing, at the expense of other athletic fitness qualities. Again, the question is, “Why?”

I sought to answer this question when I was a strength coach for the Air Force Academy football team in the ’80s and ’90s. I compared three years of data on our core lifts to the top three rankings for each position on the depth chart. I found no significant correlation between the bench press and playing ability for the “skill” players, such as quarterbacks and cornerbacks. The bench press correlation was higher for linemen, but not by much. The Falcons were a running team; our guards and tackles needed exceptional lateral quickness to pull, so we favored agility and explosiveness over brute strength.

The NFL Combine doesn’t test 1-rep maxes but rather max reps with 225 pounds. Stephen Paea played for four NFL teams and holds the official record with 49 reps, although undrafted Justin Ernest did 51. Impressive, but the number of reps changes the test from measuring absolute strength to muscular endurance. From a sports-specificity perspective, this makes no sense to me.

The average play in the NFL is about four seconds, which translates into a work:rest ratio of 1:10. Further, one peer-reviewed study examined the results of 1,155 athletes who participated in the NFL Combine between 2005 and 2009. The researchers concluded: “Using correlation analysis, we find no consistent statistical relationship between combine tests and professional football performance, with the notable exception of sprint tests for running backs.”

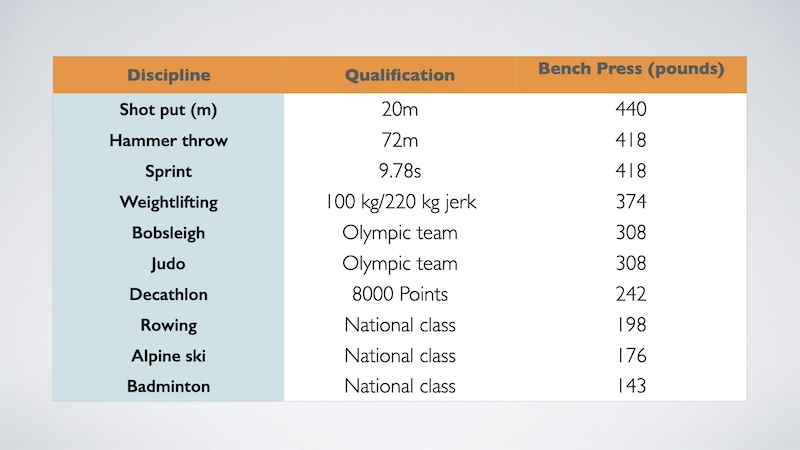

Expanding to other sports, about 30 years ago, Canadian strength coach Charles Poliquin shared with me the following table comparing the bench press results for elite male athletes in various sports. These athletes competed in the ’80s, and among them were World and Olympic champions. For several sports, bench press results were unremarkable. (Of course, the chart is a bit misleading, as the sprinter referenced was Ben Johnson, whose strength results were the exception and, as far as I know, never equaled.)

Regarding the throwing events, the incline press may be a better predictor lift for the upper body. Estimates vary, but the optimal release angles for these events are 45 degrees for the hammer, 37–39 degrees for the shot, and 35–44 degrees for the discus. According to strength coach Bill Starr, author of one of the most popular books on athletic fitness training, The Strongest Shall Survive, many throwers achieved exceptional results in the incline bench press.

At this point, a better question is not if the bench press has value in athletics but if overemphasizing the lift does more harm than good. Share on XStarr said many track and field throwing legends, including world record holders Parry O’Brien, Dallas Long, Randy Matson (shot put), Al Oerter (discus), and Harold Connolly (hammer), “handled well over 400 pounds on the incline.” Al Feuerbach was a world record holder in the shot put, and I talked to him briefly back in the ’80s. He said the dumbbell incline press was the best upper-body exercise for the shot put. This makes sense, not just because of the release angle of the shot but because you put the shot with one arm.

At this point, a better question is not if the bench press has value in athletics but if overemphasizing the lift does more harm than good.

A Balance of Power

Giving credit where it’s due, it was Bill Starr who first got me questioning the value of the bench press. “What most people don’t recall is that before the bench press became the primary upper-body exercise, there were few, if any, rotator cuff injuries. That’s because the overhead press, which was at one time the main upper-body movement, actually helps to strengthen the area known as the rotator cuff, mostly by having you support heavy weights overhead.” Starr was on to something.

One meta-analysis found that 36% of documented injuries and disorders associated with resistance training involved the shoulder. The researchers concluded that one of the primary risk factors for shoulder injuries was flexibility restrictions, particularly with internal rotation of the shoulder. Expanding on this topic, physical therapist Brian Schiff pointed out these five concerns he had with excessive focus on the bench press:

- Poor posture via rounded shoulders and increased internal rotation caused by pec tightness.

- Repetitive friction between the rotator cuff and labrum, particularly in a deeper range of motion.

- Acquired capsular laxity in the anterior shoulder joint over time.

- Arthritis in the acromioclavicular joint (known as weightlifter’s shoulder).

- Risk of pectorals major rupture.

Regarding flexibility issues, this is usually not an issue with weightlifters due to the large amplitude of the competition lifts (snatch, clean and jerk). I can’t say the same for those who only practice partial lifts, the so-called “weightlifting derivatives.”

There is also the inherent high-risk nature of the bench press, particularly when it’s not performed inside a power rack or with an “attentive” spotter—note the quotation marks around the word “attentive.” On this topic, the Consumer Product Safety Commission in the U.S. said that 3,820 injuries were sustained in connection with the bench press in 2002. The breakdown had 53% of the injuries to the face or neck and 42% to the chest. Several deaths were also reported.

Elite bodybuilders perform the bench press but apparently do not emphasize it as much as you might think because it’s not a full-range exercise. I’ve worked for many popular newsstand bodybuilding magazines, including Flex and Iron Man, and the consensus among pro bodybuilders appears to be that dumbbells are better for overall chest development.

Dumbbells permit the arms to come together at the top of the movement, allowing for a longer range of motion of the pectorals. I’ve also seen a recurring theme with top bodybuilders that it’s essential to hit the muscles from all angles with a variety of exercises for more balanced development.

I’ll let Coach Poliquin have the final word on this subject, citing a conversation I had with him 30 years ago. “Eighty percent of your presses should be performed from different angles, such as with an incline or military press. Further, at least 50 percent of pressing exercises should be performed with dumbbells, as they offer a more natural movement pattern and provide a more challenging workout for the muscles that stabilize the shoulder.”

The Overhead Solution

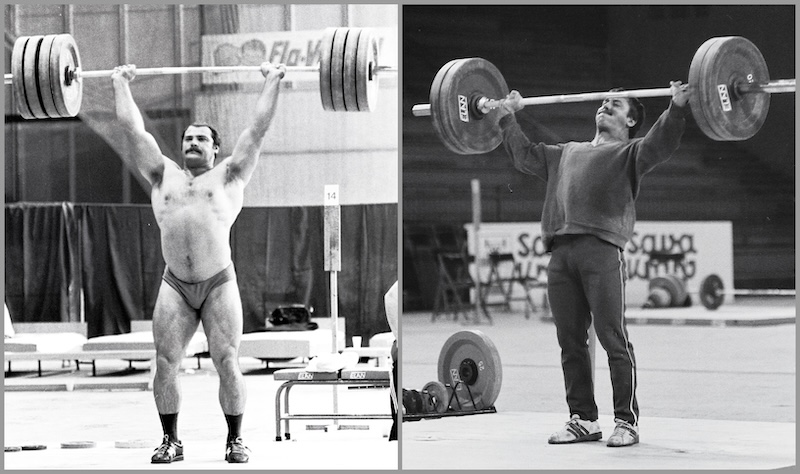

The overhead movements have always been a mainstay of the training for throwers in track and field (well, except for javelin throwers—I have yet to make sense of their workouts). Two shot putters who also excelled in weightlifting were Al Feuerbach and Brian Oldfield.

Feuerbach is a three-time Olympian who broke the world record in the shot put in 1973 with a put of 71-7. Feuerbach also excelled in overhead lifting. His best official lifts were 341 pounds in the snatch and 418 in the clean and jerk, which won him the 242-pound bodyweight division in the 1974 Senior National Weightlifting Championships.

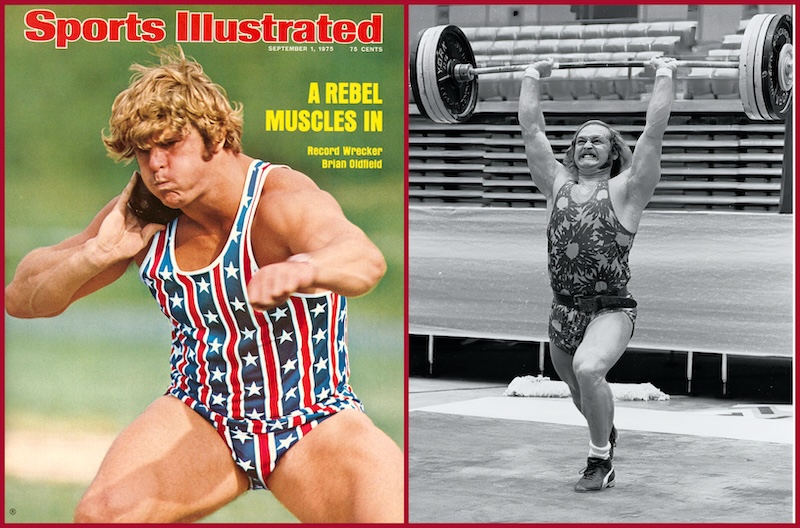

Oldfield was a 1976 Olympian in the shot put who appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated. Oldfield broke one official world record (72 feet 6 ½ inches) and two unofficial ones, with a best result of 75 feet. In 1976, he appeared in a unique televised competition called Superstars that pitted the world’s best athletes against each other in events other than theirs.

One event was weightlifting, where athletes removed a weight from squat stands and had to thrust it overhead to extended arms. In the preliminary competition, Oldfield broke the Superstars record with 300 pounds, which was so easy that he did it for five reps. In the finals, he faced Lou “The Incredible Hulk” Ferrigno, a 6’5” bodybuilder whose body weight often exceeded 300 pounds in the off-season.

Ferrigno lifted 290 pounds using an (extremely awkward) split jerk technique, missing 310, whereas Oldfield made that same weight easily for another record and called it a day. It’s not surprising. A photo of Oldfield appeared in Strength and Health magazine in 1973, clean and jerking 350 pounds, and he reportedly lifted considerably more overhead from squat stands in training.

I contend that the bench press should be de-emphasized in athletic training and complemented by dynamic overhead movements, particularly the push jerk. I would only recommend the split jerk (as performed in weightlifting competitions) if taught by a qualified weightlifting coach, not just a strength coach who passed a weekend certification. And with good reason.

I contend that the bench press should be de-emphasized in athletic training and complemented by dynamic overhead movements, particularly the push jerk. Share on XThe split jerk is arguably the most technical part of weightlifting and the most missed portion of the lifts in competition. Attend a weightlifting competition at any level, and you’ll see that it’s rare for an athlete to miss a clean. This is despite less power being needed to jerk a weight than to clean it—but don’t take my word for it.

In researching this topic at the elite level, weightlifting sports scientist Bud Charniga looked at the success/failure rate for the snatch and clean and jerk at 16 major international competitions, including the Olympic Games. He found the success rate for final attempts in the clean and jerk ranged from 23% to 46%. “Consequently, it is reasonable for a coach or athlete, in the midst of the heat of competition, to assume that at least 60% of the 3rd attempt jerk weights selected will be failures; it is even a fair bet to assume as many as 70% will fail.”

A Balance of Power

The squat jerk is another form of jerking. Rather than splitting the legs after thrusting the bar overhead, the athlete descends into a full squat. Generally, the athlete catches the bar in a half squat and rides it down into a full squat before rising (image 4).

Besides requiring exceptional flexibility, the squat jerk is a far more complex lift, as the narrower base of support and the deep squat position associated with this technique offer a small margin of error (video 1). However, world records have been broken with the squat jerk, usually by Asian lifters (who often have a lower center of gravity and are thus more stable in a low squat).

Video 1. Two high-level weightlifters performed the squat jerk to show the lift from the front and the side, and one performed the split jerk. The male athlete, coached by the author, is shown split-jerking double body weight. (Snethen video courtesy Heather Snethen, Snethen photo by Bruce Klemens.)

A push jerk (also called a power jerk) is a better option. The push jerk involves a powerful leg drive with the arms and shoulders being used to push the body under the bar aggressively. Rather than splitting the legs forward and backward, they move laterally while bending slightly to receive the weight. This action is more associated with the movements involved in dynamic sports. Let me expand on this comment.

The push jerk involves a countermovement sequence found in sports: fast eccentric/brief isometric/fast concentric—this is followed by a second eccentric contraction when the lifter drives their body under the bar. During the upright sprint phase, the knee bends quickly after the swing phase when the front foot touches the ground (fast eccentric); there is minimal ground contact time (brief isometric), followed by a rapid strengthening of the leg (fast concentric).

For most weightlifters, less weight can be lifted with the push jerk than with a split jerk (if the trainee is well-coached). One reason is that the bar does not have to be raised as high, and the split landing produces more upward force on the bar. However, impressive lifts have been performed in this style.

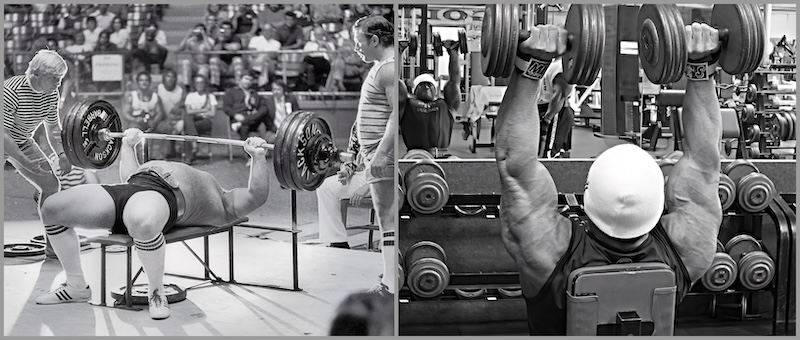

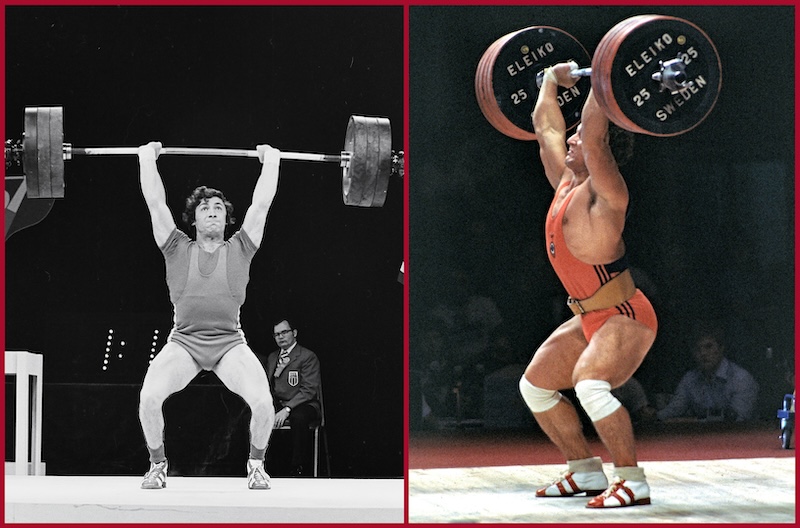

Shown in image 5 are two of the best push jerkers in the history of weightlifting, Yurik Yardanyan and Viktor Sots. Yardanyan was an Olympic champion and push jerked 485 pounds at a body weight of 181 pounds, taking the bar from stands. Viktor Sots was a World Champion who reportedly push jerked 589 pounds at 220 pounds body weight, also taking the bar from stands, and made two clean and jerk world records using the split jerk. (Fun fact: Sots reportedly military pressed 413 pounds from a full squat position!)

What about the push press, or a variation called the muscle snatch that is performed with a snatch (wide) grip? Yes, these lifts check off several boxes for athletic fitness training, being performed from a standing position and involving a countermovement of the legs that incorporates the elastic properties of the tissues. However, the problem is that the push jerk is an extension in one direction—there is no rebending of the legs after the athlete drives the bar.

“A weightlifter learns to consciously straighten the legs fully to execute the push press,” says Charniga. “This is an incorrect habit because a weightlifter should have begun switching directions from lifting to descending while the knees are still flexed. There is no instantaneous switching of directions from lifting to descending in the push press. Consequently, the arms and shoulders “press” the barbell up with the assistance of the leg drive instead of pushing the trunk away from the barbell.” The result is that the arms extend slower, and less weight can be lifted.

Charniga says these technical differences adversely affected the performance of the competition jerk, and for this reason, “the push jerk became a popular assistance exercise.” It also suggests that the push press is more of a bodybuilding/general strength exercise rather than an explosive exercise such as the push jerk. (I would add that the muscle-building effect of a push press can be enhanced by attempting to lower the bar to the shoulders slowly, increasing the mechanical tension on the arms and shoulders.)

Although the shoulders and triceps are used in the push jerk, it should be considered more of a dynamic leg exercise, like a vertical jump. When I was 17, I jerked 335 pounds overhead from stands in front and jerked 330 pounds behind the neck. The same day I lifted 335, I missed a 205-pound bench press. One more story.

Although the shoulders and triceps are used in the push jerk, it should be considered more of a dynamic leg exercise, like a vertical jump. Share on XIn 1979, on the flight home from the Senior National Weightlifting Championships, I sat next to the winner of the 148-pound bodyweight division, David Jones. He told me that he severely injured a pectoral muscle the week before the competition, which suggests that pectoral strength, and, indirectly, bench-pressing ability, has little relevance to weightlifting.

One weightlifting coach who often has his athletes push jerk rather than split or squat jerk is Ciro Ibañez. Taking the bar from squat stands, his 16-year-old son Brayan push jerked 451 pounds at a body weight of 176 pounds, and his 12-year-old daughter Emily push jerked 264 pounds at 121 pounds body weight. I should mention that his daughter is coached by Coach Ibañez’s wife, Abigail Guerrero. They are shown in video 2 lifting in competitions using the push jerk style.

Video 2. Emily Ibañez Guerrero is shown clean and push jerking 242 pounds at 130 pounds body weight, and her brother Brayan is shown clean and push jerking 368 pounds at 176 pounds body weight. Emily was 12 at the time, and Brayan was 16.

In track and field, I’ve found that many coaches do not want their sprinters and jumpers to perform any exercises from the floor to keep their legs fresh—I beg to differ, but it is what it is. Many are also not open to having their athletes use lighter weights through a full range of motion. So, instead of power cleans, they will have their athletes perform hang power cleans or power cleans from boxes. Because the range of motion of the legs is small and these lifts are explosive, the push jerk should be an easier sell for the strength coaches who work with track athletes.

Because the range of motion of the legs is small and these lifts are explosive, the push jerk should be an easier sell for the strength coaches who work with track athletes. Share on XOne final advantage of the push jerk is that it is relatively safe, especially compared to the bench press. If you miss the weight, you drop it. However, consider that you may miss a weight behind. For this reason, a strength coach should teach their athlete how to miss a push jerk safely (basically, “open your hands and step forward as fast as humanly possible!”).

The number of exercises an athlete can do to improve their athletic ability is seemingly endless, but careful consideration must be taken to find the best ones for their sport. The bench press is here to stay, but the push jerk should be one exercise to consider adding to any strength training toolbox.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Rippetoe, Mark. Personal Communication, February 3, 2024.

Weis, Dennis B. “Bill Pearl’s Training Strategies.” Dennisbweis.com. ND

Fragoza, James. “NFL Combine Records: 40 Times, Bench Press, Vertical Jump, and More.” Profootballnetwork.com. March 3, 2023.

Biderman, David. “11 Minutes of Action.” The Wall Street Journal. January 15, 2010.

Letzlter & Letzlter (1986), modified by Poliquin, Charles (1986). RE: Strength levels of elite athletes.

Poliquin, Charles. Personal Communication, 1992.

Kumitz, Frank E. and Adams, Arthur J. “The NFL Combine: Does It Predict Performance in the National Football League.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2008;22(6):1721–1727.

Starr, Bill. “Powerful Shoulders & Chest Without Bench Presses.” (1993 version available on ditillo2.blogspot)

Starr, Bill. “Stabilizing the Shoulder Girdle.” Billstarrarticles.wordpress.com. January 11, 2016 (reprint, original publishing date unknown).

Kolber MJ, Beekhuizen KS, Cheng M-S S, and Hellman MA. “Shoulder injuries attributed to resistance training: a brief review.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2010;24(6):1696–1704.

Schiff, Brian. “Is Bench Press Bad for My Shoulders?” Raleigh Orthopaedic Performance Center, apcraleigh.com. November 29, 2021.

Stevenson, T. “Denial of Petition Requesting Labeling of Weightlifting Bench Press Benches to Reduce or Prevent Deaths Due to Asphyxia/Anoxia” (Petition no. CP 03-3) [Letter]; United States Consumer Product Safety Commission: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004.

Davis, Dave. “Move Over World…Here Comes Brian Oldfield.” Strength and Health. May 1973.

Charniga, Andrew, Jr. “Power, Equilibrium and the Struggle with Horizontal Gravity,” Sportinvypress.com. July 11, 2020.

Charniga, Andrew, Jr. “More About the Jerk,” Sportinvypress.com. April 29, 2014 (reprint from 2005).

Ibañez, Ciro, Personal Communication, December 2023.