Athletes can achieve great results by harnessing the power of potentiation and efficiency and applying it to selective ballistic endeavors specifically through the use of such dense, complex training methods in the context of applicable sport movements. Acute, complex, high-density training provides the greatest neural adaptation benefits and allows the often separated qualities of speed and strength to feed on, and benefit, one another.

There are two truly outstanding complex movements that marry strength and speed to take explosive power to its highest level:

- French Contrast

- Potentiation Clusters

In the world of jump training and athletic performance, there’s a lot of talk about complex training. Improving speed helps improve weight room marks. And, when properly performed, weight room work offers strong acute benefits to the explosive coordination of various speed movements.

This article takes the idea of complex training and expands on it in practical and theoretical ways. The recommendations are a plug and play training method that will yield immediate results when performed correctly with a wide range of athletes. (See point #1 in my last article on the impact of specific variability in training.)

I started experimenting with higher density complex models after learning about Cal Dietz and his work in this area, his website www.xlathlete.com, and his book Triphasic Training co-written with Ben Peterson.

I was tentative for a long time about the extended use of denser complex training because of mixed research regarding potentiation, most of which utilizes heavy deep barbell squats as the potentiator. This isn’t the best fit for a lot of complex work, as I’ll explain later. But because of Cal’s work, Frans Bosch’s book Strength Training and Coordination: An Integrated Approach, and plenty of time to experiment over the years, I now view training as a coordination and movement puzzle. The proper use of complex and stacked training is a key to solving the puzzle and induces better performance.

Jump training is a coordination and movement puzzle. Share on XClearly, many track athletes have been successful without traditional complex training using barbells. But how many of these track athletes played a team sport as part of their training histories, such as football, basketball, soccer, or volleyball?

Many coaches and athletes don’t think of team sports as complex training for skill acquisition. Playing a pickup game of basketball, however, delivers a big stimulus for multi-directional movement demand, coordination, and enhanced efficiency under fatigue. In the course of a training or practice session, athletes generally wait until after a few pickup games before trying to do dunks. Most of my trainees have been at their highest performance level after a few pickup games.

Explosive coordination loves the skill mash-up of team sports play. Share on XExplosive coordination loves the skill mash-up of team sports play. I believe coaches can use the team sport coordination principles under the potentiation umbrella found in resistance training and combine them with the reflexive power of plyometrics to further enhance explosive speed performance.

Ideas from the World of Powerlifting and the Real Mechanism of Dense Power Training

Over the years, I’ve had an up and down relationship with complex training. The research surrounding the concept doesn’t support using it in a program unless there is a lot of extra time to kill.

It takes about ten minutes for the potentiation effect from a heavy weighted exercise (85 to 100% 1RM) to truly improve a ballistic movement like a vertical jump, according to most papers. With modern programming, it’s hard to find a specific protocol that uses this recommendation. Many coaches use post-activation potentiation training to sell their programs, but based on the science, the training doesn’t work, at least not acutely.

Density and Speed Considerations

When we look at training speed, we generally think of running timed fast 150’s in spikes with 8 to 15 minutes of rest in between. Running fast with full recovery is a premier way to build track speed. But this high rest method isn’t the only way to build speed and power, especially for movements that have a little longer contact times, such as jumping.

I’m a coach who’s been typecast as the plyometric guy, the arena where I have the most distinction based on much of my work. My day job is a university strength coach, and using barbells to improve athletic performance across a variety of team settings is important to me regarding the total development of athletes.

There has been an exodus from overemphasizing performance levels in general preparatory exercises (squats, cleans, bench, etc.). I’ve been a strong proponent of this in the last few years, but I think it’s unwise to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Shying away from the powerful benefits of properly selected and coached barbell training will leave gains on the table for many athletes. Barbell training can deliver the coordinative mechanisms seen in the expression of powerful movements, such as jumping and sprinting.

Barbell training delivers the coordinative mechanisms expressed in powerful movements. Share on XAnecdotes from the Barbell World

Olympic weightlifting coach Glenn Pendlay recently posted an article about the power of training density for bringing up a lagging deadlift as well as Olympic lift performance: “The Holy Grail of Sports Training: EMOM Sets.”

Pendlay talked about his experience with powerlifting coach Louie Simmons, who recommended a high-density workout to bring up Pendlay’s lagging deadlift by doing small repetition deadlifting sets every minute on the minute (EMOM) over many sets.

Why would Simmons recommend EMOM training to bring up the deadlift in particular? Doesn’t high-density training build endurance rather than power? Typically, yes, but when utilizing strength exercises (and even contrasting forms of speed), the story can be different.

By the 7th or 8th round of an EMOM deadlift set, something strange happens. The weight starts to come off the ground much faster as if the brakes have suddenly released.

Of all the lifts, the deadlift requires the most mental strength. This means athletes generally lift a smaller proportion of what they’re physically capable of compared to other powerlifting movements. After all, we don’t hear of mothers squatting the house to save their child, but rather pulling up their car! (Perhaps a poor anecdote, but I do strongly believe pulling strength, in particular, has very high untapped reserves compared to other lifting movements).

Perhaps this phenomenon is due to a high risk of injury or because the bar must start from a dead stop position or a combination of these and other factors. Regardless, a very strong mental drive is required to pull the bar from the ground.

What does this have to do with the use of EMOM work in bringing up the lift? Coaches don’t know exactly why EMOM training works (even researchers don’t have this pinned down), but we strongly suspect it has to do with the gradual potentiation of prime movers and a significant reduction of antagonist muscle activity.

We do know, through the research, that any potentiation likely occurs in the fast-twitch fibers. This alone makes high-density training important to improving the rate of force development. Whatever combination of factors improves lifting power and efficiency, it’s the nervous system’s role that leads to better performance.

Overview of Denser Complex and Skill Acquisition Methods

Rather than looking at potentiation from the standpoint of gross motor unit recruitment, such as the relationship between deep squatting and standing vertical jumping, look at it from the standpoint of skill stacking in a circuit-based form of motor development learning.

French Contrast helps improve the motor variability of the total training effect. When we feed the nervous system with subtle differences and perturbations in typical training patterns (such as performing wicket drills with offset mini hurdles or sprint stride drills with uneven pieces of tape), we create a nursery of new improved motor patterns and athletic potential. French Contrast uses both potentiation (improving the availability of the motor pool) and variability (which improves coordination and skill acquisition) to build a better total pattern.

The Million Dollar Workout developed by Chris Korfist and Dan Fichter is another great method that stacks one specific sprint exercise with three supportive skills. Athletes can get really fast, really quickly with this method, which I learned at a Speed Football Consortium. It’s an impressive training method, and my clients have gained great results with it.

I’ll use a quick anecdote from my high jump days as another example of acute coordinative effects. On any short approach day, I performed 8-12 short approach high jumps using 3-5 steps. If I immediately followed the short approaches with a full approach and jump, my penultimate step mechanics and coordination were horribly distorted in favor of the 4-step jump. I would go straight into the bar rather than up and over.

The human body will warm itself up and align itself for whatever skill is being worked. If you perform 5 sets of 8 deep squats and then do a vertical jump, the jump form will imitate the biomechanics of the squats you just performed before you got under the bar.

If we work on a skill one-dimensionally, we’ll create results for that dimension. If we bounce between two or more complementary skills, we’ll end up with a higher and better-rounded level of performance. The better the coach is at selecting the skills, the higher the improvement in performance.

This training concept is heavily used by many current swim coaches. Sets revolve around many circuits of stacking skills, portions of strokes with various emphasis, gear-based swims, cruise-speed swims, and then hard swims. Different strokes can be used to potentiate an athlete’s main style of stroke and enhance their coordination range.

Below is an example of a common swim circuit for sprinters. Much of it is a foreign language to us track coaches, but we can clearly see the concepts of improving coordination and building robust swim patterns.

Sample Swim Sprint Set

- 4×25 with a swim parachute

- Odds: kick to 12.5, swim from 12.5 to 25

- Evens: scull to 12.5, swim from 12.5 to 25

- #1+2 steady effort, #3+4 stronger effort

- 2×50 no parachute swim, build to a strong effort

- 4×25 with fins #1+2 kick to 12.5, swim to 25, #3+4 swim fast

(Note: a standard short course pool is 25 yards long so many portions of sets will be halfway or 12.5 yards.)

Swim is a sport that is built more toward the “art” end of the “art and science” spectrum. This is appropriate because moving in the water is more intuitive, subconscious, and feel-driven than any other athletic movement. In various sports, there may be cases where strength can overcome technique, but you can never fight the water since everything must come within the scope of the technical model.

In this technique and feel-driven routine, it’s no surprise that set diversity and complex skill training has become common practice in swim training sets. I believe land-based sport coaches can learn from this workout approach and apply it to their own programming.

French Contrast: Nuts and Bolts

French Contrast training, in my experience, is one of the fastest ways to build vertical jumping ability in athletes. I’ve regularly seen four-inch vertical gains in one training session. It’s also a great method to realize an athlete’s existing strength in the form of vertical jump and acceleration improvements.

Regardless of the exact science, French Contrast works acutely and chronically. A French Contrast session looks something like this:

- Heavy partial range lift or isometric for 1-3 reps

- Rest 20 seconds

- Force oriented plyometric exercise, such as a depth jump

- Rest 20 seconds

- Speed-strength oriented lift for low to medium reps, 2-5 typically

- Rest 20 seconds

- Speed-oriented plyometric exercise of higher repetition range

- Rest 2-5 minutes and repeat

First French Contrast Movement: Big Strength

The first exercise in the French Contrast circuit is a big strength movement which activates as many relevant motor units as possible based on the ultimate movement outcome of the French Contrast circuit.

This strength movement can be a traditional up and down lift or an isometric, depending on the outcome goal. If you’re building a training phase, it may be better to use standard lifting reps for their hormonal and muscle building effects. For more of a realization effect that maximizes the speed end of the complex, I recommend using partial range, or isometric, work such as an isometric half or quarter squat hold for 3-7 seconds.

Several years ago, jumps coach Mike Goss told me of an interesting study that shows the effects isometric movements can have on potentiation. Using weights on a softball bat to warm up harmed unweighted bat speed. Conversely, athletes who performed 3×5 second isometric reps pulling a bat handle against an immovable resistance in a specific batting position significantly improved their bat speed for a 2 to 12-minute window. This also shows us that isometrics allow for potentiation in a shorter time frame than the 10 minutes we commonly see cited in the research using deep squatting for potentiation.

This idea opens a door for many creative variations of isometric movement that have relevance to a variety of sports skills. Isometrics also help with safety. When working with large groups of less experienced athletes, an easy way to achieve overload is to perform isometric positions. There is much less that can go wrong, and the athletes must focus much harder on achieving the correct position and muscular tension.

For circuits emphasizing vertical jumping, or knee-based movement, a squat (either traditional or isometric) is the optimal first exercise. If the program’s emphasis is on sprinting or bounding, a hinge movement is a good first exercise, such as a trap bar deadlift from blocks. I find it less useful to use isometric exercises for hinge strength simply because of the strain factor. An isometric back extension or good morning, however, are viable options.

The list below gives good leadoff exercises to potentiate and widen the relevant motor pool without inducing too much fatigue. These exercises are typically 60-90% of an athlete’s maximal effort and are performed for 1-3 repetitions or 3-7 seconds of isometric.

Hinging/Sprinting/Bounding

- Trap bar deadlift from 2-8” blocks

- Isometric back extension (heavy)

- Isometric good morning (bilateral or staggered)

- Regular deadlift

- Concentric only deadlift

- Power clean from the floor

Squatting/Jumping/Vertical Force

- Isometric quarter squat

- 1/2 or 2/3 partial squat

- Split stance partial squat from a rack start

- Partial squat from a rack start

- kBox ½ squats

- Deep squats (accumulation phase)

For squats, I often avoid deep squatting for two reasons. First, the depth of the movement leads to firing patterns that don’t blend well with most athletic movements occurring in a significantly lower degree of knee bend. The coordination is just too different.

Second, the lengthening and loading of the quadriceps muscles create too much local fatigue and coordination disruption to optimize the rest of the French Contrast prescription.

I do believe that athletes who are capable of good technique can use deep squats for the leadoff training exercise, but I consider this a method more for eliciting an accumulation cycle training effect on a muscular and hormonal level, not a realization cycle for neuromuscular improvement. Either option is viable if the coach knows where they are headed with it.

Second French Contrast Movement: Heavy Plyometric

The second exercise in the French Contrast is a heavier plyometric exercise with relatively longer ground contact time. The contact time should remain within the scope of the specific movement the athlete is trying to improve. This movement also has strong potentiation qualities. Some of the easiest jumping I’ve done and seen in my career has occurred a few minutes after several sets of challenging depth jumps properly performed.

Below are some sample options for this portion of the French Contrast workout. Jumps are done for 2-4 reps and bounding or resisted sprint work for 10-20 meters.

Hinging/Sprinting/Bounding

- Bounding

- Multi-jumps

- Repeated standing long jumps/bunnies

- Resisted sprints

- Hinge-based jumps

Squatting/Jumping/Vertical Force

- Depth jumps

- Hurdle hops (higher hurdles relative to maximal ability)

- Rapid box hops (on a higher box, 12-18”)

- Box jumps/seated box jumps

Third French Contrast Movement: Explosive Strength

The third portion of the French Contrast is based on an explosive strength. This includes all the Olympic lifts and their derivatives (in the 50-60% 1RM range) as well as simpler explosive lifts such as jump squats.

When performing Olympic derivatives, the most helpful movements for the circuit’s total effect are those performed from the hang or block position. Going from the floor, however, can be done by athletes who can achieve clean bar speed easily. Again, these exercises are generally performed with 50-60% 1RM range, but this can sway a bit in either direction due to the nature of the movements. Rep ranges are 2-4 repetitions.

Due to the higher bar speeds in this portion of the circuit, it’s more acceptable to perform lifts that incorporate larger ranges of motion in all phases of training.

Below is a list of appropriate movements for explosive strength.

Hinging/Sprinting/Bounding

- Hang clean

- Hang snatch

- Kettlebell swing/lumberjack (depending on whether you are in the Poliquin camp)

- Speed deadlift

- Single leg hang clean/snatch

Squatting/Jumping/Vertical Force

- Speed half squat with bodyweight, or less, on the bar

- Push jerk

- Drop snatch

- Hang squat clean (full catch)

- Rapid deep or partial squats with anchored feet (pull into the bottom)

- Jump squat

- Jump squat from bar resting on pins

Fourth French Contrast Movement: High Speed or Overspeed

The final exercise in the French Contrast is based on high speed or even overspeed movement. This includes band-assisted jumps and any plyometric exercise where an athlete uses ground contacts equal to, or less than, what they experience in their specific jumping or speed-based skill in their sport.

There are cases where I might use versions of this list in both the 2nd and 4th exercise slots of the French Contrast series, particularly with track and field athletes rather than athletes who rely on a greater use of ground contact in their sport, such as football.

Below are some examples of this portion of the circuit.

Hinging/Sprinting/Bounding

- Short contact bounding

- Ballistic throws/multi-throws

- Overspeed sprinting (on an apparatus like the 1080 Sprint)

Squatting/Jumping/Vertical Force

- Rapid tuck jumps

- Speed box hops (shorter box)

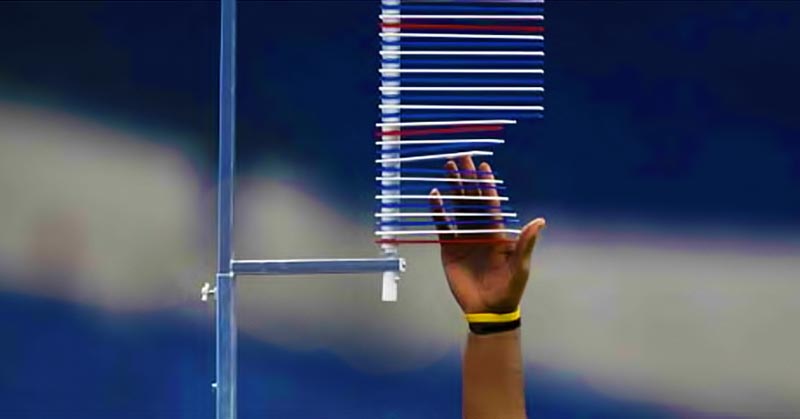

- Assisted jumps with a band and cage or assisted apparatus

- Drop jumps from a lower box (preferably with some sort of ground contact measurement/feedback)/li>

- Hurdle hops over lower hurdles with generous spacing

Sample French Contrast Workouts

Here are some examples of how the French Contrast’s influence on potentiation, coordination, and motor learning can occur in an actual workout. This article emphasizes this aspect of training since currently there aren’t many “nuts and bolts” articles available.

Here is one of my favorite Squat Pathways of the French Contrast sessions:

- Heavy ¼ squat ISO hold, 5 seconds

- Speed box hop x 3-5 reps or depth jump x 2-4 reps

- Speed half squat or anchored deep squat x 3-4 reps

- Assisted vertical jumps x 4-5 reps

Along the Hinge Pathway, I enjoy this circuit:

- Heavy hex deadlift from blocks x 2 reps

- Standing triple jump x 1 rep

- Clean from the hang or floor x 2-3 reps

- Vertical overhead or overhead back shot throws x 3-4 reps (light weight)

In the videos below, Paul Cater of The Alpha Project in Monterey, California, demonstrates a circuit of both the squat and hinge pathways.

Video 1: French Contrast

Video 2: Hinge Pathway

Throughout this training session, Paul added 10cm (4”) to his vertical jump as he moved through the French Contrast circuits. This is a typical gain when correctly performing this training.

For those who are in the specialized camp and want to go SPE on the circuit, perform a program similar to the following for sprint speed:

- Heavy ISO back extension x 5 seconds

- RDL/hinge jumps x 3-4 reps

- Explosive back extension with 50% 1RM x 3-5 reps

- Vertical overhead shot throws x 3-5 reps (light weight)

I perform 3-6 rounds of French Contrast, or possibly more if “the pan is hot.” I like to take 4-6 minutes between each round to test vertical jumps on a jump mat, especially in circuits that emphasize the realization of motor skills. It takes about 2-4 minutes after each circuit before fatigue subsides enough for the test to be a good one. Typically, vertical jumps will increase by an inch per round for 3-5 of waves of French Contrast before leveling out.

Vertical jumps will increase an inch per round in 3-5 waves of French Contrast. Share on XFrom an absolute physiological perspective, potentiation is simply another way to warm up. It’s a very effective way when correctly performed. Squats will warm up an athlete to jump, but most of my athletes say a game of basketball warms them up much more. As mentioned, basketball has a wide variety of explosive movements (random motor learning) packaged in a format with enough training density to have the central nervous system firing on all cylinders.

French Contrast is a modest way to take this concept and alternate between high force and high speed in an approach that accomplishes the same goal in a more controlled manner and delivers a more precise training effect.

Potentiation Clusters

Potentiation clusters are another great method to induce potentiation, coordination, and density-based gains. Potentiation clusters are essentially complex training done in the EMOM style.

To perform a potentiation cluster, simply pair up a low rep strength exercise with an explosive exercise and perform them in a relatively high-density format across 8-12 sets. This is complex training performed in a very specific fashion that optimizes neural adaptations.

An example looks like this superset:

- 12×1 cleans from the floor, starting at 55%1RM and working up to 80%

- 12x20m speed mini-bounding, progressing from speed contacts to maximal distance bounds

- 60-90 seconds rest between circuit exercises

Any strength exercise can be used, but I’ve had the best success with Olympic lifts and moderate to heavy barbell step-ups onto a 10 to 12-inch box. Selective isometrics could also be worked into this method.

I also like simple, and still very effective, supersets of 1-2 cleans with a single rep multi-throw (if space is available). Anything from the “strength bucket” will do.

The speed exercise can be drawn from a wide pool, depending on what we’re trying to improve. For potentiation clusters, I enjoy bounding the most. I’ve found that the more reflexive the speed exercise, the better; perhaps because there is more reflex improvement as opposed to a more static exercise like a seated box jump.

With that, here is a more detailed example of what this cluster might look like:

90-second rest between all exercises

- Power clean from the floor: 1×55%

- Speed-contact alternate leg bounding x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×57%

- Speed-contact alternate leg bounding x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×60%

- Speed-contact alternate leg bounding x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×62%

- Speed-contact alternate leg bounding x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×64%

- Speed-contact alternate leg bounding x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×62%

- Speed-contact alternate leg bounding x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×64%

- Speed-contact alternate leg bounding x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×66%

- Speed-contact alternate leg bounding x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×70%

- Speed-contact alternate leg bounding x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×74%

- Alternate leg bounding for distance x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×77%

- Alternate leg bounding for distance x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×80%

- Alternate leg bounding for distance x 15m

- Power clean from the floor: 1×73%

- Alternate leg bounding for distance x 15m

Video 3: Potentiation Cluster

One of my tricks is to set the tone of the 12-round series with speed-oriented, quick contact movements, hence the low %1RM for the cleans, and emphasize speed contacts in the bounding. The last 3 or 4 sets of a 10-12 set routine transition to more force and longer contacts.

When transitioning to heavier relative weights and faster contacts during the last few sets, an athlete will carry both the potentiation of the previous clusters and the coordination pattern of fast force development (similar to the 4-step high jump versus the full approach example). This helps to improve reflex actions and work muscles at their optimal length and tension levels for maximal speed.

When using potentiation clusters, it’s helpful to use a velocity-based bar tracking method to help motivate athletes toward higher rate of force development in the lift.

Conclusion

Before last year, I considered this training method only useful in the “realization” phase of training since it’s based on improving an athlete’s neural efficiency. Now, however, I realize this method is much more than icing on the cake. Instead, neural efficiency and optimized coordination are the cake. At the least, it’s a very important part of the main training blocks. We want to optimize neural patterns and have an athlete’s physiology adapt to those patterns, not the other way around.

This is the last article of the three-part series on the plyometric workouts I’ve found extremely useful to build explosive power in both track and field and team sport athletes. It marks the culmination of fifteen years of trial and error on my part, and I hope coaches find these principles helpful in developmental programming.

Please check my website Just Fly Sports for updates on my upcoming book Speed Strength, which explores the best methods to build strength within the context of explosive speed development.