Introduction

From the first day I began using the Perch velocity-based training (VBT) system, I realized the most important concept of VBT: INTENT MATTERS. Intent is the key—when every repetition matters, athletes will train with more intensity, which will lead to better results in less time.

Over the past year, VBT has become a game changer for the Montverde Academy Strength and Conditioning Program. My learning curve has been steep, and I have been experimenting with many different training methods to determine what works best for our athletes. VBT has driven me to adjust my training philosophy to create better programs for the teams we serve, allowing us to measure, monitor, and manage the exercises and training loads of our athletes.

With many high school athletes playing year-round, load management and the need to adjust training for specific outcomes have become crucial in reducing injuries and improving performance. Since we began using VBT daily, I have gone back to reading some of the classic strength training books from the 1980’s to 2000, such as Supertraining, Westside barbell books, as well as more recent books like The System, and Triphasic I & II. Having read these books before where velocity was more of a concept, I am applying velocity zones which have enabled me to experiment and use the data for more effective programming.

Strength training has traditionally evolved around heavy, slow strength exercises at low velocities. On the other end of the spectrum are sprinting and jumping at very high velocities. We include timed sprints daily as part of our VBT system. We view flying 10’s as part of your VBT programming. They are an explosive high velocity exercise, not viewed solely as running.

We view flying 10’s as part of your VBT programming. They are an explosive high velocity exercise, not viewed solely as running, says @tc2coaching Share on X

Figure 1. This Chart Displays Which Velocity Zone Corresponds with Each Training Stimulus

This article will explore why it’s important to fill the gap by implementing “strength speed” and “speed strength” and how they can be applied within your training to create more durable and explosive athletes. We need to train fast to play fast.

VBT Basics

Before VBT, we educated our athletes on the value of training with intent on all concentric movements. I’m not sure how well that worked, but I do know that as soon as we installed Perch, we immediately realized that intent matters. So much so that we printed the phrase on staff shirts to ensure constant, daily messaging daily. Maximal intent is the key to maximizing any VBT system and accumulating valuable data.

Image 1. “Intent Matters” Graphic Tee Shirt

If using VBT does nothing more than get athletes to push themselves every rep—making every set count—that alone is worth the investment. By maximizing intensity and minimizing junk reps, we improve time and energy efficiency. Having visual feedback for every rep has allowed for better coaching and education for our athletes.

If using VBT does nothing more than get athletes to push themselves every rep—making every set count—that alone is worth the investment, says @tc2coaching Share on XHigh Velocity Basics

Like most programs, we will do Olympic lift variations, sprint, jump and throw in every workout. Our goal now is to train for peak velocity before adding more weight to the bar. This has improved power and explosiveness. I am now more in favor of sets of 3 reps instead of 5 or more, since we generally see velocity drop significantly after 3 reps.

For sprinting, we use timing gates and measure flying 10’s. This allows us to do 2-3 sprints every workout. I have found frequency and consistency in sprinting gives us the biggest bang for our buck, and we can easily incorporate it into our strength program.

Additionally, we have a large block wall for med ball throwing. Almost every session, the athletes execute throws with maximal intent using 4 to 8 lb. med balls.

The key to translating strength and power to athletic movements is filling the gaps between absolute strength and max velocity movements. This is where strength speed and speed strength become important. The ability to measure and adjust loads within these zones allows athletes to become not only explosive, but more durable and resilient to injury.

Strength Speed

Strength speed is often defined as the ability to move a heavy weight fast. In VBT terms, this translates into a speed of .75 m/s – 1.0 m/s. In his Westside Book of Methods, strength legend Louie Simmons states that strength speed exercises should be done with 65% band tension and 35% bar weight.

Determining band tension can often be difficult. We calculate this by using a luggage scale and stretching the band to the highest point within the range of motion. For example, our dead lift bands on the trap bar at waist level are approximately 35 pounds per band, totaling 70 pounds. If the athlete has 135 on the trap bar, then the top of the range of motion will be at 205 pounds. We have found banded trap bar deadlifts create better form for the athlete, resulting in less back stress. This allows for more time accelerating and less deceleration, thus potentially creating more glute activation.

[vimeo 1106223273 w=”800″]

Video 1. Trap Bar Speed Pull performed with Bands

Speed Strength

Conversely, speed strength is often defined as the ability to move a lighter weight fast. Force-velocity charts frequently define this as moving at a speed of 1.0 m/s – 1.3 m/s with 35% band tension and 65% weight on the bar.

I used to think that by just decreasing weight, the athlete would automatically move at a higher velocity. I have found this is a learned skill that will take time to develop and will improve power and force production. Athletes need to learn how to move fast in the eccentric phase, put on the breaks and produce a fast and powerful concentric movement. This is not natural for many athletes but is critical for learning how to transfer power to athletic movements. I have found it takes about 2-3 weeks for athletes to learn to move at 1.0 m/s or faster on lower body exercises. Be patient and move the velocity up gradually over a two-week period.

One method we have used successfully is a 4-week buildup:

- Week 1= .9-.93 m/s

- Week 2= .93- .97 m/s

- Week 3= .97-1.0 m/s

- Week 4= 1.0-1.2 m/s

The ability to decelerate, stabilize, and produce force in the concentric phase is critical to translate the strength gained in the weight room onto the athletic field or court. Putting on the brakes at the bottom of the range of motion—before reversing direction—is critical for change of direction. Kinetic energy will be stored for approximately two seconds, allowing for a fast controlled stop. Using band tension allows for a powerful concentric phase to counteract the deceleration from the high-speed movement.

After coaching hundreds of athletes doing hand-supported safety-bar split squats, I’ve observed that speed strength velocity does not come naturally to many athletes. Taking the time to develop this, however, is invaluable as it may be a key component to reducing ACL injuries by developing the neuromuscular control to put on the brakes, stabilize, and move powerfully in the opposite direction.

Filling the Speed Gap

Strength speed and speed strength reside in a gap in the velocity continuum. Most of the training year should be spent in the following velocity zones:

- Accelerative Strength- .5-.75 m/s

- Strength Speed .75-1.0 m/s

- Speed Strength 1.0-1.3 m/s

I’ve been going back and researching a lot of the old strength and conditioning textbooks where velocity was more of a concept than an objective measure, since we did not then have efficient methods to measure in real time. I can take this information and put it into velocity-based zones where I can measure, monitor, and manage the training and data (a suggested reading list is included at the end of the article).

Implementing High-Speed Training

Time and efficiency are paramount in our strength and conditioning program. At Montverde, we oversee close to 30 teams, with most teams ranging from 18-24 athletes . This is a combination of varsity and academy programs, which include several national and state championship contenders every year. By measuring, monitoring and managing through Perch, we can maximize training time and productivity without wasting valuable time and energy. Our

If You Measure It, You Manage It

Instant feedback, both visual and auditory as well as seamless data collection, allows us to seamlessly train and manage our athletes.

Measure

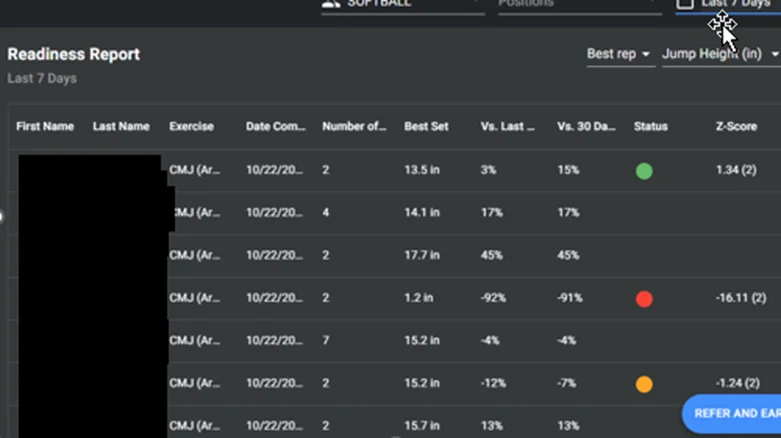

The ability to measure velocity and adjust in real time is critical to making sure we create an optimal environment and training load every day. This begins with 2 counter movement jumps to assess readiness, which is done by comparing jump height over the previous 30 days.

The Perch VBT system gives us a color-coded indicator relating to the athletes’ training status/readiness. This system, along with observing body language and energy levels, allows us to make adjustments to the team or groups of athletes based upon fatigue levels.

Image 2. Readiness report with color-coded indicators from Perch

Programming specific velocity zones for key exercises makes it simple for the coach to scan the iPads after the first set and then advise the athletes to adjust the loads to situate them into the specified velocity zone for that day. This process only works if the athletes are working at maximal intent on every repetition. A team sport athlete’s 1RM can fluctuate as much as +/- 15% on a given day, which can be caused by a range of factors including competition, travel, late night studying, tests, lack of sleep, hot weather, etc. The ability to adjust loads using velocity allows for individual adjustments and can help prevent under- or over-training.

In the weight room, boys tend to overestimate their strength and power, wanting to push more weight than they can handle. Maintaining proper loads and velocities is the objective will help reduce injuries and maximize the training effect. The velocity zones dictate the weight used. On the other hand, female athletes often gravitate to lighter weights. Having them increase weight as velocity improves has led to large gains in strength and power. Girls need to be educated that strength and size are not the same. Being strong and powerful reduces serious injuries and boosts confidence and self-esteem.

Monitor

Within the training session, the coach can monitor each rack and coach the athletes. Since using VBT, we have been moving towards more sets with lower reps per set. This gives us more quality repetitions in the zones that we desire.

Moving to 4-6 sets of 3, with shorter rest, ensures we are training the targeted capacity. This is especially true when working in the strength speed/ speed strength zones. Since we are not grinding out reps or going to failure, this leaves the athlete less fatigued in their team sport practices or games.

Manage

The software side of VBT is where the magic happens. An all-in-one system such as Perch allows us to plan, evaluate, and train all in the same system. The ability to easily access force velocity curves, estimated 1RM, and power outputs produces an efficient system that collects data in the background while you train.

Using “percent drop off” is an effective way to manage training load in season, allowing us to adjust to training load and control fatigue during the season. An example would be programming a trap bar dead lift for 5 sets of 4 reps with a 3% drop off based on best rep. If the velocity drops more than 3%, the set is terminated.

This means that some athletes may get 4 reps per set while others 3 or 2, which keeps the velocity constant and the reps variable. Athletes who play a lot of minutes and accumulate fatigue will do a little less volume, and those who are not playing as many minutes may do more. This keeps the highly motivated and driven athletes from doing too much but ensures quality on every set. Percent drop off works well the day before or the day after competition.

Programming Case Study with Girls Soccer

To illustrate how we target strength speed and speed strength within the context of an actual training year, we will look closer at our girls’ soccer program.

The team arrives on campus in the middle of August and will begin preparing to play their fall club schedule. Most of the athletes will be coming off of a summer break of several weeks to 2 months of no games and practices. Some new athletes may have a very low training age, and others will be coming off a summer break. This summer we are using the Perch Mobile app to send summer strength workouts. This will consist of two- 3 week blocks to build base strength before arriving on campus. We hope this will help in the fall season and reduce early season injuries. The first 3–4-week block will be spent slowly increasing volume and weight. We teach the athletes the basics of VBT and how to log in and access programs.

Next, a 3-week block will begin using VBT for 3-4 key exercises per workout. These will be in the accelerative zone (.5-.75 m/s). Some explosive exercises will also be introduced, such as hang cleans, push presses, or med ball throws .

Games are played on the weekend during this time of the year, so consistent weight room sessions are not interrupted. The program has just begun using GPS data, so this fall we will have game data to help us better understand the player load management. In the past we relied on coach feedback on fatigue levels. The team comes into the weight room during the last period of the school day, before heading out to the field for training. A typical week would look like the following:

- Monday—Upper body strength/run drills/flying tens

- Tuesday—Lower body/core emphasis

- Thursday—Full body workout

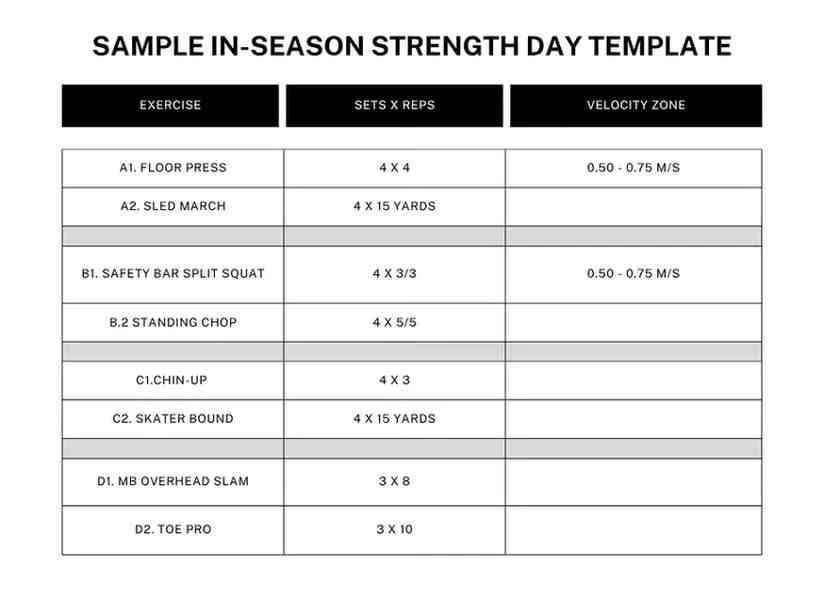

In mid-October—three-to-four weeks before the high school season begins in early November—we will switch to a strength/ speed model. Monday and Tuesday will be strength emphasis and Thursday is strength speed emphasis.

Once the high school season begins, the team often plays two or three games per week. Games will inevitably fall on planned weight room days, so our goal is to get three strength workouts in during a two-week period throughout the season. GD -2 (game day minus 2) we will do a strength workout. GD -1 or the day after competition, we will target a speed emphasis. For November and December, speed days will be strength speed (.75-.1.0m/s) for key exercises, and January/February will be speed strength (1.0-1.3 m/s) for key exercises.

When the high school season ends, the players will shift back into club mode until late spring. Since they have been training consistently since August, we try to mix it up by implementing a modified block system. Each block is two weeks and will alternate between accelerative strength/ speed strength/ strength speed. This plan allows for a good amount of variety and enables us to keep working on our strength and power levels until the end of the school year.

WANT FOUR MORE TEMPLATES FOR AN IN-SEASON DYNAMIC DAY, ACCELERATED STRENGTH BLOCK, SPEED STRENGTH BLOCK, AND SPEED STRENGTH BLOCK? THERE’S A FREE PDF AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS ARTICLE

Next Steps

Although we have been adhering to established velocity zones, I believe there is room for variation depending upon the specific exercises and sports demands. We have seen exceptional results in reducing injuries and translating the work we’re doing in the weight room onto the athletic field and courts—we are just scratching the surface on how to maximize velocity-based training into our programming.

Most of the VBT research has been conducted with Olympic Weightlifting. Do these zones apply to other exercises, or do the zones need to be adjusted? Time and practice will tell. As more strength coaches and schools embrace VBT, the shared knowledge will help our athletes become more durable and powerful.

Through research and daily, hands-on training with hundreds of athletes, we have learned a tremendous amount by fully embracing velocity-based training. The days of only sets and reps are over—it’s time to fully embrace VBT.

Suggested Reading

Triphasic II, Cal Dietz

Developing Explosive Athletes, Bryan Mann

Supertraining, Siff and Verkoshansky

Book of Methods, Louie Simmons

Conjugate Method, Louie Simmons

Velocity-Based Training, Nunzio Signore and Randy Sullivan