[mashshare]

The third part of this three-part review covers more information about the clean, jerk, and snatch lifts based on a series of discussions I had with one of the finest strength and conditioning coaches in the U.S., Al Vermeil. This article is not an interview, but it covers what was discussed on a series of phone calls. If you did not read the first and second articles, you can benefit from reading this part, and we also recommend you start from the beginning of the series.

While this is an article series on the exercises (clean and jerk, snatch, etc.), it’s also a philosophy of getting back to the essentials and doing things right. This is a long article series, but the information is deep and worth reading a few times over. The juxtaposition between old-school training and cutting-edge science is, frankly, some of the best information I have picked up in years, and I am sure you will benefit as well.

Is the Force-Velocity Spectrum Useful or Glamorous?

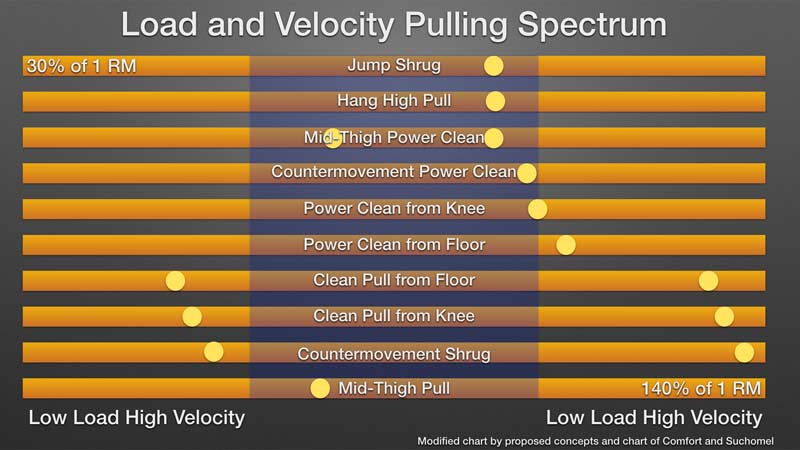

It’s not a secret that I have a deep respect for the load-velocity and force-velocity relationships, and the extensive work done on the weightlifting derivatives was a gem of an article. Since I enjoy and value the work of Jason Lake, I will be critical not of the study, but of the interpretations that seem to stray from the intention of the research. The issue I have is that you don’t have to surf the wave of barbell speeds to develop an athlete. The NSCA guide on the topic is a great read, and it addresses the available and hypothetical information necessary to draw conclusions.

My concern is that the application is less clear outside common rep and set prescriptions in the document. Does using a clean from the floor versus the blocks make a big difference if the force-velocity profile is higher or lower? I think it matters from a tactical perspective and this is where I see the most controversy. Please give me time to explain.

While an athlete who has trained at a high level since high school may find weightlifting a little dry after a decade, high school kids don’t need variety—they need focus. Share on XIn no way am I proposing that variation is unnecessary, but the quest to add derivatives without purpose is common when coaches are programming. In fact, a program that employs accessory lifts and is more holistic with additional exercises helps weightlifter athletes. It seems that after 10 years, coaches are the ones getting stale, not the athletes. While I may agree that an athlete who has trained at a high level since high school may find weightlifting a little dry after a decade, high school kids don’t need variety—they need focus. In my opinion, coaches should think of two elements from the force-velocity manuscript. They are:

- Do the benefits of partial exercises simply imply that they outweigh the more technical full lifts?

- Will the impact to performance be significant when using the load and force-velocity profile qualities of the exercises?

Technically proficient lifters are valuable to coaches, so don’t just see training as a means to an end. Coach them like they are competitors in different sports outside of what they specialize in. Take it seriously! When an athlete is skilled in the weight room, the information available provides a window to system changes that may be harder to pick up in other areas in practice. While strength coaches may be familiar with technical factors inside the sport, they need to go where they are more knowledgeable—the training exercises and tests within their professions.

I see a lot of good coaches that can coach sprinting, but with practices having so little opportunity to train like great athletes instead of participants of their respective sport, it’s better to think what can be gleaned from inside the confines of the performance area. Thus, simpler exercises with less unnecessary movement variability offer an opportunity to improve monitoring and testing of athletes. If an athlete can have technical proficiency with a derivative, which is arguably a less-demanding exercise, then we have something to work with.

You shouldn’t have everyone do the full lifts—but you need to be able to coach the full lifts and accessory exercises before knowing what to remove. Share on XLike the catch, don’t start stripping off the exercises early as eventually you won’t have anything to work with. Al Vermeil repeatedly said (like I may be) that you should not dumb down or strip away exercises too quickly. I see a lot of bad-looking jump shrugs and clean pulls by coaches who feel that the full lifts are too demanding, but the partial movements still look like they need work. It’s not that you should have everyone do the full lifts—it’s that you have to be able to coach the full lifts and accessory exercises before knowing what you can remove.

Somewhere between loaded jumps and the power versions of snatching and cleaning are derivatives, where coaches feel like removing the catch and just working on components of the lifts as prime exercises. The issue is that truncating should be done as an option after you can do the full training movements, not as a way to prune what is incorrectly perceived as unnecessary. The “Bruce Lee” hacking away of what is not essential that is often quoted by coaches does sound good on paper, but who decides what needs to go and what stays for the rest of us? Each decision is internally a free choice, and we should stop punishing or pointing fingers at those who find value in keeping what others left on the cutting room floor.

A very fair point Al Vermeil spoke about during the calls was just training hard and resting smart, and I think the results of his periodization scheme have more influence on the force-velocity profile of athletes than exercise selection of a narrow range of speeds. Coach Vermeil had a few loading schemes, especially the “two weeks hard one-week unload” that really seemed to be a staple.

We should stop punishing or pointing fingers at those who find value in keeping what others left on the cutting room floor, says @SpikesOnly. Share on XI conjectured that it’s likely more potent to hammer for two weeks and rest then hit any specific velocity unless an athlete is exceptionally strong. It’s not that the spectrum proposed by Lake, Suchomel, and Comfort isn’t important, it’s that it’s easy to focus on the science and forget about those who are ignorant and getting results from training heavy and hard. Don’t use the force-velocity profile of an athlete or exercise to load lighter with cleaning or snatching; use more plyometrics and sprinting and still go heavy.

Now comes lifting above and below the knee, either from a hang or from blocks. Privately, Vermeil shared videos of athletes ranging from 6’9” to 7’1” lifting with very large ranges of motion with very little modification to the exercises. Cleaning from the floor, or with small elevations, and squatting deep as the joints will allow them are bread-and-butter exercises. Obviously, not all athletes can start low or get low, but if they can, don’t settle for what seems to be easy. When you see what is possible, your perspective of what is truly hard changes from difficult to perhaps normal.

The elastic contribution is very difficult to model in the research, but if the joints are pre-loaded properly, the leverage and stretch reflexes accelerate the bar later in the movement. Vermeil was adamant about not losing tension and the advantages to pulling below the knee. I personally snatch above the knee from blocks for RFD, but if I want to maximize athleticism, pulling from the floor has advantages you must consider before truncating parts of the moment. Coaches cutting out parts of the lift because they can’t coach it is fine (coach what you are able to do), but eventually you need to be able to coach the lift in its entirety.

One final lesson about barbell speed and athlete speed: It’s a lousy point to talk about how fast an athlete is running and how it relates to the weight room. Yes, horizontally an athlete running 10 m/s and lifting at 1-2 m/s with weight-lifting exercises isn’t worth exploring. The athlete’s neuromuscular system has general qualities that benefit from general training, and unique qualities that can be fostered by higher speeds. An athlete can respond well from performing double-digit sets of cleans, but the same intensity with squats would be problematic. Coaches who care about barbell speed are really focusing on performing the exercise properly, not expecting a fast snatch will make a sprinter reach higher peak sprint velocities. Surfing a narrow part of the curve is not short-sighted; it’s just making sure you own the responsibility of doing the exercises right.

Regarding the article by Jason Lake and colleagues, what I walk away with is that each lift has characteristics. However, the combination of all training elements should be included when interpreting the barbell data. The classification was great taxonomy, but from a prescription viewpoint, the continuum is still rather narrow compared to sprinting and maximal strength, including other forms of power development. Using the outline can help coaches ensure their program starts off right, but you still need to train with some sweat and tears. I learned from Al Vermeil that selecting exercises is about knowing how to adapt to what you see in training.

Should We Care About Bar Path with Athletes?

The final topic with Olympic lifting is barbell path and what it means to a coach in sports. A good answer begins with real-world challenges such as tall basketball players, derivatives, and muscle recruitment. Otherwise, bar path is interesting but not something to rely on to get athletes better.

Years ago, I made a plea to focus more on barbell path and stroke distance, but my main arguments seem to lose their bite because I wasn’t as straightforward as Al Vermeil. One of the best discussions on adjusting barbell exercises and coaching to tall athletes was the presentation by Brendon Ziegler about 10 years ago. For about an hour, Coach Ziegler explained his program and shared video evidence of getting the job done. Watching heavy cleans pulled and caught from the floor by centers in elite college basketball was humbling. To this day, it was the best coaching I witnessed on the lifts and it inspired this section.

Bar path falls into place when you take care of everything around the trajectory of the lift, and over time the loads go up. Don’t underestimate work or volume, as intensity is fine but eventually stagnation or plateaus occur when variables are overly constrained. Several coaches will remind athletes to keep the bar close to them, but what separates good from great lifts is the way they keep the bar close and the speeds they are able to achieve later. Coaches should use the bar path as a way to monitor growth, not to coach or provide feedback as it’s overkill. Someday I think software will be able to do a great job giving feedback that is more specific than showing current and past bar paths, but I worry that raw images alone may be misleading.

Coaches should use bar path as a way to monitor growth; not to coach or provide feedback, as it’s overkill, says @SpikesOnly. Share on XThe general benefits of knowing bar path is it represents the barbell trajectory with both effective and efficient lifts. Athletes who are efficient will take advantage of their anatomy and recruit their body more safely and get more transfer out of it. Some strong athletes get impressive numbers early, but tend to stagnate later when bad habits catch up with them.

The purpose of knowing the bar path is to facilitate a combination of two goals: maximizing the expression of the load and safely improving. Analysis of the bar path is complicated, because each athlete has their own signature that you should evaluate before you start to tinker around. In my experience, bar path is a result of seeing the whole picture and it usually misses most of the idiosyncrasies. Bar path is valuable, but you need to know what to look for and what to accept as just part of the job of pulling a bar.

The loads and bar path of elite competition lifts and those that athletes use in training are clearly obvious to Coach Vermeil. We talked about how and where in the pulling motion an athlete will likely receive the bar. While we didn’t talk about the subtleties too much, it was a point we had to discuss because of the whole bar catch debate. While he cares about the barbell path, he cares more about what the athlete does before and after catching. Coaches should realize that athletes in sport use the weight lifts to develop and maintain power, not to just try to raise their numbers up arbitrarily.

Using barbell path and a force plate, you can see far more of what the athlete is doing than with just the eye. Conversely, you need to know where you should look and what you should not worry too much about. For example, the starting position is huge in track sprints, similar to the starting position in weightlifting. Both positions are static at first, so you don’t need to be especially gifted with coach’s vision to help an athlete.

Al Vermeil shared that an athlete being tall is an excuse coaches give for poor skills in the weight room. While I respect adjusting a training program to those with outlier proportions, being tall is sometimes a way for coaches to make things easier in the short run. He didn’t mince words and reminded me that he simply believes many of the current problems in strength and conditioning come from a lack of coaching skills or an inability to teach when things are not easy.

In our discussions, Al Vermeil praised high school #coaching as the ticket to teaching and coaching development, says @SpikesOnly. Share on XAnd he is right. We are better at identifying the problems we face and making excuses than we are at just getting the job done. Over and over again, he praised high school coaching as the ticket to teaching and coaching development, and this was especially humbling because he has rings from both the NFL and NBA arenas.

Video 1. The future will be about how muscle recruitment, barbell path, joint kinetics, and joint kinematics interact with athlete power. Coaches should think about video analysis software that provides convenient ways to analyze the lifts so athletes can learn how their lifts are trending.

An issue with the research and the many articles I have read is that they don’t offer much practical take-home advice about bar path. It seems that tracing the trajectory of the bar is easy, but doing something actually worth talking about is far harder. In a random internet search, I stumbled upon a great summary—perhaps the most elegant one I have read on bar path. Jacob Howenstein, the owner of Engineered Athletics, brilliantly broke down the American record in the snatch by Jared Fleming. In his article, he covers three refreshing metrics we should arguably think about more than the trace pattern.

- Total distance compared to athlete height (%)

- Time to max bar height (seconds)

- Horizontal displacement summaries (cm)

Of course, the question is what to do with that information, and we need to appreciate that bar speed is overly simplified with readings on Tendo or other VBT tools. I have fought for years to recognize bar path, as it’s the easiest metric to show incompetence in the Olympic lifts. Sure, an athlete may look bad in a lift on a video, but why is a different story. That why is bar path.

It’s not that better technique enables the use of heavier loads; it’s that heavier loads done right teach better muscle contractions, says @SpikesOnly. Share on XCoaches who focus on a load, or even a ratio of body weight to barbell weight, without respecting the path of the bar are simply missing out on key benefits of training with the weight lifts. It’s not that better technique enables the use of heavier loads; it’s that heavier loads done right teach better muscle contractions. The use of the distribution of phase percentages is tricky, but here are a few hints.

-

- Keeping the bar close to the body starts with the first pull and setup. Nearly half of all errors I see with intermediates stem from the posture selected.

-

- Getting tall (not jumping) and not allowing a rocking motion or other horizontal cheating motion improves muscle recruitment.

- Posterior chain strength, from the neck to the calf, enables the lifter to accelerate from a dead start all the way up nearly 2 meters per second with heavy loads.

Other coaches who are more proficient in teaching the lifts have valuable insight, but I have learned more about weightlifting from coaches who work with athletes, not just weightlifting competitors. To polish the craft, work with U.S. weightlifting coaches to be more effective and proficient when starting out. You will need to keep the learning process more integrated by observing coaches who work in bad situations and still teach the clean and snatch.

If you understand bar path in the competition lifts and can teach them, you will find squatting and pressing easy. I highly recommend spending a few years working or training at a weightlifting gym and paying your dues. Sometimes it stinks to spend Friday evenings grinding away at things, but if you want to grow, you can take an easy path to get there (pun not intended). Reps are essential and even if you have the hours and years under your belt you can still improve.

Final Thoughts on Weightlifting

Be loyal to your athletes and the scientific process. Without good research or good record-keeping, good art might be well-intentioned, but could have bad planning and compliance. Don’t ever believe that weight training is either a mystery or super simple—it’s likely somewhere in the grey area. We don’t know everything about training, but we do know enough to make reasonable conclusions, like why some training works and why some methods need to go away.

Don’t wait for others to tell you what to do: Spend some time looking at your training and then ask the hard questions and see if you can solve them. I learned a lot from those few hours on the phone with Al Vermeil, but four key lessons stuck in my head. They are:

-

- Don’t make excuses or try to sound smart for poor coaching choices, just coach better. When coaches start removing parts of an exercise or an exercise altogether because their experience is poor, it’s on them.

-

- Reinventing the wheel is popular, but stick to what works and hammer away instead of trying to be unnecessarily innovative.

-

- Each athlete is different, so make adjustments. Don’t get caught up with a system, but focus on what they can do.

- The clean and snatch are awesome tools and have unique assets that coaches should take advantage of if they can.

Coach Vermeil didn’t hide his opinions of the current state of strength and conditioning. He was right about a lot of issues, especially the number of jobs that are available without qualified coaches. Nearly all of the great strength coaches in the past came from physical education; now, sport science is the degree being pursued. He is concerned about coaching groups, as many coaches can’t even instruct athletes one on one, let alone in groups.

Again, Coach Vermeil reads research, and sends studies he thinks can help the field out to his email list, so don’t think this is a bash of the science. It’s just that sport science without teaching is not coaching. He added a few comments and the history of his program with the following:

“When I was at Moreau High School, our program consisted of basic strength exercises: squat, press, pulls, Olympic lifts, plyometrics (thanks to Don Chu), and sprint training. We also incorporated change of direction circuits—it not only developed change of direction capacity, but anaerobic endurance. We did not have bumper plates and lifted on the second floor, so we had to lower the weights and we weren’t allowed to drop them. This developed great eccentric strength and helped our Olympic lifting technique, because when you do things in the reverse order it improves your technique.

During those six years we had only three surgeries on all three levels with 600-plus kids participating. When I was there, Don Chu took care of the sports medicine needs. He said one of the reasons was the kids were always in a good athletic position. Training is the sum of many things, not one individual method or exercise. We did not do any single leg strength exercises, but we did do single leg hops and alternate bounding.

This was before the core epidemic. All the things we did above train the core. Core exercises were developed from physical therapy for people who had back pain. The same physical therapist also treated the joints, the soft tissue, and the nerves. They also developed specific tests to determine which core exercises the patient needed. Did the patient need high load, low load, or the intrinsic muscles? If you don’t have these evaluation skills, then your core program is of little use.

The “Turkish Get Up” isn’t going to cure everybody’s core. I never knew making someone strong lying on their back and getting up had anything to do with playing sports. Usually, when you’re on your back in sports, it means you got your ass beat. As my good friend, the late Charlie Francis, said, just because an exercise exists doesn’t mean you have to do it. I’ve said, just because an exercise is hard doesn’t mean it’s any good.”

Just because an exercise is hard doesn’t mean it’s any good, says Al Vermeil. @SimpliFaster #coaching Share on XI saw Al Vermeil present a long time ago, but felt that contacting him would be selfish of me because retired coaches deserve time away from work, especially from all the young coaches seeking answers. He continues to speak today and was recently at the 2019 NSCA national conference. His attention to detail and no-nonsense attitude are certainly missed these days, when it seems the over-reliance on areas outside of coaching is the cause of sports performance just running in place. Talking to Coach Vermeil was a gift, and I am forever grateful for his time and efforts.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]