Because nothing in life is perfect, daily stressors inevitably will inhibit our ability to train optimally. I knew I couldn’t manage the external stressors that my athletes experienced, but I decided I could create something that would account for their level of readiness on any given day.

The Stress Scale for Athletes dramatically changed the way I train athletes. The scale allows me to apply the appropriate training load for a session based on an athlete’s readiness that day despite any stresses they’re dealing with outside the gym. I’ve used it for the past eight months, and it has served us surprisingly well with significant results.

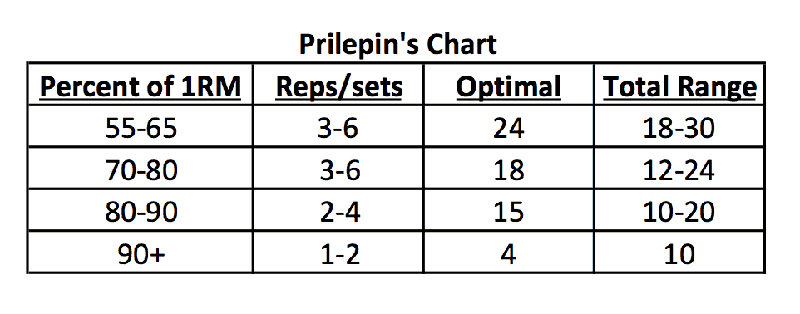

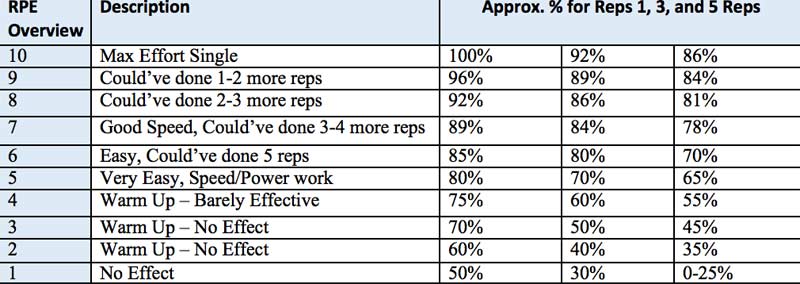

The information I present is a culmination of existing concepts, including the Prilepin’s Chart, the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) scale, and fatigue management concepts I’ve put together based on “in the trenches” empirical data. I’ve recorded hundreds, if not thousands, of different numbers in my ten notebooks that I carry with me daily. I hope this information helps you well in your training and coaching.

Recognizing the Stress Problem

We all experience stress. Stress manifests itself in many ways, both acutely and chronically. Furthermore, all stressors are not created equal—to an extent. However, both types of stress have a large effect on our training and the ability to recover from each training session.

A training session consisting of 4×10 volume squats puts significant stress on the body and will cause fatigue in most of us. Emotional pain is a stressor as well, for example a break up with a significant other. One physical, one physiological, both cause systemic stress on the body that will inhibit optimal subsequent training sessions.

When thinking about stress, it’s useful to start with the General Adaptation Syndrome. Very small amounts of stress won’t provoke a very robust adaptive response, while more stress increases adaptation. Too much stress—to the point where we can’t cope physically or psychologically— decreases the rate of adaptation.

Keep in mind that, while our bodies don’t differentiate types of stress to a great degree, the specific adaptations to various stressors (lifting weights, a car crash, and tight work deadlines, for example) will differ. Also, the body’s general response to any stressor is very similar regardless of the specific stressor we encounter.

This means that all the stressors in life pool together and dip into the same reservoir of “adaptive reserves” available for recovering from those stressors. This allows us to adapt so we’ll be better equipped to handle them next time. With strength training, this means bigger and stronger muscles, more resilient tendons and connective tissue, and bones that can handle heavier loading.

Our bodies need a certain amount of stress to function normally. If we remove all the stressors from our lives, our bodies begin to deteriorate. For example, if we were to win the lottery and spend a year lying on the couch watching reality TV, facing no stressors that challenge us physically or mentally, we’d be much weaker and in much worse health than we are now with some baseline level of physical and psychological stress.

When stress levels exceed our adaptive reserve threshold, additional stress has negative effects. Share on XPast that baseline level, additional stress causes beneficial adaptation with diminishing returns and eventually negative returns. The first input of any stress causes the largest beneficial adaptation. More stress will have an additive effect, though each additional unit of stress doesn’t add as much benefit as the first. Once the total amount of physical and psychological stress exceeds the threshold of what our adaptive reserves can handle, any additional stress will cause negative effects.

My Challenge as a Coach

It’s nearly impossible to monitor an athlete’s stress levels since we have little control over the external things that happen to them outside the weight room. In most cases, we see our athletes no more than 8-10 hours a week. There are 168 hours in the week. That leaves athletes with at least 158 hours experiencing other external and internal stressors.

As coaches, our job is to ensure our athletes feel good, are ready to perform, and can sustain a healthy lifestyle that is conducive to sport success. Because we cannot control everything that happens outside the gym, we must create training programs that will most benefit our athletes no matter what’s going on in their lives.

Coaches must create training programs that most benefit athletes despite their life stresses. Share on XMy professional athletes are always ready to go because they’ve dedicated their entire lives to training. They take the necessary steps to put themselves in the best position to succeed. I don’t train many professional athletes at a time, however, because of their busy schedules.

Like most coaches, the bulk of my athletes consist of high school and collegiate athletes, ranging from 14-22 years old. Thisis where things get tricky. We all know what amazing things happen during those years: partying, late nights, relationships, breakups, school work, and the daily stress of home life. These may seem small to us now, but we all remember how much they influenced us at that age and how we felt on a daily basis.

One week my athletes came in, and the weights were moving. They were hitting numbers 25-30lbs over what we prescribed for the day. The problem with this happened during the following weeks of training. They did not even come close to the numbers they were supposed to hit based on their performances the previous week. As always, I asked them how they felt, what they ate, how they slept, and how their weekends were. The answers always changed. “I didn’t sleep well” or “I had a rough weekend” or “I didn’t have time to eat.”

This was when I knew I couldn’t keep prescribing the same thing week after week with minor tweaks here and there. I needed a holistic training program overhaul.

Concrete Steps Toward a Solution: Stress Scale for Athletes

Since I couldn’t manage the external stressors my athletes experienced, I created a method to account for their level of readiness on any given day. Below are outlines of two tables you may have seen before.

As the reps increase, the perceived intensity of each load decreases. Obviously a 5RM should be at a lower percentage than a 1-2RM, which is why 5 reps @ RPE 5 would be about 60-65% and a single rep @ RPE 5 would be around 80%. Volume work around 80% of your 1RM could fall anywhere between 3-6 reps, so an 80% single would be no problem, thus an RPE 5 on the RPE Scale.

At this point, I had Prilepin’s Chart and an RPE table with estimated percentages that closely resembled Prilepin’s Chart. I now needed to account for how the athletes felt, how much volume they could handle, and how much they could recover from each training session.

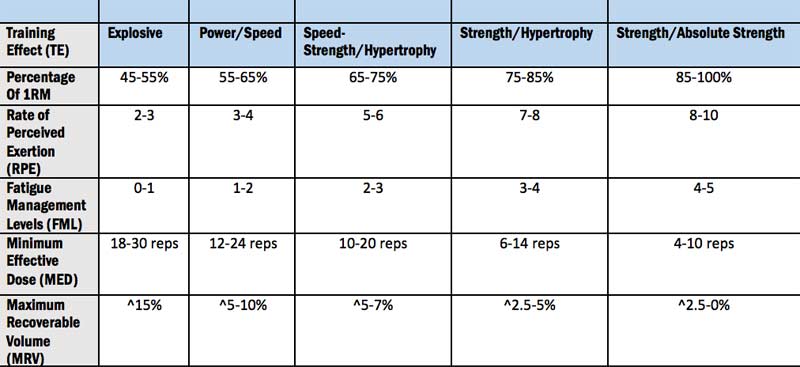

When looking at the Stress Scale for Athletes, keep in mind these key definitions:

- Training Effect (TE)—the training objective and desired effect for the day.

- Percentage of 1RM—based on Prilepin’s Chart, the objective of each percentage.

- RPE—a number value based on effort and associated with a given percentage of your 1RM.

- Fatigue Management Levels (FML)—how fatigued you are, based on your RPE.

- Minimum Effective Dose (MED)—the minimum amount of volume to get the desired outcome and training effect for that training session, based on Prilepin’s Chart.

- Maximum Recoverable Volume (MRV)—the most amount of volume an athlete can handle during a particular training session to recover and progress in the subsequent training session. This concept was brought to me by Dr. Mike Israetel of Renaissance Periodization and has been extremely useful in training my athletes.

How to Start with Your Athletes

Here’s how to use the Stress Scale with your athletes. Start by asking them how each set felt, starting with warm-ups up to their working sets. Use the chart to compare and contrast your data. From here, you can modify the training plan based on how your athletes feel that day. I left room for flexibility because everyone is going to perceive certain training loads differently. This allows more flexibility in your coaching program as well.

Based on all of the information in the table, here is an example of how I would use the Stress Scale with my athletes.

Example of the Stress Scale for Athletes

1RM Squat = 315

Work for the Day = Squat 3×5 @ RPE 7 | 70-75% = 240

- Bar x 10

- 135 x 10 @ RPE 4 | 50% x 10

- 185 x 5-8 @ RPE 5 | 60% x 8

- 225 x 5 @ RPE 7.5-8 | 70% x 5

- 240 is the target range for the day but 70% (225) felt like an 8 RPE according to the Stress Scale; 70% should be an RPE 6-7 at the most. This would put your fatigue level at 3 vs. 1-2 according to the Stress Scale.

You now have two options:

1. Option A. Cut back to 225 @ RPE 7 (70%) and hit your MED—15 reps.

2. Option B. Go up to 240 @ RPE 8 but cut back your volume to 6-14 reps total (MED for that range).

- FML represents how fatigued the athlete is for that particular day or possibly week. It’s not perfect, but it is a very strong representation of the athlete’s output for that training session. Overall intensity does not always create the most stress. Overall volume can cause significant stress for an athlete as well.

Observations and Results

I’ve been using the Stress Scale for eight months. During this time, my athletes have hit numerous PRs. More importantly, they’re always working within the appropriate ranges for the day as opposed to trying to hit percentages or numbers based on what they did last week. They’ve progressed week to week without overexerting themselves, which protects against getting hurt.

The Stress Scale also allows the athletes to take ownership of their bodies and how they feel. Our job as coaches is not only to lay out a plan and guide our athletes, but to teach them how to take care of their bodies, how to train properly, and how to live a healthy lifestyle. The Stress Scale helps give ownership and accountability to my athletes.

Final Thoughts

Training athletes is about health, progression, and longevity. There is a time and place for heavy metal, ammonia caps, and yelling. However, the day in and day out grind will not always provide these energy levels. We need a way to improve our athletes every single time they step foot in the facility. I hope this becomes a useful tool that you can use in training yourself and your athletes.