I have previously decried the current narrative that exists around training for surfing performance: a type of quasi-preparation with methods plagued by futility and driven by surf websites (and even the coaches of elite surfers). The approach is typical of what we would refer to in our own circles as Mickey Mouse S&C—a bit of a joke. My criticisms are not an effort to fun-sponge and restrain surfing’s essential, free-spirited culture. Rather, my point is to clarify that evidenced-based methods of preparation are what work and provide the potential for surfers to actually have more fun by fueling progression, keeping them in the water and allowing them to have even greater confidence in their abilities.

Due to their low training ages and high surfing frequencies, the development of whole body strength and power would be the appropriate first step in a performance model for surfers. Nevertheless, considering the sport’s intermittent nature and requirement for high levels of speed and fitness, the training of the appropriate energy systems is another critical element.

Typical approaches to this training for surfers range from things that look really naughty, hard, and fast like your classic battle ropes, prowler pushing, and sand sprints, to things that look boring and tragic like swimming endless lengths in the pool with the OAPs (old-age pensioners). Simply, these approaches do very little for replicating the unique demands of the sport. They are void of specificity.

Get creative in trying to make these approaches for speed and fitness development for surfers as fun as surfing. Share on XWhat follows are approaches that work. My challenge to you as the coach is to read this, get out surfing yourself, direct your beaten body in the direction of the shower, and then sit down to get creative in trying to make these approaches for speed and fitness development as fun as what you just experienced.

Speed in Surfing

What’s Happening Here?

Speed (alactic capacity) in this context does not refer to the speed of riding a wave—this is too dependent on a myriad of uncontrollable factors, such as the location’s bathymetry, type of break (beach, reef, point, etc.), and size of the wave. Instead, in this context speed refers to a surfer’s maximal sprint paddling (MSP) speed, ability to change direction (COD), and agility in the water. We know surfing involves a lot of paddling, but much of it is submaximal. All-out MSP efforts account for only approximately 5% of total time in a surf session1, yet they provide a platform for the whole purpose of surfing: riding waves.

Higher levels of MSP and COD allow a surfer to:2

- Catch steeper waves or take off on a more critical area of the wave.

- Have a faster entry into waves, enhancing initial momentum and number of potential maneuvers.

- Reposition, gain a positional advantage over other surfers in the lineup, and better negotiate the ocean.

- Have less chance of potentially getting “caught inside” and taking a beating.

For recreational surfers, the benefits of the above are obvious. For competitive surfers, all of these will maximize the following judging criteria in competitions:

- Evidence of commitment/degree of difficulty

- Combination, variety, and innovation of maneuvers

- Display of speed, power, and flow

How Do We Improve It?

Speed and agility, as in most sports, are central in surfing to both excelling and entertaining. Thus, they should be sought insatiably. Paddling velocity itself is a function of stroke length (meters per stroke cycle) and stroke rate (strokes per minute), and improving either of these technical parameters independently has been found to result in improved speed.3 COD has yet to be studied in surfing, but we know from the research that it is underpinned by MSP and that their mechanical determinants are similar. Thus, to enhance MSP and COD, a combination of typical approaches that are also used on land should be employed with surf athletes:

1. Improve the related underlying capacities in the gym.

For most surf athletes, neural adaptations to strength training should be sought while minimizing hypertrophic adaptations. This is due to a) relative strength being found to be more influential than absolute strength with high force-to-mass ratios desired and b) neural adaptations appearing to be primarily responsible for increases in swimming performance.3 You must take the surfer’s needs into account, but all else being equal, the more propulsive force a surfer can apply in a stroke, the faster their MSP will be. When the upper body (UB) strength standards are in sight, employing exercises across the load-velocity spectrum will ensure the development of other key capacities such as RFD and power.

2. Practice moving fast and changing direction at high speed.

Introducing max effort sprint paddling efforts with long rest periods (with and without changes of direction) over both accelerative (~5-10 meters) and max velocity distances (~15-20 meters) will provide a stimulus absent from most surfers’ regimens and provide novelty to the body in the form of recruitment of fast twitch type II fibers.3 Pitching athletes against each other for a total volume of ~100-125 meters in paired or group “racing” efforts will provide competition and ensure 100% effort. Coupled with improving the underlying capacities, both of these approaches should be the coach’s first port of call.

3. Impact paddling technique.

This could take many coaches down a rabbit hole, but it doesn’t have to. The whole goal is to reduce horizontal and lateral drag in the water.3 You should address bad habits like head rolling (side to side) and slumped posture. A high chest through thoracic extension (“banana” shape) optimizes stroke length and allows a more vertical elbow on entry, providing a more powerful stroke. You should also examine turning efficiency from 45 degrees (repositioning/redirecting) to 180 degrees (turning to then paddle for a wave). Consistently reinforcing technique through simple cues will show gradual improvements in these skills.

4. “Transfer bridge” the underlying capacities through resisted paddling work.

This is a novel method that, to the best of my knowledge, has yet to be researched in surfers. However, it has been shown to have significant effects on performance in swimmers.3 It has also been proven to provide a transfer bridge between newly established capacities developed in the gym and the target task.4 For example, resisted paddling may provide the opportunity to apply newfound UB strength in the relevant intermuscular pattern of recruitment when paddling.

You could add resistance using a band or bungee (you can hold it or attach it to a diving block to the waist of the surfer) or chute (attached to the waist of the surfer). Another option is MSP and COD efforts using very low volume boards (~20-25 liters), slightly increasing resistance and energy cost due to a higher drag across the surface of the water, which may lead to potential improvements in speed on the surfer’s usual board.5 Not dissimilar to resisted sprinting on land, a stimulus of both higher resistance (e.g., using a chute over accelerative distances) and lower resistance (e.g., using lighter resistance band over max velocity distances) could be effective.

5. Reduce fat mass.

Shifting some “nonfunctional” mass is a tried and tested way to aid speed development by reducing resistive forces in the water and increasing force-to-mass ratios. A no-brainer.

Overall, you should implement a combination of these five approaches. Surfers should be reminded of MSP’s importance as a discriminator between different levels of surfers, and that surfers achieving better competition results have been shown to be faster. Dr. Jeremy Sheppard, formerly of the Hurley Performance Centre in Australia, recommends competitive surfers shoot for an MSP over 2.0 m/s.6

You should ideally train and test surf athletes for speed on their board in a standard 25-meter indoor or outdoor pool to eliminate the effects of wind and currents that might disturb training sessions in the ocean. Suggested acceleration (5-meter sprint) and max velocity (15-meter sprint) standards are outlined below, with suitable COD tests yet to be established.

Aerobic and Anaerobic Fitness in Surfing

What’s Happening Here?

The influence of speed on the sport is undeniable, but what use is it if a surfer isn’t fit enough to recover and repeat-sprint continuously throughout a one- to five-hour session? Waves pass unridden (or other surfers take them), they wipeout and get an unnecessary hold-down, they get caught inside by a rogue set, or they can’t complete their maneuvers when on the wave itself. For competitive surfers, the ultimate cost of this is reflected in lower scores and rankings; for recreational surfers, it’s unnecessary disappointment. Consequently, in a sport characterized by repeated high-intensity intermittent paddling efforts combined with multiple continuous endurance bouts, surfers need to have well-developed aerobic and anaerobic capacities.7

The influence of speed on surfing is undeniable, but what use is it if a surfer isn’t fit enough to recover and repeat-sprint continuously throughout a 1- to 5-hour session? Share on XAs discussed, MSP occurs predominantly when paddling into waves and paddling for the outside when a big set rolls through. However, surfers also paddle at moderately high intensities when paddling against currents, wind, and advancing waves or to reposition themselves in the lineup. Low-intensity paddling takes place across longer distances, when paddling out to the “peak” or takeoff zone (where the waves begin to break).

Mean paddling bouts have been found to be ~20-30 seconds, with the majority (~60%) between 1 and 10 seconds.2 Yet, this does not conclude the demands on fitness qualities for surfing. Paddling efforts are interspersed with duck diving oncoming waves and breath holding in wave hold-downs after getting caught inside or wiping out. Coupled with paddling, both of these place immense demands on the surfer’s aerobic and anaerobic abilities due to their hypoxic nature, as well as the potential element of danger. It must be noted that the conditions and type of break will always dictate the intensity and duration of any efforts performed in a given session. Swell size, swell period, wind speed/direction, tides, and currents all determine the work required: Mother Nature calls the shots.

Tynemouth is my home break here in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, and most days it is a breeze to paddle out and duck dive my way to the peak—seven duck dives and a couple of minutes’ work. In contrast, on my last trip to Dominical in Costa Rica, I watched a surfer take just shy of 40 duck dives to get outside and well over 10 minutes to reach the peak. Nearly 40 duck dives is obscene; most surfers would whip their board around and get themselves right back to the beach to try again another day.

As for breath holds when getting caught inside or after wipeouts, these are usually of a short duration (~2-4 seconds) and can be successive. This would be bearable when calm and with a peaceful resting heart rate, but throw in big surf, adrenaline, lots of paddling, a boatload of duck dives, and long session durations, and you can have some severely taxing work taking place.

Recovery periods can vary hugely from session to session, again heavily dictated by the conditions. In some sessions, the surfer can spend up to 55% of total time just sitting on their board waiting for lulls to pass and the waves to surge back in.2 More than half of a session spent sitting stationary can seem like a lot, but keep in mind that typical surf session durations can be outrageous. In other sessions, recovery periods can be very short, and surfers must have the ability to recover rapidly (64% of recovery periods are between one second and 10 seconds).1

It also appears that there are significantly higher work-to-rest ratios at beach breaks compared to point breaks due to the different bathymetry. Further, point breaks involve more low-intensity continuous durations of paddling due to longer rides, whereas beach breaks can see more frequent but shorter high- and moderate-intensity paddle efforts.8

Clearly, from the demands outlined, surfing strongly stresses all energy systems. Share on XThe strenuous actions of paddling, repetitive duck diving, breath holding, and then waveriding provides a melting pot of effects: moderate (140 b·pm-1) to high (190 b·pm-1) heart rates, 6.8 to 8 mmol·l-1 in peak blood lactate, and a total paddling distance covered of 1-2 kilometers in sessions.9 Surfers have also been recorded as having VO2peak values of 44 to 50 (mL·kg·min-1), comparable to swimming.7 This is significant, given the fact that VO2peak tests of the UB are around 30% lower than LB tests (running, cycling, etc.) due to peripheral factors, such as earlier onset of lactate threshold in the lesser muscle mass of the UB, rather than central cardiovascular limitations.3 Clearly, from the demands outlined, surfing strongly stresses all energy systems.

How Do We Improve It?

Before implementing fitness sessions, there are two issues you must consider:

- With access to consistent waves, both competitive and recreational surfers can accumulate some serious paddling volume and fatigue.

- Competitive surfers can often have an intense and unpredictable competition and travel schedule that leaves little opportunity for capacity development.

The physical development of surfers in wave-rich areas can prove much more difficult than those in less consistent areas. These surfers can rack up typical surfing lows of 12 hours per week and highs of 25 hours. This is 8-12 hours of paddling per week. If the waves are firing and the conditions are perfect, 40 hours of surfing per week has been recorded.10 This is roughly 20 hours of paddling in a week!

This is all good fun for a surfer, and the desire to get some decent waves can mask the sheer volume of work. These surfers already perform a lot of specific fitness work. The addition of extra paddling sessions during or following a spike of favorable and consistent surf would be counterproductive and would risk overuse/repetitive injuries by adding unnecessary training load to a surfer already under the grips of fatigue.

The addition of extra paddling sessions during or following a spike of favorable surf would be counterproductive and risk overuse/repetitive injuries by adding unnecessary training load. Share on XConsequently, you must carefully plan specific fitness sessions by chatting with the surfer and tracking surf forecasts. If the area’s waves are firing, surfing will take priority. However, no matter where you are based, there are often distinct seasonal flat spells. In the U.K., summer is often flat on and off for weeks on end—autumn into winter is when the beaches and reefs emerge from their slumber and begin to light up. Summer is then our down season and our primary window of opportunity for the development of physical capacities. Even during surf season, however, there can be times when the waves turn mediocre or even flat and the surfer will spend less time in the water. These lower-volume weeks are the secondary window of opportunity to integrate fitness sessions.

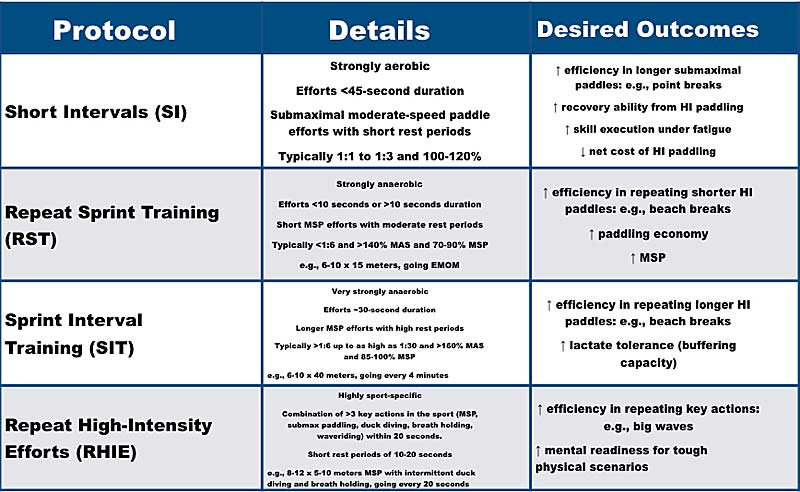

In these windows of opportunity, a lower volume/load and time-efficient approach to improving fitness is practical. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) would meet these requirements, while also replicating surfing’s repeated high-intensity paddle efforts with short rest periods. Buchheit & Laursen have discussed at length the different protocols that you can apply here:11

- Short intervals (SI) have been shown to improve aerobic capacity (endurance paddling) and moderately improve repeat sprint ability.

- Sprint interval training (SIT) (and likely repeat sprint training (RST)) significantly improves repeat sprint ability but does not appear to improve aerobic capacity.12 At first, this is surprising, as you would expect both types of training to more strongly assist one another; but it appears that they provide different physiological adaptations, and this reinforces the need for the implementation of a mixed methods approach.

- Repeat high-intensity effort ability (RHIE), pioneered by Gabbett in the team sport context, should also be considered.13 RHIE may present a highly specific method of improving surf fitness through the inclusion of a combination of key actions (MSP, submax paddling, duck diving, breath holding, waveriding, etc.) with short rest periods, precisely meeting the demands we want. Given that surfers are commonly engaged in such bouts, it is likely to be beneficial.8 However, quite understandably, a RHIE test is yet to be established for surfing.

Coaches can implement the protocols in table 2 with only modest increases in paddling volumes, limiting the training load on a surfer. I would recommend 2-3 times per week in the down season and 1-2 times per week during small/mediocre swells or in transition phases between competitions.

During these transition phases, the selection of an appropriate protocol would be useful. For example, if a surfer’s upcoming competition is at a point break, you could use SIs to prepare them for the longer durations of continuous paddling. For a beach break and small surf conditions, the emphasis could switch to RST or SIT to emphasize shorter, more high-intensity efforts.8 RHIE could act as a tool to prepare for competitions with big waves and the chaotic nature of these conditions (wave hold-downs, crazy wipeouts, and lots of duck diving). Finally, various types of breath-hold work are also a necessity throughout; both when calm and in more taxing situations, e.g., successive duck diving without a breath, resisted swimming underwater, and underwater boxing. All protocols have their place if thoughtfully planned.

Like speed training, surfers should perform both training (table 2 above) and testing (table 3 below) for fitness on their board (and in a pool) to retain specificity. It is tempting to just use swimming for these protocols, but this does not replicate the UB specificity, appropriate body positions, and paddling demands of the sport closely enough. Swimming has its place, but you should consider it more of a method of cross-training for surfing along with classic paddleboarding (alternating arms and double arm), ski erg (seated or standing), and burpee work (into a surf stance), applying the same protocols in table 2.

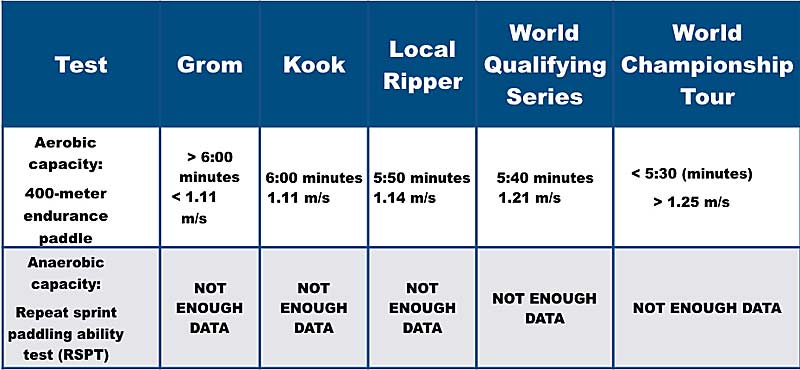

Suggested standards for aerobic and anaerobic fitness are outlined below. For the 400-meter endurance paddle, place two buoys 2.5 meters in from each end to provide a 20-meter distance. The surfer would paddle 10 laps (up and back), turning 180 degrees each time at the buoys. Record the total time, and you can then calculate MAS.

The repeated sprint paddling test (RSPT) would involve 10 x 15-meter maximal sprint efforts, going every 40 seconds. The RSPT would determine the surfer’s total time for the 10 efforts along with the decrement (fatigue index) between efforts (first 15-meter effort minus the slowest effort). A decrease in either of these would provide potential evidence of improved RSA. Unfortunately, however, RSPT standards haven’t been established, as there’s little data in the research.

Make It Fun

Throughout this series, I have tried to sidestep the fluffy BS that permeates surf training and build a performance model based on the available evidence. I have attempted to summarize this model by addressing the big qualities: first strength and power; now speed and fitness.

S&C coaches working with surfers are challenged to not just utilize effective methods of physical preparation, but also convince surfers of a method’s benefits and achieve engagement by making enjoyment the chief objective of sessions. As coaches, we hope that every athlete we work with will be diligent, curious, self-reliant, and coachable. The reality is that most surfers probably don’t like to train. They like to play.

Surfing is the ultimate form of play—and they do loads of it. Waveriding accounts for only ~4-8% of total time in a surf session.3 Yet, if the conditions and waves are right, these could be the sweetest combined seconds of a surfer’s month, year, or even their life.

Exciting and competitive training sessions within a novel program of development can help maximize surfing’s peak experiences. Share on XAs coaches, we aim to maximize these peak experiences. Exciting and competitive training sessions within a novel program of development can facilitate this. If we do this and deliver results, we will contribute to a change in the narrative around surf training.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Tran, T.T., Lundgren, L., Secomb, J., et al. “Comparison of Physical Capacities Between Non-Selected and Selected Elite Male Competitive Surfers for the National Junior Team.” International Journal of Sports Physiology & Performance. 2014;10(2):178-182.

2. Farley, O.R.L., Harris, N.K., and Kilding, A.E. “Physiological Demands of Competitive Surfing.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2011;26(7):1887-1896.

3. Crowley, E., Harrison, A., and Lyons, M. “The Impact of Resistance Training on Swimming Performance: A Systematic Review.” Sports Medicine. 2017;47(3).

4. Brearley, S. and Bishop, C. “Transfer of Training: How Specific Should We Be?” NSCA Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2018;41(3):97-109.

5. Ekmecic, V., Ning, J., Cleveland, T.G. et al. “Increasing surfboard volume reduces energy expenditure during paddling.” Ergonomics. 2016;60(9):1-20.

6. Sheppard, J. “Masters & servants: How the preparation framework serves the performance model.” UKSCA Conference Presentation. 2017.

7. Farley, O.R.L., Harris, N.K., and Kilding, A. “Anaerobic and Aerobic Fitness Profiling of Competitive Surfers.” The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2011;26(8):2243-2248.

8. Farley, O.R.L. “Assessment of Competitive Requirements, Repeated Sprint Paddle Ability and Trainability of Paddling Performance in Surfers.” Edith Cowan University Ph.D. Thesis. 2016.

9. Farley, O.R.L., Abbiss, C.R., and Sheppard, J.M. “Testing Protocols for Profiling of Surfers’ Anaerobic and Aerobic Fitness: A Review. NSCA Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2016;38(5):52-65.

10. Sheppard, J. “HIITing the lip in professional surfing.” HIITscience.com. 2018.

11. Buchheit, M. and Laursen, P.B. “High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle: Part I: cardiopulmonary emphasis.” Sports Medicine. 2013;43(5):313-338.

12. Farley, O.R.L., Secomb, J.L., Parsonage, J., and Lundgren, L.E. “Five Weeks of Sprint and High-Intensity Interval Training Improves Paddling Performance in Adolescent Surfers. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.2016;30(9).

13. Austin, D.J., Gabbett, T.J., and Jenkins, D.J. “Repeated high-intensity exercise in professional rugby league. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2011;25(7):1898-1904.