For me, in-season training has always been a double-edged sword. We walk a fine line between providing enough of a stimulus to continue making improvements in the speed-strength and power aspects of the force-velocity curve while keeping the volume-load low enough to keep the athletes fresh for competing at a high level. Since our athletes usually have heard that in-season lifting is a maintenance program, it does take them a while to come around to the idea of getting positive work done in the gym during the season.

We keep pushing the athletes during their competitive season because I believe in momentum—not just the measurable version of momentum from physics, but the immeasurable version of cognitive momentum. While cognitive momentum is not easily measured, it is easily seen during a game.

We see cognitive momentum all the time in games when it looks like one team can’t do anything wrong, and the other team can’t do anything right. Without momentum, even when the play calls are correct, someone either is physically out of position or mentally makes a mistake. Either way, the play is broken and not performed correctly. Or the call is correct, and the players execute it correctly, but the other team makes a great play to stop it.

While the team without momentum always seems to be out of position, the team that has it always is in the right place at the right time. That, my friends, is the power of cognitive momentum, and it has nothing to do with mass or velocity. It has everything to do with confidence.

Confidence is contagious, and it has a very specific feedback loop. We can thank evolution for this. I don’t need to tell you that life is risky. If we were constantly trapped in our own heads, overthinking every situation or making every choice by relying on the fight or flight mechanism in the limbic area of our brains, humanity would have faded out long ago.

Evolution gave us an advantage with our brains and social behavior. With these two gifts, we can learn and rationalize our choices, which let us dictate how much of our time and resources we’ll apply the next time the same opportunity occurs. Let me show you what I mean.

When someone believes they will be successful, has great effort, and takes massive action, of course they’ll find success. When someone is skeptical and filled with uncertainty, they never put great effort into their actions. And they get mediocre results, at best. In both of these examples, the outcomes will match the person’s belief, which reinforces the feedback loop. In other words, the rich get richer and the poor get poorer.

Momentum in the Weight Room

While admittedly I’m biased, I believe this feedback loop starts in the weight room because we have absolute control of the results we get while lifting. The athlete controls their effort. The athlete controls their recovery and nutrition. The athlete controls the outcomes.

There is far more control in the weight room than the competition arena where the coaches control the substitutions and play calls. The refs play their part, too. And while they never seem to make the right call, they keep both sides equally unhappy. So, the big question is, how do we keep people certain about what they’re doing in the weight room?

We never talk about in-season lifting as a maintenance program. In-season lifting is all about speed and power development, says @CarmenPata. Share on XFirst, we never talk about in-season lifting as a maintenance program. In-season lifting is all about speed and power development. Our athletes constantly get feedback about their speed and power by using my favorite tool in the weight room, the GymAware.

GymAware accurately measures bar speed or power for almost any lift, but we stick to our big three: squat, bench, and clean pulls. After our warm-ups, all returning athletes will go through what I call a ladder. They take one attempt at a given weight and record their speed or power result.

Video 1. One of our tight ends performs the squat ladder in week 9. (By the way, this is a 35-pound PR for him).

When using the ladder progression with in-season athletes, there are three rules the athletes must follow.

-

- Effort. They must hit their normal squat depth every rep. The athlete must have a controlled descent and then move the bar up as fast as possible.

-

- Cut off. Each phase has a minimum speed. Each athlete keeps going until their velocity is at or close to the minimum speed, or they cannot make the next weight increase.

- Stay healthy. There is a lot to account for during in-season training, and I know that some days the residual soreness of the prior game or a new illness or injury affects people. If an athlete feels terrible, they can stop at any time.

When the athletes follow these rules and continue to perform their ladders, training session after training session, two important things happen. First, the athlete will touch all the points on the force-velocity curve within the workout. Well, maybe they won’t hit the true maximum force part of the curve if they follow that day’s recommendation for the minimum speed. Assuming they do, they will hit strength-speed, power, speed-strength, and speed ranges, which are exactly what I’m looking to develop.

Once athletes work up the ladder, we know what weight gets them into each force-velocity zone & the weight to train in these zones the next session. Share on XSecond—and most important—we now can implement a personalized training program in a group setting. Meaning, once the athletes have worked their way up the ladder, we know what weight will get them into each of the force-velocity zones. And I know that the weights to train in the next training session in these zones might be the same, or they might change.

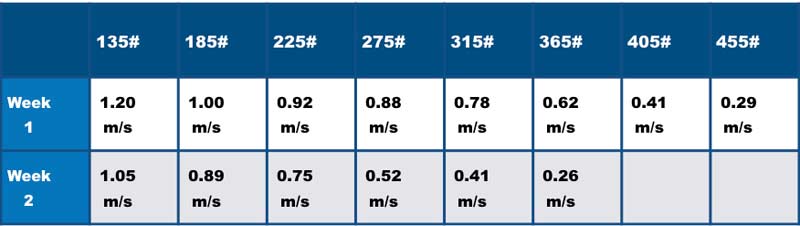

In the above example, the athlete’s program called for them to continue the ladder until they hit 0.5 m/s and then do reps on the minute with the weight that corresponded to or around 0.75 m/s. During the first week, their training weight was 315, but during week two they were at 225. You can see the difference between weeks one and two. This athlete had a few things going on, but the big thing was that they had significantly more plays going into week two than they did at week one.

Programing with the GymAware takes a little learning on everyone’s part. Still, whatever we’re working on developing with the current block, the athlete eventually understands that their program will adjust to where they are at when they walk into the gym. All the athlete has to do is adjust their program based on the results of their current ladder.

Using the above example, if we were to program the athlete’s week one weights on week two, we would have physically and mentally crushed that player. On the flip side, had I used their week two weights in week one, there wouldn’t have been enough of a stimulant to provide a positive training effect.

Just by following the ladder and velocity-based sets & reps, many athletes hit new maxes in the middle or end of their season, says @CarmenPata. Share on XThe crazy thing is that, even though the athletes only get one rep at each weight on the ladder, time and time again it’s proven to be enough stimulant to hit new PR’s in-season. Let me say that again. Just by following the ladder and the velocity-based sets and reps, we have multiple athletes hit new maxes in the middle or end of their season. Considering that my in-season training emphasis is on developing speed-strength and power, not maximum strength, I’ll take new PRs as a nice side effect.

Predicting Readiness and Game Performance

When I first started using the ladder system with our teams, we were experimenting with the idea of velocity-based training. Our priority was keeping people in their velocity zone, but we also happened to keep track of the velocities of everyone’s warm-up weights.

The ladder idea was born by an accident that has become one of the happiest I’ve experienced in the weight room. It wasn’t until we started plotting these data points that any of us understood what we had in front of us: a force-velocity curve specific to each individual athlete waiting to be discovered. Sure, it took a little Excel magic to make it look pretty, and it took time to evolve to its current form. Now, by the end of each training session, we generate reports that look like the one below.

Depending on people’s backgrounds, this report either has too much or too little information on it. For my staff, we are most interested in the actual data that is hiding within the curve itself. The red line is the average personal velocity for each of the weights, and each dot represents the specific result and day we tested the ladder. As I said, that’s the data my staff members like to dig into—but our sport coaches are more interested in the predicted status of the athlete.

The predicted athlete status concept took some time to develop. We started looking at the massive amount of data sets and then asked how the data we had correlated with the athletes’ performance in practices and games. After all, our job is to make sure our athletes are playing to the best of their ability, so why wait until practice or a game to find out they weren’t playing very well? We had the tools in front of us with the GymAware data and the observational data the sport coaches gave us on how their athletes performed. Now, we just needed to put it all together to create a model that could predict game performance.

Pretty cool, right? Yeah, I think so too.

Performance and observational data let us create a model to predict game performance, says @CarmenPata. Share on XIf you’ve ever worked with athletes in the middle of their season, you know there will always be fluctuations in their performance. The grind of the season wears people down, and there are always small nagging injuries. Then there are the outside influences like sleep, family life, and in my world, academic pressures.

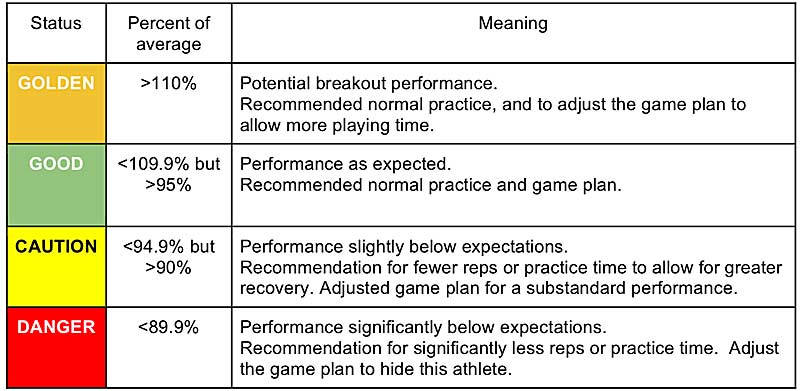

All of these factors and others combine to make subtle changes in an athlete’s day-to-day performance. The question we kept trying to answer is: What is an acceptable drop in performance? Looking back at all our empirical and anecdotal evidence, we came up with four categories to rate the athletes.

It’s very rare for athletes to rate in the top GOLDEN category. Typically, we’ll see this with student-athletes who compete in the fall sports. I wish I could say the only reason they perform greater than 110% of their average is that I’m that good of a coach, but I can’t.

Usually, the athlete didn’t do much if anything over the summer and is experiencing super-compensation from training. We’ve also seen athletes who took their training very seriously have a great week. Whatever the reason, they feel that they’re on top of their game, and if they test into the GOLDEN category, everyone expects big things from them at the next game.

Primarily, we see athletes in the GOOD category. There might be a little drop in their numbers, but it’s within the expected range. They are in-season, and accumulated fatigue is a real thing, but they should be able to live up to their practice and game expectations.

When the fatigue is too much, we see people slide into the CAUTION group. We hear back from their coaches that they were a “half-step slow.” Typically, these athletes haven’t recovered and need a little more rest to get back into the green GOOD category. That means taking fewer reps at practice or even having a day off. This was a hard sell to coaches at first, but now they understand that a tired athlete is a slow athlete, and sometimes rest is best.

That brings us to the last group: the red, DANGER category. This group is now significantly slower and weaker in the weight room. At this point, their coaches usually say they’re a step or two behind. When we have athletes in this category, our first move is to have a conversation with them to help everyone understand why. We’ve come to learn that when people are in the DANGER category, there may be a few things going on. Typically, it’s any combination of the following:

-

- They are sick, either expressing or just starting to show symptoms.

-

- They are injured, and we know about the injury, or they were trying to “grind through” it without seeking treatment.

-

- They are overly stressed.

-

- They are not eating or drinking correctly. Or they’re hungover.

-

- Their training is not correct. Either they are under- or over-trained.

- They didn’t give their normal effort.

Hopefully, we can have an open and honest conversation about what is causing their decreased performance. Most of the time, this helps us correct the problem within a week by making routine adjustments to the athlete’s daily schedule. Some of the adjustments can be as easy as going in for treatment for an injury, changing what they’re eating and drinking, or taking a day off to get physically or mentally right.

Whatever the underlying reason for their decreased performance, we can only find out why they are in the DANGER category if there is a conversation. This helps the coaches plan for poor practice and game performance. Also, because they do not see as big of a role for the game, they take fewer reps in practice. Believe it or not, that’s OK since fewer reps mean fewer exposures to injuries. We’ve also seen an increased injury rate for the people in the red group. I’d rather see a reduced week of practice instead of a week (or more) with them sitting in the training room rehabbing.

Wrapping Up

I admit, my take on in-season lifting is different than that of many others. While we all do what we think is best for the athletes we work with, this is where momentum comes back into play. If you’re constantly telling your athletes that the only goal is to maintain their strength or speed during the season, you’re setting their belief patterns.

At the start of this article, you saw how beliefs lead to action. If the athletes believe what happens in the weight room is not important, whatever actions they take will never be done with great effort. They believe it’s OK just to have an OK lift since we’re not pushing to get better. That cycle of belief and action creates momentum heading down a path that I don’t ever want to go.

On the other hand, if your athletes believe in the mindset of attacking everything they do, that will create momentum, which will take you down a different path. The belief in attacking a workout, even in the middle of the season, puts the focus back on the athlete to control the things that they can control.

The belief in attacking a workout, even in the middle of the season, puts the focus back on the athlete to control the things that they can control. Share on XI’ve been involved with sports long enough to understand that one of the hardest things to do is get in the gym and attack a workout while in the middle of the season. But that’s exactly what I ask athletes to do. Sure, we can go through all the physiological changes I expect the athletes to get from the program, but the greatest transfer of this style of in-season training happens to the little grey and white cells that reside between their ears.

It’s about building momentum into the next game. Instead of focusing on all the things they cannot control, we constantly reinforce that when they learn how to push and fight through a workout, they will push and fight through a close game.

Very few, if any, of the thousands of athletes I’ve worked with initially had the mindset of always attacking their workouts. Luckily, this is a teachable trait as long as someone is around repeatedly telling them that giving up is not OK. I believe the trait that humans have that separates us from all other life is the dignity of choice. We can decide what we believe and decide how much action to take because of that belief. From everything I’ve witnessed in my life, the only real choice for any issue is taking the easy way out or the hard way out.

You see it in sports all the time. A team gets down, and they choose to give up—the easy way out. Their effort disappears. Their intensity disappears. Their will to win disappears. In my experience, this is what happens to people who haven’t learned how to get through hard times, like attacking a lift even when they don’t want to.

Momentum in sports starts in the weight room. It’s up to the coaching staff to decide which direction the momentum will take the athletes and team—down the path of the easy or hard way out. Remember, all it takes to build momentum is a push from the coaching staff.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF