GPS tracking is nothing new to football, and I have been blessed to have been around a different GPS tracking system at every stop in my career. My responsibilities have morphed from placing out the vests in athletes’ lockers as an intern, to downloading and reporting as a grad assistant, to being the head strength coach conversing with the head football coach about alterations to the practice plan. These organizations have spent money on GPS because they wanted to be at the forefront of physical preparation. By seeing the many systems and approaches to its implementation, I’ve been able to appreciate the value that GPS brings from day one.

By seeing the many systems and approaches to GPS implementation, I’ve been able to appreciate the value that it brings from day one, says @Torinshanahan42. Share on XThe ability to quantify the game removes the guessing about what preparation should look like for optimal performance. While I’ve seen the benefits, I have also seen the costs and understand why every team does not have GPS. My hope with this article is to help provide the lessons I have learned with GPS and bring them to your team. Hopefully, you can use these lessons to improve your understanding of the game and weekly preparation.

It is important to note that the data I share below reflects the data collected at my most recent institution, a Division 1 Patriot League university; however, the lessons I have learned, examples, and ideas for change are lessons that come from my experience across multiple teams and conversations with peers.

Learning these lessons has been a long process, and I am nowhere near finished—it all started one day when I asked my boss to take the next step past just passing out vests and units. My first assignment was to help find sets of normal practice values. When I started looking, there was very little useable information out there—or, at least, it was hard to find.

Data with context can become information. There typically is either data without context or a lack of data, and it’s just stories. I hope to bridge that gap by providing some summarized data with context so that it can help you.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=11160]

Game Demands

Preparing for something you do not understand is difficult. Preparation for football games starts by analyzing the game itself, and football becomes tricky to quantify not because of a lack of resources but because of its nuances. Multiple positions are drastically different from an anthropometric measure standpoint, as well as the drastically different roles. The nuances compound when you add offensive and defensive schemes to the mix, where the same position can have different roles and demands due to the use of that position in that scheme. The final compounding factor is the individual’s role on the team, whether they are the star player, a special teams star, or another part of the rotation.

Factors impacting game demands:

- Conditions: Field type and weather conditions.

- Style of play: Tactical schemes of offensive and defensive.

- Position assignments within that scheme.

- Position: Amount of rotation at that position.

- Role: Star player, role player, special teams guy.

The point of explaining the different factors that go into the measurement of game demands is so we all understand that every team will have different demands. Now I will try to provide general averages to game demands with context, so you can understand how they might or might not relate to your team.

GPS metrics are actually very easy to understand. There are metrics for the volume of work, the intensity of that work, and the density. These are all the same variables we utilize in the weight room. Practice and games are external load stimuli to the body, just as resistance training is. The tracking system we had during the collection of this data set is Polar Team Pro.

GPS metrics are actually very easy to understand. There are metrics for the volume of work, the intensity of that work, and the density, says @Torinshanahan42. Share on XTo quantify volume, we utilized their muscle load metric, a measure of anaerobic power movements summed together (or the stress applied to the body). Muscle load per minute is our intensity metric, as this is the rate at which external load is applied to the body. Velocity is the king of intensity. High-velocity and high-acceleration movements place enormous forces and stressors on the body. Respecting the volume of these instances is important for the preparation and modulation of performance.

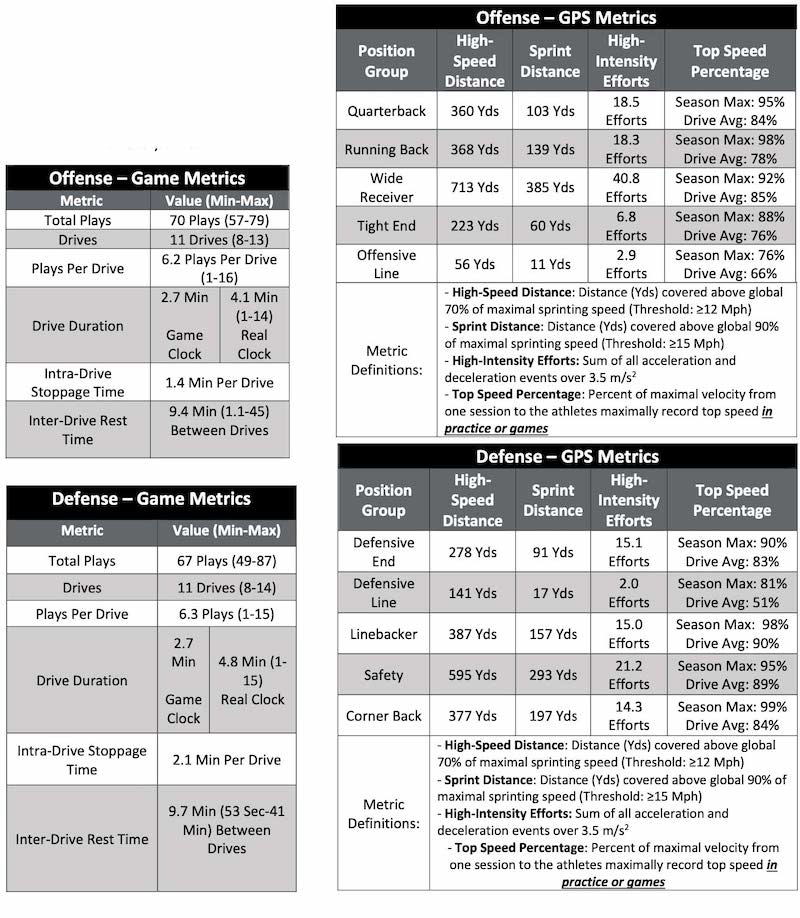

We look at high-speed distance (global >70% maximal sprint speed), sprint distance (global >90% maximal sprint speed), and high-intensity efforts (count of occurrences of acceleration or deceleration greater than 3.5 m/s2). Polar Team Pro utilizes global thresholds, which means offensive linemen are held to the same velocity standards as wide receivers for all velocity-related metrics—this is important to note when looking at the following data.

Offensive Game Play

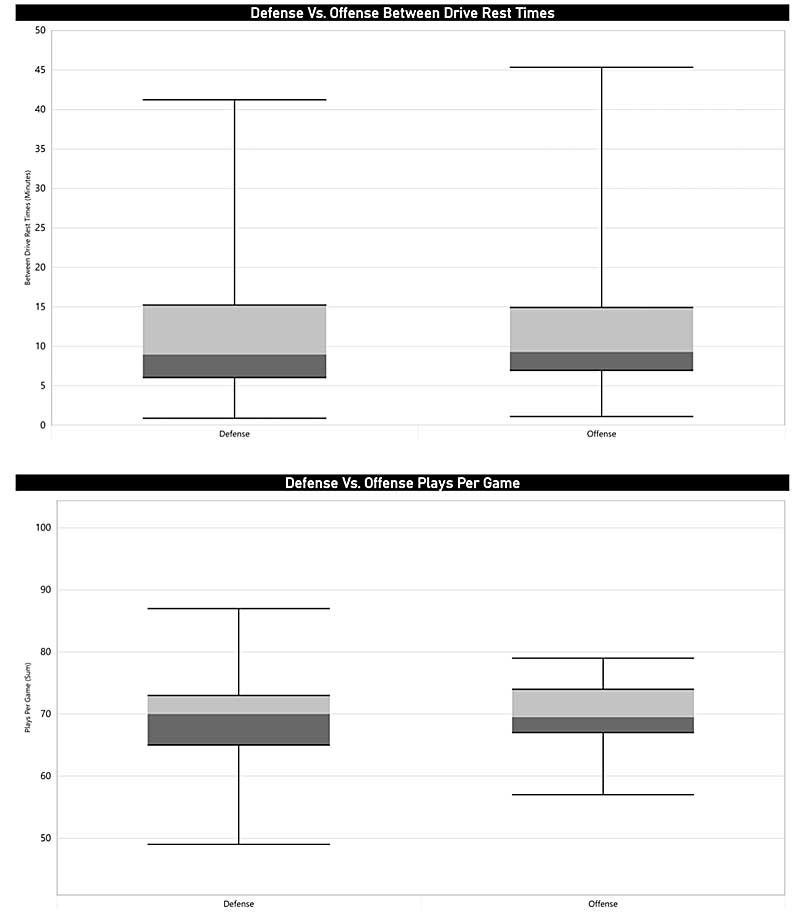

Our context: We play in a spread-style offense with a pretty typical tempo. Our running backs rotate the most, but we tend to focus on the guy with the hot hand. Wide receivers tend to rotate with personnel packages. I would call it a standard offense in modern-day football. We averaged 11 drives per game, totaling 70 plays (on average). We possessed the ball for 29.9 minutes of gameplay over 54 minutes of the real clock. The offense averaged 6.2 plays per drive while on the field for 4.1 minutes of the real clock before resting for 9.4 minutes between drives.

Our GPS metrics for offensive players followed normal patterns I have seen with previous teams. Quarterbacks do vastly more in games than they ever do in practices. This is because of protecting quarterbacks in practice. Offensive linemen also have very low volumes in practice unless you have an offense that pulls offensive linemen downfield.

There is a need for metrics specific to line players to quantify the physical demand of pushing other grown men around. Skill players, on the other hand, have physical demands that are very easy to track. Wide receivers and running backs get put in space and are allowed to do their thing: they rack up large volumes of yardage trying to stretch defenses.

Defensive Game Play

Our context: We play in what I will call a 4-2-5 defense. Our defensive line rotates quite frequently, while the defensive backs rotate a typical amount between drives. Our linebackers do not rotate very often. I would also say we run a pretty standard modern defense with a good mix of zone/man and mixed assignments by position. We average 11 drives on defense while facing 67 plays. We defended for 30.1 minutes of gameplay over 60 minutes of real time. On average, the defense had 9.7 minutes to rest between drives before playing for 6.3 plays over 4.8 minutes on the real clock.

The external load experienced by our defenders followed normal patterns. The defensive line has similar problems to that of offensive linemen in quantifying their demands—the primary difference is that they still rack up decent volumes of yardage chasing down the ball carrier. Linebackers perform tremendous physical work, including running from sideline to sideline while chasing down the ball carrier. Safeties must fly downhill from depth, leading to the highest high-speed and sprint distance.

A defense’s performance in a game can be estimated by their top speeds. Higher top-speed percentages mean they had to sprint to catch up with someone—nothing good happens when defensive players are trying to catch up to someone. You will see this as the top speed an athlete hits in a game on defense is usually higher than that of their offensive counterpart, but their offensive counterpart will have a higher average percentage of top speed.

The top speed an athlete hits in a game on defense is usually higher than that of their offensive counterpart, but their offensive counterpart will have a higher average percentage of top speed. Share on X

Offense vs. Defense

The averages for offenses and defenses will look relatively similar, especially when you play similar offenses to the one you run. The difference comes in how your opponents execute their own scheme.

Your defensive players will be exposed to greater variability in the specific demands placed on them each game. It is important to understand this during your practice week: all the workload put on your players must be accounted for. When one of those days has a higher variability, the other days must be more specific to account for swings on the variable input day, game day.

There is more opportunity for swings in practice volume from offensive players because you know what they will handle in the game. You can work the math with them, while the widely unknown variable of the game for defensive players demands that practice be more routine. Increasing the variability of their practice routine exposes them to the extra risk of injury due to intensive swings in their acute:chronic workload from (relatively) very light or very heavy volume games. In short, be more careful with defensive players because of the variability of their game demands.

Practice Demands

Football is a sport where we spend far more time preparing for the game than playing it. Hours of practice, drill after drill, and countless reps are utilized to teach technical skills and tactical concepts, develop physiological fortitude, and train the body physically to play football.

It becomes incredibly important to understand the physical load on the body in practice. This is compared to game demands to understand how well the athletes are prepared, says @Torinshanahan42. Share on XWith the amount of time spent at practice, it becomes incredibly important to understand the physical load on the body in practice. This is compared to game demands to understand how well the athletes are prepared. Athletes can be overtrained and play in a fatigued state—putting them at a higher risk of injury over time—or athletes can be undertrained, meaning they are not prepared for the demands they will be subjected to, also increasing their risk of injury.

Precisely what a practice should look like is beyond this article. What I would like to share are generalized trends in the practice demands of football players.

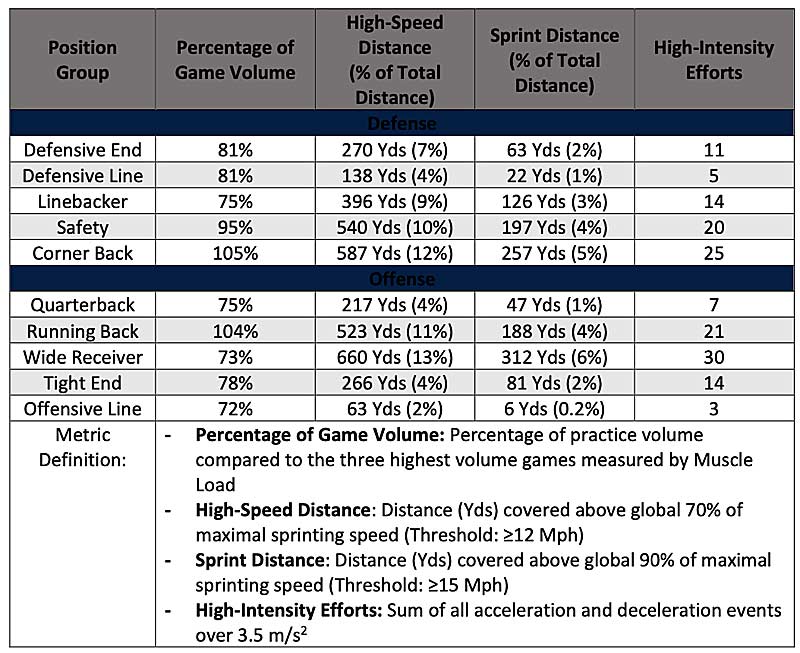

Trends

Defensive coaches push guys harder in practice, and defensive players will do more work per practice than their offensive counterparts. This becomes especially true when compared to the game demands for those positions. This year, defensive players on this team averaged 87.4% of a game’s volume per practice, while offensive players averaged 80.4%. Offensive players physically cover more distance in practices, but again, this is relative to what they do in games.

In practice, both sides of the ball have similar opportunities for high-intensity efforts for a couple of possible reasons. First, defensive coaches tend to keep rotating players in practices (similar to during a game). On the other hand, offensive coaches tend to rotate less in games or more in practice. This means that offensive players who play in games rack up more high-intensity efforts, while those efforts are spread amongst the position group in practices. Below I have included average practice external load volume metrics for both sides of the ball.

Lesson #1: You can do more, a lot more.

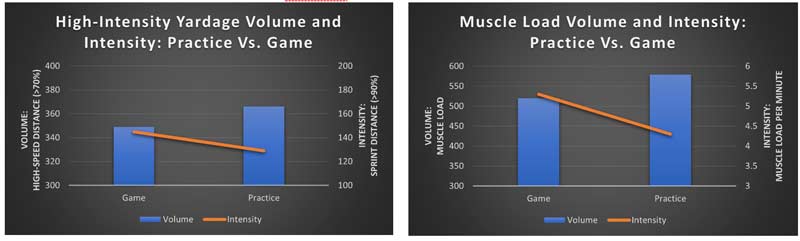

I think one of the barriers around GPS in football is that coaches see GPS as a limiter, something that tells them to do less on the field. They see reps as currency and duration as a requirement for the day to be profitable. The opposite, however, is true—volume is the cost they pay for each rep, and intensity is the benefit. Practicing at slower speeds than game intensity creates a challenge for transferring technical and tactical skills to the game environment. Situations happen faster than they’ve been practiced, putting the players a step behind.

I think one of the barriers around GPS in football is that coaches see GPS as a limiter, something that tells them to do less on the field, says @Torinshanahan42. Share on XPlaying at game speed in practice prepares players for what they will experience in games. Increasing the intensity is also a way to do more. Players experience greater total volumes of work if the intensity is increased since intensity is the rate of work per time/rep. In short, there is an opportunity for coaches to do more with GPS during practices; low-quality volume must be removed for high-quality intensity during practices.

Lesson #2: Practice is an important training exposure.

The volume of work that athletes are exposed to during the practice week greatly impacts their physical performance capability. This last season, we had 84 practices averaging 125 minutes for a total of 10,500 practice minutes. This a huge opportunity for sports performance coaches to train within the tactical and technical preparation of practice.

Another way we look at the amount of work done during the week is through game loads. The game loads metric is the number of games’ worth of volume of work athletes perform during the practice week. During the 12-week season, we averaged 2.8x game loads per week in practice, meaning we played almost three games to prepare for one game. There is a lot that can go right and a lot that can go wrong during all this time. Coaches need to be very intentional with this time to prepare players to be successful in competition.

Lesson #3: Prepare them for practice, not games.

Players have drastically greater exposure in practices, and practices have different demands than games. While the focus is winning games, the number one objective to accomplish this task must be making sure our players, especially our best players, are on the field.

If practice is a large exposure to training, then players must be prepared to handle practices, not games. I once designed my training, especially fieldwork, to the demands of games. An example is that most wide receivers cover about 250 yards of sprint distance in a game. In the summer, we build to and then consistently expose them to this type of sprint yardage in training. Having done this volume of work in a controlled setting, they are less likely to be hurt in the open environment of games doing the same volume.

If practice is a large exposure to training, players must be prepared to handle practices, not games. But practices have different exposure to external loading, with very different rest periods. Share on XBut practices have different exposure to external loading than games, with very different rest periods. Practices end up being more sustained, whereas games are highly intermittent with long rest periods. The differences are significant enough that to keep athletes healthy, they must be prepared to endure practice first. The volume of practice before the first game will properly prepare athletes for the game. This approach comes from keeping our primary job in mind: reducing the risk of injury.

Differences between games and practice:

- High volumes of work

- Average 349 high-speed yards in games vs. 366 high-speed yards in practice

- Average 520 muscle load in games vs. 579 muscle load in practice

- Muscle load = Polar’s version of player load—a measure that summarizes movement in all directions by intensity for the total load placed on the body

- Low intensity of work

- Average 145 sprint yards in games vs. 129 sprint yards in practice

- Average 5.3 muscle load per practice in games vs. 4.3 muscle load per minute in practice

- Muscle load per minute = intensity of loading as measured by muscle load

- Different rest periods are found in games

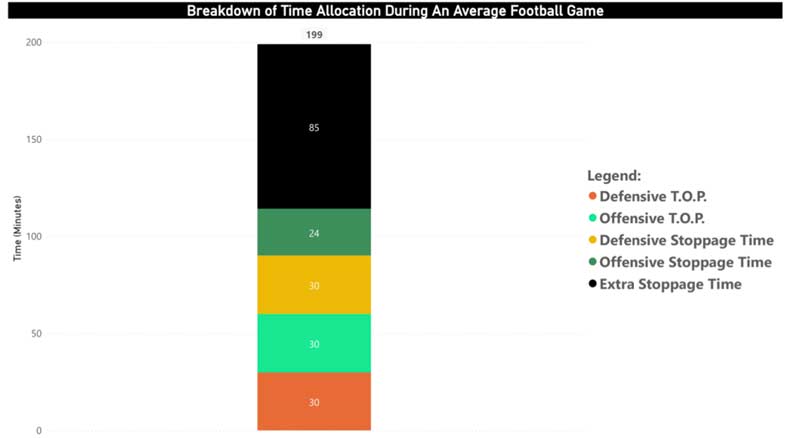

- 86% of minutes are spent not playing football in games vs. one 5-minute rest period and four 1-minute rest periods.

- 1:3 vs. 1:5–7 work:rest ratio

- 86% of minutes are spent not playing football in games vs. one 5-minute rest period and four 1-minute rest periods.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9062]

Summary

In my several years of experience with GPS, I have seen multiple ways to implement the technology. I have also seen multiple ways to practice and prepare for games. The lessons I have learned are straightforward:

- We can do more in practice with higher intensity.

- We need to be intentional about the training exposure of practice.

- Players should be prepared for the demands of practice.

Practice involves lots of work with less rest. Games have extraordinarily large amounts of rest time between drives, allowing for high-intensity actions placing great stress on athletes. Offensive and defensive players are exposed to significantly different demands in practice and games, as defenses must react to opposing offenses. Combined, this is all information I have learned by using GPS with football. You can bring these lessons to your team to help better understand the demands placed on them.

I have included some extra resources that I found useful on the journey.

Lead photo by Bradley Rex/Icon Sportswire.

Resources

The Process: Fergus Conolly and Cam Josse.

Brad Dixon, Tony Holler, and The Track Football Consortium.

I also recommend just getting GPS and exploring.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF