Golfers don’t sprint. They don’t even jog. Old men can ride in a cart and play 18 holes without ever working up a sweat.

How could a sprint program have anything to offer to one of the world’s least athletic sports?

Golfers aren’t athletes? Before I get inundated with hate mail, let’s discuss “athleticism.”

Like every coach, when I say, “That kid is an athlete,” I’m saying that kid is fast and explosive. In my days as a basketball coach back in the ’80s, I coached a normal kid who averaged 25 points per game. He was a TERRIFIC PLAYER but was slow and couldn’t dunk. I got in trouble on a post-game radio show for saying the kid wasn’t very “athletic” after he scored 40 points in a game.

Call me crazy, but building athleticism will make any athlete better at their sport. More specifically, I encourage athletes to sprint fast, lift heavy, jump high, jump far, and bounce.

Golf coaches, please don’t quit reading! I know exactly what you’re thinking. When playing golf, players NEVER sprint, lift, jump, or bounce. NEVER. So why should we listen to this crazy track coach?

Stop Reverse-Engineering Your Sport

Seems all my ideas are counterintuitive. What’s wrong with me? It’s so much easier to just go with the prevailing winds. But then again, only dead fish swim with the current.

It makes perfect sense to train athletes specifically for their sport. Here’s the problem: training specifically for a sport doesn’t create better athletes, says @pntrack. Share on XIt makes perfect sense to train athletes specifically for their sport. Swimmers need to swim, hockey athletes need to skate, and golfers need to swing. Here’s the problem: training specifically for a sport does not create better athletes.

In football, specificity will tell you that wide receivers need to do 60 sprints. Offensive linemen only need a couple of quick steps and to push things. But train specifically, and you will ignore athleticism.

In soccer, goalies don’t have to run or sprint. Other soccer athletes need to train like cross-country runners to prepare for up to 9 miles of running in a game. But train specifically, and you will ignore athleticism.

If Stephen Curry runs 3.1 miles in every basketball game, he better be doing daily runs of 3.1 miles, right? Nope, Stephen Curry needs to be the best ATHLETE he can be, especially as he ages.

At the risk of becoming redundant, stop training golfers as golfers!

Why Sprinting Makes a Better Golfer

Linear maximum-velocity sprinting, in spikes, getting timed, is the most extreme movement of the human body.

I repeat, linear max-velocity sprinting, in spikes, getting timed, is the most extreme movement of the human body.

Whether you are Usain Bolt sprinting at 27.6 mph or a 64-year-old track coach topping out at 12 mph, sprinting requires maximal involvement of the central nervous system (CNS). Nothing else comes close. In the weight room, maximum bar speeds never exceed 5 mph.

The CNS controls all movement, and the brain is a protective mother. Kids with poor eyesight never win races (consider the eyes as a part of the brain).

Speed is more electrical than muscular. Muscles are dumb; they do what they are told, at the speed that the CNS tells them to contract. Speed is neurological.

Since all movement is neurological, controlled by the CNS, speed is the tide that lifts all boats. When you train the EXTREME, you train the RANGE. Improving max speed not only improves efficiency at sub-max speeds, it also improves an athlete’s ability to move in all directions. I’ve often timed my track team running backward. Guess who wins? Yep, the fastest guy running forward is also the fastest guy running backward because the CNS controls all movement.

When you train the EXTREME, you train the RANGE. Improving max speed not only improves efficiency at sub-max speeds, it also improves an athlete’s ability to move in all directions, says @pntrack. Share on XAcceleration? The fastest athletes at max speed are your fastest accelerators.

Let’s take this to the next step.

Want to improve skate speed for hockey players? Sprint.

Want to improve a basketball player’s quickness and ability to jump? Sprint.

Want to improve as a swimmer? Sprint.

When you train the EXTREME, you train the RANGE.

Unless you play a sport where there is absolutely no movement, you better be sprinting. Having said this, I’ve spoken to people who hypothesize that improvements in sprint speed may contribute to cognitive speeds. Chess?

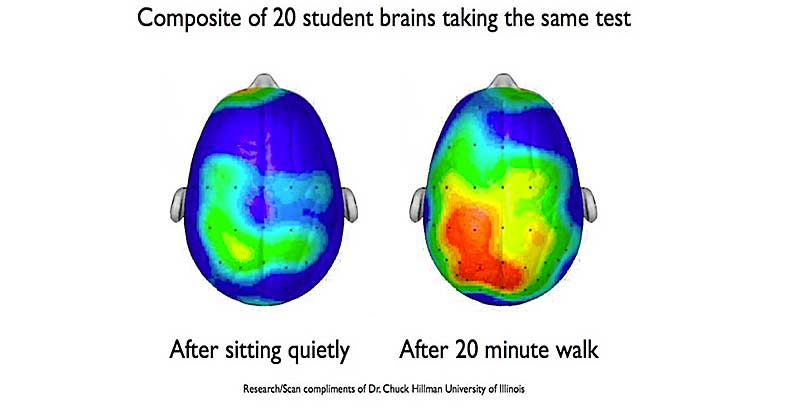

Speaking of cognitive improvements, I study writers. Seems every writer claims WALKING is critical to the creative process. Writer’s block? Go for a walk.

My hypothesis: If walking is so good for the brain, the most extreme movement, sprinting, may be even better. What if we added a third composite brain to Dr. Hillman’s research? What would a brain look like after a 20-minute sprint workout? I predict all reds and yellows. We might be on to something!

Never Slow Down, Never Grow Old

Tom Petty knew his stuff.

I believe the fountains of youth are:

- Weight

- Speed

- Sleep

Those three things are related because gravity is the number one enemy of speed, so being overweight makes you slow. And without sleep, the CNS does not reset and gets sluggish. Tired and sleepy people are slow. My final take on this subject: sprinting is really good for controlling your weight and getting a good night’s sleep.

I would love to see someone bold enough in the baseball world to train aging players differently. Instead of lifting and doing cardio, sprint-train aging baseball players. From what I know, no one does this. No one. I’m sure people will argue that they “run sprints” or that “running poles” is sprinting, but it’s not. Sprinting is not “running fast” or “working hard.” Sprinting is different.

I would love to see someone bold enough in the baseball world to train aging players differently. Instead of lifting and doing cardio, sprint-train aging baseball players, says @pntrack. Share on XMy definition of sprint: sprinting in a straight line at max speed, wearing track spikes, and getting timed. If you don’t push the limits of the CNS, the CNS gets depressed, and speed deteriorates. The road to getting slower is all downhill.

It’s no secret: when baseball players are over the hill, two things leave them—bat speed and cognitive speed (see the ball, hit the ball hard). The average professional baseball player retires before they turn 30, even though all of them are STRONGER than they were as rookies. I bet their sprint speeds are nowhere near where they were as rookies. They’ve gotten old and slowed down.

I Thought This Was a Golf Article?

Guilty as charged, but it’s important to see the big picture, too.

This article is really about the central nervous system and its absolute control over the most extreme movement in the human experience: sprinting.

I was having dinner a year ago with Les Spellman and Brian Kula. Les was talking about the undeniable relationship between the CNS and speed. I added my insight that too many people see speed through a muscular lens instead of an electrical lens. Then, Brian Kula told a story that will be forever etched into my brain.

Brian told us about improving the sprint speed of a female golfer and how she consequently improved her club head speed. Hmmm…maybe speed is truly the tide that lifts all boats.

Eleven months later, I wanted to hear the exact story so I could include it in this article. Brian referred me to his right-hand man, Taylor Nelson-Cook of Kula Sports Performance, who worked directly with two female golfers, Elle Higgins and her sister, Brenna Higgins. Both of these girls improved their maximum sprint velocity by a whopping two mph!

Of course, when max speed improves, acceleration improves, too, and it did. But here’s the stunner: their club head speed improved by 15 mph. Elle is now golfing at the University of Montana, and Brenna is at Valor Christian High School, where she was named 5A Golfer of the Year in Colorado.

Elle and Brenna Higgins were not trained as golfers but as sprint-based athletes. Their training was no different than Brian Kula’s training of Christian McCaffrey (who also attended Valor Christian H.S.). At Kula Sports Performance, they do not reverse-engineer sports; they create athletes.

Six weeks ago, I began consulting with Jonathan Ochoa, a golf coach in Spain. Jon has become a disciple of what he calls “Feed the Cats Golf.” Jon has initiated a “Sprint, Drive, Pitch, and Putt” competition with his students. In addition, Jon has started sprinting himself, improving his 40 time from a 5.07 to a 4.89. Jon’s club speed has improved from 110 mph to 117 mph.

Kyle Berkshire is the World Champion Driver. His club head speed is an eye-popping 157 mph (PGA average is 116 mph), his ball speed is 241 mph, and his world record drive is 579.6 yards.

In a 2020 article about his training, Kyle Berkshire listed four things. The most counterintuitive part of his training is, of course, SPRINTING:

“I’m a believer in doing things that allow your body to move at its fastest without relying on mechanics or positions. That’s why I like to do sprints. When you bust out of the blocks, you aren’t thinking about technique. You’re just going. That’s what long driving is all about, too. Release your inner athlete, no matter your age.” –Kyle Berkshire

To understand the freaky athleticism required to drive a golf ball 579 yards, you must check out this two-minute clip. It’s amazing!

What Would Speed Training Look Like?

What if I told you that your investment in speed could be less than three minutes a week?

Whether you’re a soccer player, lacrosse player, rugby player, baseball player, or golfer, three minutes of work in two to three speed sessions a week could do the trick. This is called my Atomic Workout.

Atoms are the smallest unit of matter but are also incredibly powerful. My Atomic Workout is NOT optimal; it’s atomic… the least we can do and still challenge the CNS. If highly organized, you can do the Atomic Workout in 15 minutes, and you will do only 60 seconds of work. Make sure you have a solid timing system. Hundreds of high school football teams have replaced their traditional worthless warm-up with the Atomic Workout.

The key thing here is to develop a sprint habit and stay as consistent as you can, sprinting two to three times a week. Perform the speed drills as well as you can, but remember, it’s the max-velocity sprinting that’s most important. Michael Boyle says consistent sprint training allows the body to “self-organize.” In other words, the body starts to figure things out. As you get faster, your drills will become more fluid. Your speed drills will feed your sprinting, and your sprinting will feed your speed drills.

The key thing with my Atomic Workout is to develop a sprint habit and stay as consistent as possible, sprinting 2–3 times a week. Remember: it’s the max-velocity sprinting that’s most important. Share on XIf you are already pretty athletic and want to optimize your work, you should not do more sprinting (remember, we should only sprint two or three days a week). If you want more work, you should do X-Factor exercises on one or two of your off days. These are exercises that fast people do well and slow people do poorly. The #1 rule of X-Factor work is never to burn the steak.

It takes time to get good at X-Factor work. My freshmen are typically awkward and uncoordinated. By the time they are sophomores, they are good enough to demonstrate for our new incoming class.

Nantes, France

On Monday, December 11, at 6:30 p.m., I will speak in St. Sebastien sur Loire, a suburb of Nantes. My presentation is titled “The Unexpected Benefits of Raising the Ceiling of Speed: From Bodies to Brains.”

My audience will include coaches, cognitive scientists, and sports scientists. The presentation will be open to the public, but you need to register. My presentation will be in English but will be translated into French.

Address:

Maison des Associations René Couillaud

6 rue des Becques

44230 Saint-Sébastien-sur-Loire

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF