Matt DeLancey is entering his 16th season working with the Florida Gators and is currently their Assistant Director of Strength and Conditioning. While collaborating with excellent sport coaches, he has had the opportunity to work with 110 Olympians and 25 medalists over the past four Olympic cycles and 130+ NCAA individual champions in swimming & diving and track & field. He has also assisted in winning eight NCAA and 27 SEC team championships. “Florida has excellent athletes, savvy coaches with elite knowledge, and a relentless support staff that all collaborate in an effort to produce elite performances.”

Matt completed his undergraduate degree in Physical Education and Health at East Stroudsburg University in 1998. He taught and coached briefly at Carson Long Military Institute before coaching and playing for the Styrian Longhorns in Graz, Austria, as part of the EFAF. When he returned to the States, Matt completed 24 master’s credits at Northern Illinois University. He took an internship at the University of Richmond over the summer of 2002 before landing at the University of Florida in August 2002 in the same role. In May 2003, the Gators promoted him to assistant and then assistant director in February 2005. Matt currently holds CSCS, USAW, CES, and PES certifications/specializations.

Freelap USA: You use the snatch for a very challenging population: swimmers. Can you share why you use this exercise and why you have such success with it? I think after a decade of recordkeeping you must have some great viewpoints.

Matt DeLancey: Snatch transfer series and snatching is as much an ongoing assessment as it is a training modality for us. We find initial dysfunction in the overhead squat and address it. As it starts to look better, we move to the pressing snatch balance and the snatch balance and continue the same process. The faster and more complicated the movement is, the more dysfunction we find and continue to address. By the time we have them snatching, we’ve grooved a nice snatch pattern and have addressed critical dysfunction.

We use the Snatch transfer series as part of our warmup two out of three times per week. We are also a very healthy, high-performing NCAA swim team with several elite international performances. Results are part of the evidence that shows if what you are doing is right for the given athlete.

Freelap USA: With jumpers, what do you do differently—if anything—than for sprinters? Maybe a better question is whether there is a difference in your programming?

Matt DeLancey: Our jumpers are typically stronger in the squat variations, cleans, and snatches than our sprinters. We have a larger emphasis on eccentric and isometric loading with them throughout the fall than we do with our sprinters. We utilize a variety of box heights and squat depths for our jumpers and will add eccentric and isometric components to those movements. Jumpers have to be strong and confident about their strength.

We also rest as hard as we work when it’s time to rest. If I see any of our athletes come into the weight room and they look depleted, I will modify the workout or even cut it. I think people sometimes get too stuck on “the plan” instead of doing what a particular situation needs.

People sometimes get too stuck on ‘the plan’ instead of doing what a particular situation needs. Share on XFreelap USA: Athletes are training harder now, and we are seeing cases of rhabdomyolysis again at the lower levels. With many athletes doing doubles and triples, some are coming to college with histories of possible rhabdomyolysis. How can coaches tease out training histories and medical records to help see if an athlete might have had a problem?

Matt DeLancey: I talk to our athletes daily. Asking questions like, “How do you feel today?” are valuable assessments to their general well-being. If you ask questions and truly listen to their responses you will gain a solid understanding of that athlete’s Perceived Exertion Scale and their well-being scale. Deviations in their responses are situations that need immediate evaluation. Also, notice if their scale matches up to what is really going on.

I was working with an NFL rookie this past week who had an AC joint sprain and we’ve been progressing back into some overhead pressing. We had an unloaded barbell and he said he felt discomfort. I asked him to rate it on a scale of 1-10 and he told me a 4. I asked him if we needed to modify and he said yes. I explained to him that we modify at 5-6, so he was probably a 6 instead of a 4. We changed to a neutral grip bar and he said it felt better and that he could work with it. I then explained that was a 4.

This simple communication will help him understand the difference when he needs to modify. If he keeps living at a 6 but treating it like a 4, that probably would take a few years off his career. This concept is one of the most important things we should know how to do as coaches. “Do no harm” should be our mantra.

Freelap USA: You have worked with other coaches who are coming up the ranks and need experience working under coaches who can teach properly. Besides visiting, training, and coaching more, what are ways you learned to instruct better?

Matt DeLancey: My undergraduate degree was in Physical Education and Health from East Stroudsburg University. I learned how to write and implement lesson plans there. I feel we should encourage our young, aspiring coaches to go into a PE and Health program that has a strong science background as well. We were also required to take exercise physiology, human anatomy and physiology 1 and 2, kinesiology, care and prevention, order and administration, and a wide variety of activity classes equaling 13 total classes.

Those activity classes required at least one aquatics; one gymnastics; one dance; special populations; beginner, intermediate, and advanced movement; and team and individual sport electives. We had a non-traditional physical education class where we learned to modify and adapt activities for every skill level to be successful. I lean heavily on what I learned at ESU.

Freelap USA: New information is important, but classic principles are vital now more than ever. Could you share some textbooks—perhaps three—that are older and less known for coaches to learn from?

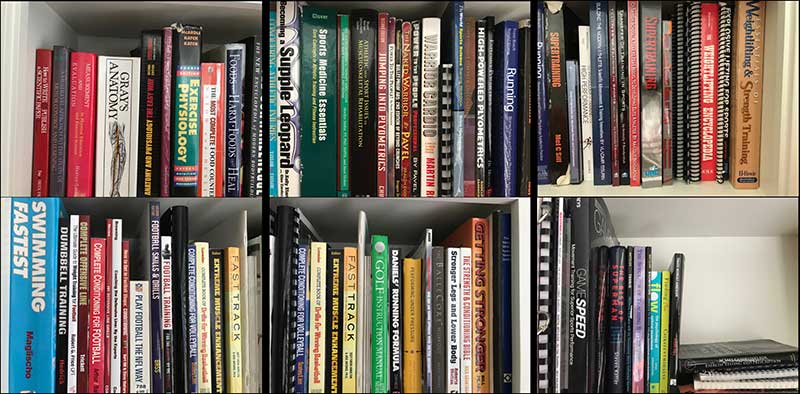

Matt DeLancey: Here are just some of the books I have. The list is long, but take a look at the sample shown on the photo series.

Editor’s Note: “Swimming Fastest” by Maglischo, “Supertraining” by Siff, “High-Powered Plyometrics” by Radcliffe, and “Transfer of Training in Sports” by Bondarchuk are all excellent reads.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF