More and more coaches are posting videos of their athletes online than ever before. While the promotion-style social media clips are more of an attempt to be relevant, the ability to have video recorded and shared properly demands an intervention. I have twice written specifically on video analysis and got a huge response, as well as requests for merging timing and other performance data with video. Coaches no longer just want to know how fast an athlete is sprinting; they want to know how to make them faster by improving technique.

Coaches no longer just want to know how fast an athlete is sprinting; they want to know how to make them faster by improving technique, says @spikesonly. Share on XIn this article, I cover the steps necessary to take video and get more out of each clip by leveraging electronic timing. For years, I have promoted the balance between kinetic and kinematic data, and while electronic timing isn’t truly a kinetic measure, you can infer a lot about how forces interact with an athlete’s technique when fusing both data sets. If you are a coach or sport scientist and need practical pointers on making the workflow and process faster and more convenient, this blog post explains what to do and provides a spectrum of upgrades for the serious analyst.

Buy the Right Tools for the Right Job

I have seen a lot of video apps being promoted—usually light sport science solutions that help with timing, lifting, jumping, and even motion analysis. Most of this article covers sprinting, but if you are involved in other sports, you can use this information to build a framework for better fusion of video and sensor data. So far, I have not been impressed, as the market turns a coach into a hopeless servant spending an enormous amount of time crunching data on their phone or tablet.

I look at this as an example of “techno candy,” or how technology is sold for acute interest but has poor nutritional value in the long run. Coaches should be focused on making data actionable, not doing monkey work in the way of mundane tasks. Thus, using an expensive app is simply just time luxury that nobody in their right mind should invest in.

Only a few of the apps on the market are real-time, and if they are, they are so limited that they are unable to manage the team environment properly. I contributed to SimpliFaster’s Buyer’s Guide for Sports Video Analysis because the company’s vision is to help athletes and coaches do their job better and easier, even if they use hardware and software from another vendor. When buying technology, you need to know what you want to do and then find what is best for your budget and knowledge base.

It’s perfectly fine to have a smartphone and use it as a camera but be warned: I have done this myself and will tell you as an athlete, it creates a barrier when a coach is constantly behind a smartphone or tablet. Today, if I am doing any instruction, I use a remote, as it purposely doesn’t look like I am distracted by the phone. The culture of using a smartphone in public is still dated and no standard of etiquette exists, so I prefer remotes or dedicated recording periods with high-end cameras.

Technology usually encumbers professionals; the right technology gives a coach a freedom that feels truly liberating, says @spikesonly. Share on XIf I have to make a recommendation, use your phone for a remote and use a small tablet with a construction site-proof case. Coaches need to replace their clipboard with it and carry it like a small satchel so they can be untethered on the go. Technology usually encumbers professionals; the right technology gives a coach a freedom that feels truly liberating.

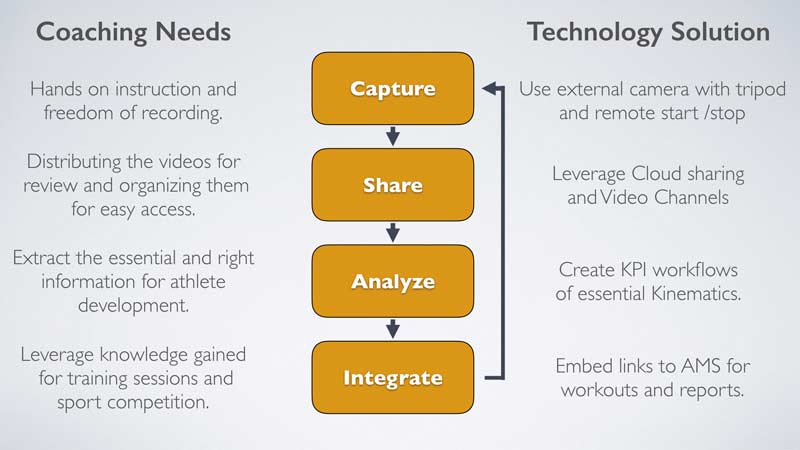

Now come the choices necessary to get started. You can continue to use a smart device, as the cameras available are simply amazing, but I still recommend an external camera with a tripod. While I admire coaches who use their smartphone, when you add a commercially available camera and tripod, the game changes. Coaches who want to coach and not be videographers should focus on standardizing their practices so they can be behind the scenes in teaching and training and not behind a camera all day. Most of what coaches do outside of feedback and instruction is literally running the show like the director of a play, not the director of a movie.

Of course, you will need to invest in electronic timing, and this can be conventional split-style capture such as Freelap or continuous such as laser and player tracking units. Keep in mind that the IMU market is in a grey area that doesn’t have a lot of precision yet to really know athletes’ true speeds, but the technology is useful for team sport practices. It is not ready for prime time for several reasons. Peak velocity readings and even profiling are solid, but early acceleration is not valid yet, in my opinion.

What Coaches Should Do with Video and Timing Devices

Make sure you know that execution requires a full understanding of coaching theory and not just looking for the next sexy metric. A good example of applied knowledge is Ken Clark, who is both a coach and a researcher. If Ken doesn’t use it, it’s likely impractical or too costly. I try to make sure I check in with Ken from time to time just to make sure I am not pushing the envelope unnecessarily.

Video should be used for kinematics as much as possible and looping at a slower rate is better than slicing up the clip into still photos, says @spikesonly. Share on XCoaches need to know what they should not bother with in regard to timing and when descriptions of data don’t lead to prescriptions in training or instruction. Ornamental data is interesting and fun to talk about, but discussions in bars or conference hallways are rarely applied back on the track or field. When using video, please focus on motion review and not data that could have been used in an automated, real-time fashion. Video should be used for kinematics as much as possible, and looping at a slower rate is far better than slicing up the clip into still photos. I do believe that individual frame learning is paramount, but that’s for textbooks not a living world with human eyes.

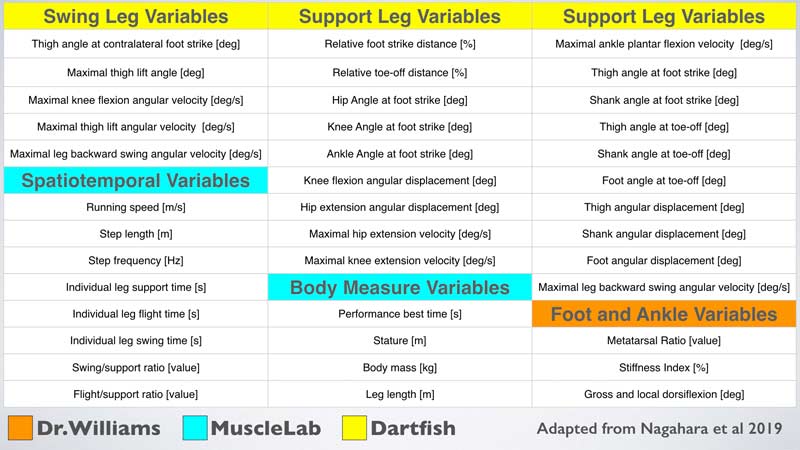

Coaches and biomechanists can choose to do a lot with video; they can even elect to do qualitative analysis and look at less-used information like facial expressions and more psychological aspects of the recordings. Generally, coaches should look at positions, angles, and the relationships between the body’s regions in time and space. The amount of granularity is up to the coach, as some situations merit a lot of narrow focus, while others require a wider zoom.

A coach may often not have to measure at all, just look at the film in very slow motion and at full speed over and over again. Sharing the videos directly with the athlete with and without annotation or narration is more important than breaking the film down. It feels powerful to write or measure on the screen, but most of what I have seen is fluff disguised as kinesiology.

Now for the heart and soul of this article. What do you get when you actually combine data from timing devices and video? Using a video with pre-measured landmarks enables a coach to get splits manually, but this is time-consuming, and you should only do it when an athlete has plateaued from training enough to be a worthy candidate. Segmented time splits help determine mean or average speeds that you can use to determine what qualities need to be managed properly. Absolute measures and relative measures are the ultimate checks and balances to a program.

Countless times, I have seen coaches post about an adolescent child running faster than nearly the entire professional sports league, and I’ve wasted energy trying to convince them that they don’t have the next Usain Bolt. A flying sprint is the most useful measurement, as a short maximal effort run with a sufficiently long buildup can reveal so much that coaches don’t need to do much else for speed appraisal. Jumping and throwing are far more complex interactions and require more study and coaching knowledge. On the other hand, sprinting, while natural, does involve a lot of understanding of constraints anatomically and physiologically, so while elegant to watch, it’s a deceptively simple motion to the untrained eye.

Next-Level Integrations from Ergotest and Dartfish

Those who invest in Dartfish and Ergotest will find themselves at a serious advantage over their competitors. Time after time, other companies have tried to provide a similar experience, but they later realized that what they offer pales in comparison or isn’t useful for professionals. With computer vision, many times an algorithm glitch renders data inaccurate or invalid, especially for more complex measures in bad environments. I do think AI is the future for most video collection, but currently there are not enough tools available to do this inexpensively for widespread use. In the meantime, some manual work and automated sensor technology are the best options today.

Some information that is useful, but not video capture specific, are contact times and air time, continuous horizontal velocity, muscle activity, and estimated joint stiffness (quasi). My recommendation is to leave those aforementioned measurements to the MuscleLab (Ergotest) and save video for kinematic information. You can use wearable IMUs for joint information, but to me, simple data is more malleable in the real world. Deep diving is great, provided you come back to the surface and work with pragmatic feedback such as posture, timing, and ranges of motion.

Deep diving on data is great, provided you come back to the surface and work with pragmatic feedback such as posture, timing, and ranges of motion, says @spikesonly. Share on XMuscleLab stands apart from the rest of the field due to the simplicity, speed, and synchronization benefits of different sensors working together. Even if you don’t use MuscleLab for speed measurement, you can combine the data later. While this adds a little time and is a bit limited, it’s worth keeping your timing system and using a post-session merge.

Video 1. Athletes can video and time on their own during warm-up to see how readiness rises and falls during remote training. Autoregulation is very powerful but make sure athletes are experienced as trainees before they handle corespondance workouts.

So, what is so great about Dartfish? The Pro S product makes its mark when uploading sensor files into the video, so you have a surreal overlay that literally transforms data into digital tapestries of information. Stromotion and other effects turn the timeless photo sequence of the past into a collage of images that are illustrative and not decorative. My complaint with many of the video effects is that they look impressive at first glance but fail to be useful when actually trying to fix errors and mechanical faults. I can go on and on with touting the Dartfish experience, but you have to commit to making video a serious staple in your program before fully appreciating the difference.

Testing and Training with Video and Electronic Timing

The line is now blurred between testing athletes and continuous training. In the past, a test day was done periodically; today, nearly every session is a test in some way. The main benefit of electronic timing is simply knowing how the athlete is improving over time. What isn’t really clear is how, since similar athletes may improve at different rates for different reasons.

Video reveals why an athlete may be struggling or succeeding in a program. The challenge is knowing how to make the right decisions in the program, especially when athletes hit a wall with improvement. Genetic ceilings aside, the difficulty with video is knowing what to look for and what is modifiable with interventions. Often, simple exposure to various speeds and drills will self-organize an athlete’s running mechanics into a better technique. Nothing is guaranteed, as you can’t hope that chaos will create order all the time.

Workflows and managing the training process aren’t easy, but I have a cheat sheet from years of distilling some bright experts in the field into one chart. The cornerstone of everything I do is founded on goals derived from realistic expectations based on profiling and common improvement rates. The chart is simple: It’s a combination of looking at what has worked in the past and what has not, and the ability to evaluate the gaps that hinder the athlete from being more successful. Simply put, where is the athlete now and what is their trajectory in the future?

Training with data means the data is instantly available to the athlete and coach. Anything post session means data is guiding the program and not the session. While that seems like a minor detail, the truth is most interventions are often late or gradual, not immediate.

Without getting into the minutiae, video feedback is not usually immediate unless athletes are able to see it during the session, and for the most part, the likelihood of a dramatic change at late stages of development is low. Also, if feedback is effective, an athlete will eventually resolve mechanics, and the name of the game becomes simply getting faster, be it horizontal sprinting, taking off from the ground, or releasing an implement.

If feedback is effective, an athlete will eventually resolve mechanics, and the name of the game becomes simply getting faster, says @spikesonly. Share on XTeam sports are starting to evolve so that scrimmages and other practices are near real time, meaning they show videos during training with the help of either a jumbotron or large tablet during rest periods. I am not sure how that helps beyond common film review, but if the athlete is immediately aware of their errors or success, I think video will connect to the athlete far better.

A lot of athletes have grown up in the YouTube era, watching games and highlights online instead of TV. Unfortunately, just watching sport online rarely harnesses the power of video. You still need coaches to help explain what athletes need to do better or at least have a discussion about what they are thinking. Sometimes—more likely most of the time—breakthroughs happen when talent meets opportunity with team sports, so it’s not always a top-down improvement.

Start Small or Go Big

It doesn’t matter if you want to use your phone and record a few videos or wish to invest heavily in video and timing—you will get what you pay for. When spending small amounts of money on technology, you are committing a fraction of your wallet but giving up a massive set of hours in the long run. When investing the other way, you spend a lot of time upfront both with education and expenses but will love things later when everything is automated and streamlined.

I do both, as the flexibility to travel light or be mobile is huge, and I have coached high school and small college for years without any real budget. On the other hand, I currently do more and more deep analysis for other coaches, so I need the firepower to provide more than they can. Whatever you do, respect the video and start leveraging it correctly, even if it’s just for Instagram or Twitter.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF