[mashshare]

The sports performance industry often highlights the “process,” but when it comes down to it, outcomes are what matters. Given this reality, competition preparation becomes a vital component of the work we do as coaches and therapists.

One aspect of the training process that blends directly into the outcome of a competition is the pre-meet session. The importance of an established, well-thought-out pre-meet session should not be forgotten and serves as the main topic of this article, through both a health and a performance lens.

Key Considerations When Designing a Pre-Meet Session

The pre-meet session is the last session completed before a competition. It’s a dress rehearsal of sorts before walking out onto the big stage. The overarching objective is to ensure the athlete is prepared for the upcoming performance, both mentally and physically.

A pre-meet session is the time to motivate athletes through success, not to give excessive critique or make changes. Share on XFrom a psychological standpoint, confidence is key. Athletes should walk away from these sessions feeling comfortable with, and confident in, their ability to execute. It’s not a time to excessively critique or to make many changes. It’s not a time for learning through failure but rather a time to find motivation in success.

Physically, we must manage fatigue to ensure the athlete enters the competition in an appropriate state of readiness. These sessions should not overload the athlete to the point of compromising their upcoming performance. At the same time, they must contain the appropriate amount of stimulus to ensure the athlete does not enter the competition in a deep parasympathetic state.

How the Pre-Meet Session Fits into the Training Program

The pre-meet is often somewhat unscripted ahead of time since it’s impossible to predict how an athlete will present each day leading up to competition. Therefore, a daily assessment is required to collect the relevant information before filling in the details of the session. Also, with competent athletes who have a decent training age, the session’s final decisions often come through conversation with them on that day.

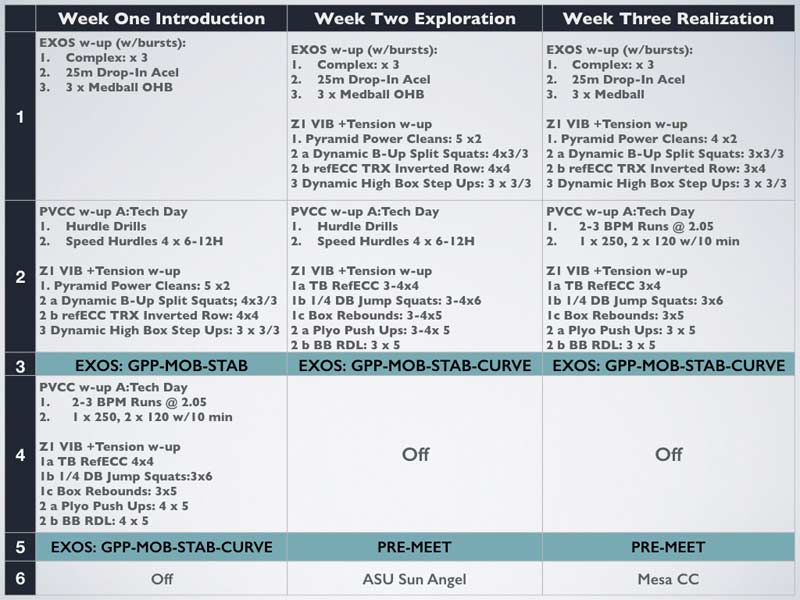

The table below shows where the pre-meet session fits within a training plan.

As you can see, each week begins with an acceleration-themed session. In weeks two and three, this session includes resisted accelerations with the 1080 Sprint and is followed by Zone 1, or Dynamic Effort, work in the weight room.

With competitions slotted on the Saturday of both weeks two and three, Tuesday becomes the biggest training day of these weeks. We generally use them for technical development and refinement. However, in week three, the Tuesday focus shifts to speed endurance to alleviate some hurdling density with the training sessions, pre-meets, and competitions. We couple the Tuesday session with another Zone 1 session in the weight room.

As you can see, there’s a reduction in working sets for many exercises during the last week of the cycle—this is to help keep the athletes fresh for the final race. Although a one-set reduction doesn’t seem like much, on the whole, the athletes potentially are doing up to seven fewer sets across all exercises than the previous week.

From here—particularly during competition weeks—the next few days are all about getting ready to perform on Saturday. We generally execute our pre-meet two days out and take the day before off (or do a light warm-up). Or, in this case, we rest two days out and do our pre-meet the day before. It’s worth experimenting to identify which pre-meet strategy works best for each athlete.

Some athletes do better with a pre-meet the day before a competition while others do better with a pre-meet two days out and resting the day before. Share on XFor example, a standard hurdle pre-meet usually consists of some hurdle drills, followed by a few short, explosive technical reps: 2-3 x hurdle starts over 2-4 hurdles. This allows for a final rehashing of any particular concept and serves as a system check for the athlete as well. We want to ensure that everyone feels great the day before a race. If they don’t, we have some time to intervene when necessary. This standard template serves as the baseline for improvisation should an athlete need to deviate and do a different pre-meet session.

As mentioned, the pre-meet session is a vital component of competition preparation. The goal is to work toward a final polish on technical aspects and pattern execution, to perform a systems check on how the body feels, and to leave the athlete with a sense of confidence and preparedness for the upcoming meet. Overall, the session should be crisp, focused, and to the point.

Experiment to Determine What Works

Much of our training prescription is experimental in nature. In the fall, we use our Monday potentiation training sessions to get a glimpse of what works well, and not so well, for each athlete. Our goal is often simply to get them ready for a great Tuesday workout, which tends to be our most intense session of the week.

The content of the Monday session can vary significantly from athlete to athlete. Elements could include one, or a combination of, the following:

- Extensive warm-up

- Accelerations, block starts

- 2-3 x runs off the turn

- Tempo runs

- Drill work

- Rhythm work

- Plyometrics and throws

Once we know what works well for an individual athlete from Monday to Tuesday, we can use the same (or similar) elements as part of their pre-comp strategy and routine. Ideally, coaches should look to organize athletes into a few pre-meet groups, so they do the workout together.

In the winter, we take our established elements and use the indoor racing schedule to experiment with pre-meets one or two days out from the competition. Some athletes do better with a pre-meet the day before, while others do better with pre-meeting two days out and resting the day before. We experiment indoors to discover what works best for each athlete as arousal levels begin to increase during the competition period.

Other simple considerations for content and timing of pre-meet include:

- Health of the athlete

- Local vs. away meet

- Time of day for individual event

- Density of competition schedule

- Number of events in the meet

- Travel schedule to the meet

- Facility and equipment availability

Potentiation and the Pre-Meet

As a prime example of potentiation, local meets give us the chance to use tools such as the 1080 Sprint.

As you can see in the graph, during the second half of the session—when working back down the resistance ladder—there are greater peak speeds reached at the 20m mark. The most notable examples come from the first and last rep, which had the lowest resistance possible to collect data. These runs recorded peak speeds of 8.75 m/s and 9.21 m/s.

One application of this information to the pre-meet sessions is a reduced volume with the prescription of the following ladder:

- 1x20m unresisted

- 1x20m at about 25% body weight resistance

- 1x20m at about 50% body weight resistance

- 1x20m at about 25% body weight resistance

- 1x20m unresisted

Additionally, local meets allow us to take advantage of continuity in training. Just be warned, when traveling for competition, you must be aware of logistical considerations and facility access so you can plan accordingly. These times of potential scarcity lead to creative problem-solving and can be a very fun part of the job!

Through the processes of destructive deduction and creative induction, we can break down the elements that benefit competition preparation and creatively target these elements through different means.

No access to a 1080 sprint machine? Find a hill to sprint up or accelerate into the wind.

No barbell or weight room access? Devise a medicine ball routine or plyometric series you can use instead.

Screening and Performance Therapy

In addition to everything already mentioned, the therapist’s role during times of competition is as equally important as the coach’s role. Just as we use a trial and error approach during the early stages of training to determine which sessions and which elements elicit the desired results, the therapist must go through a similar process.

Since we can’t predict individual response to various inputs and interventions accurately, we must establish a close surveillance and monitoring system due to the complexity involved in the process. In the ALTIS Performance Therapy Course, our Senior Sports Medicine Advisor, Dr. Gerry Ramogida, shared a story on this topic involving Canadian sprinter Tyler Christopher, who was coached by Kevin Tyler:

Tyler Christopher came to us with a long history of hamstring strains. A combination of technical errors and overtraining appeared to be the common factors historically to his injuries.

In 2005, Tyler was ranked in the top two in the world in the 400m. He had repeatedly posted personal best times throughout the season and was undefeated coming into the 2005 IAAF World Championships in Helsinki, Finland. He negotiated the rounds well, having finished first in his heat and semifinal round setting up a meeting with the world ranked number one, and also undefeated athlete from that season, Jeremy Wariner.

The Living Movement Screen (LMS), the continued observation of movement across various thresholds of effort, is a key component of the ALTIS Performance Therapy Methodology. When these movements venture outside of an athlete’s typical expression, a conversation between the coach, therapist, and, at times, athlete occurs to determine the appropriate intervention, if any.

Dr. Ramogida recalls:

In the warm up to the final, things were progressing well. Tyler had felt good throughout the build up to the Championships and we had undertaken all of our usual recovery strategies throughout the competition in the build up to the final.

However, as we came closer to the call time, Tyler complained of right-sided hamstring tightness. My initial reaction was of some slight panic. Given Tyler’s history and having managed his return from a few of his previous injuries, alarm bells were sounding for me. We walked to the table. In our observations of his movement through the warm up to that point, including some build up runs and accelerations, he looked good.

From standing evaluation, his pelvic alignment looked good, and his SI joints were moving appropriately. On the table, his mobility was ok and his strength was also within normal limits for him, yet he felt “tightness” in his hamstring. Was there some underlying issue within the deeper fibers of his biceps femoris (where his injuries had repeatedly occurred)? Did he not hydrate well enough? Was the arousal of his first World Championship Final causing some increased awareness? The answer was I didn’t know, nor could I answer, “Why?”

What happened next is all too often out of the ordinary. In most cases, a therapist’s instinct is to remedy an athlete’s complaint. They take on the responsibility to fix the issue—which usually equates to taking action:

With Coach Kevin also observing, I suggested we do nothing and he agreed. Tyler, to his credit, despite the fact that he was heading into what at that time was the biggest race of his life, also, was fine with the decision.

I always tell therapists when teaching, ‘If you can’t answer the why for an intervention, then don’t do it.’ You have no certainty to the impact of your input if you do not have a rational reason for it, and simply because the symptom is there is not always good enough (given context). Tyler completed his warm-up and continued to notice his hamstring.

With this, Tyler still managed to compete well and come away with the Bronze medal. As coaches and therapists, we must strongly consider the actions we take or don’t take. Health and performance underpin everything we do, and the two are closely linked.

Closing Thoughts

The pre-meet session serves as the final technical and mental installation opportunity for elements the athlete is looking to execute in competition. This way, only a short reminder during the competition should be needed.

Likewise, the last few encounters with the therapy staff must be carefully thought out and reflective of the context of the situation. New inputs and interventions should be avoided to ensure continuity and confidence—and sometimes, nothing is better than anything.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

Jason Hettler is the Lead Strength & Power Coach at ALTIS. He holds his BSc. Exercise Science from Grand Valley State University and plans to complete his candidacy for a Masters of Science degree, with a focus on Sports Science, through Edith Cowan University. His previous experience includes work within the Olympic Strength & Conditioning department at Western Michigan University. Join the conversation with Jason via Twitter (@jhettler24) or his website Hettler Performance.

Jason Hettler is the Lead Strength & Power Coach at ALTIS. He holds his BSc. Exercise Science from Grand Valley State University and plans to complete his candidacy for a Masters of Science degree, with a focus on Sports Science, through Edith Cowan University. His previous experience includes work within the Olympic Strength & Conditioning department at Western Michigan University. Join the conversation with Jason via Twitter (@jhettler24) or his website Hettler Performance.