[mashshare]

Graeme Morris is the Head Strength and Conditioning Coach of the Western Suburbs Magpies Rugby League club. He designs, implements, and monitors all aspects of physical performance, including strength and power in the gym and speed, agility, and conditioning on the field. Prior to this role, he was at the Newtown Jets Rugby League Club for five seasons. Morris holds a degree in human movement with honors in exercise physiology and a master’s in strength and conditioning.

Freelap USA: What is your approach to training agility and change of direction in light of ideas on perception-reaction, “game speed,” and multidirectional speed?

Graeme Morris: First and foremost, I think it’s important to differentiate between agility and change of direction. As I’m sure most readers are aware, change of direction is a closed, pre-planned skill without the perceptual-cognitive processes.1 Agility is an open skill, such as a whole-body movement with a change of direction, rapid acceleration, or deceleration in response to a stimulus. Agility involves perceptual and decision-making methods such as visual scanning, knowledge of the situation, anticipation, and pattern recognition.1

While perception-reaction and finding movement solutions are currently all the rage, I still think closed drills such as change of direction have value, says @GraemeMorris83. Share on XWhile perception-reaction and finding movement solutions are currently all the rage, I still think closed drills such as change of direction have value. If the athlete’s only tool is a hammer, then they will treat everything as a nail. It’s hard for an athlete to come up with a movement solution if they don’t have mastery of fundamental movement patterns such as deceleration, shuffle, open cut step, crossover step, etc.

I like to initially develop these patterns in a closed setting at slow speeds so that athletes can perfect technique and engrain good motor habits. These movements can then become more reactive, more specific, placed under cognitive stress, and then placed into sporting context. Athletes sit on a continuum of unconscious incompetent all the way to unconscious competent. As coaches, we need to layer these drills so that our athletes develop mastery and become unconscious competent performers in a sporting environment that requires perception, reaction, and decision-making.

Here are four phases I have adopted from Keir Wenham-Flatt that coaches can utilize throughout the pre-season period.

Phase 1

Closed Environment – Micro-dose deceleration, shuffle step, cut step drills, crossover step drills at the end of the warm-up.

Video 1 (here). Use multidirectional tempo training one day a week to build aerobic capacity and master different movements.

Phase 2

Make drills more reactive – e.g., the shuffle drill now becomes a mirror drill, and on the whistle, the shadow needs to catch the other athlete.

Phase 3

Make drills more open and allow athletes to play. These drills should be more chaotic in nature.

Video 2 (here). In Phase 3, agility drills should become more chaotic in nature.

Phase 4

Add in game-like scenarios that involve agility, small sided games, and actual team practice. Please note: The head coach usually has the best drills, as these are highly specific.

In-season we may spend 15 minutes a week on these concepts with drills that expand on the warm-up. For example:

- 5 minutes general warm-up

- 5 minutes closed drills

- 5 minutes reactive/open chaotic drills

Freelap USA: What are some of the primary tenets of linear speed development you utilize with your training population?

Graeme Morris: Linear speed development is an important part of my program. Whereas agility and change of direction occur in every single training session and game, athletes quite often don’t achieve maximum velocity (<90%). However, when maximum velocity does occur, it is usually in a game situation that is critical. I think training maximum linear speed is very important for many reasons, including:

- It increases max velocity, including an improved acceleration profile.

- It increases speed reserve. If we develop and improve our ability to run faster, the game (operational outputs) is slowed down compared to maximal outputs. This increases our work capacity, as we now work at a relatively lower intensity than previously.

- It reduces injuries. Malone et al. showed that exposing the body to close-to-maximum velocity has a protective effect on lower limb injuries.2 Furthermore, the more efficient an athlete is at running, the less chance of non-contact injuries.

- It improves momentum. Momentum is a product of mass x velocity. For collision sports such as Rugby League, first contact is crucial.

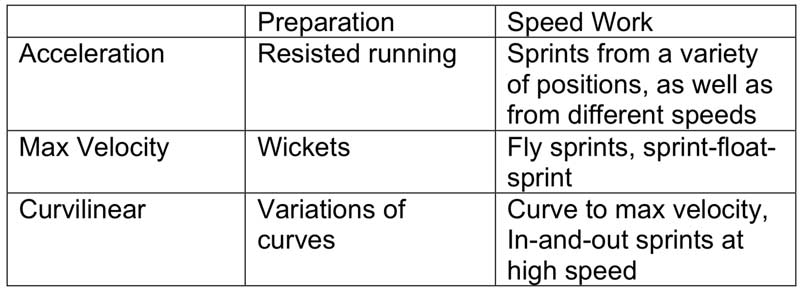

Typically, in the preseason I like to go from short to long. I think this is more appropriate for team sport athletes, as it allows you to progressively load the athlete with more sprint meters over time. The three main phases of focus are acceleration, max velocity, and curvilinear. I’m a big fan of using resisted work for acceleration, wickets for max velocity, and different curve variations for curvilinear. These drills allow my athletes to work on projection and hit nice postures that relate to each ability. Once my athletes have a base of this, I may include some perception-reaction under max velocity conditions. Special mention to Matt Jay from the Cronulla Sharks, who inspired some of my curvilinear drills.

I begin every session with speed power drills such as Mach and some Chris Korfist and Frans Bosch drills to help with rhythm, coordination, and timing, as well as develop some stiffness of the lower limbs. In contact sports such as rugby (both codes), coaches always emphasize force, toughness, aggressiveness, and contact. Typically, rugby athletes struggle initially with the ability to relax and to get the correct timing and sequencing. With many of these drills, I like to progress them by including the switching of limbs such as booms, and boom booms to train this ability. Jonas Dodoo wrote a wonderful article on how he considered limb exchange as one of the limiting factors for sprinting.

I’m a big fan of tempo training, so that athletes can concentrate on frontside mechanics and arm positioning when running at slower speeds, says @GraemeMorris83. Share on X

I’m also a big fan of tempo training, so that athletes can concentrate on frontside mechanics and arm positioning when running at slower speeds. As mentioned earlier, I really like the use of resisted runs and wickets. These environmental constraints help force athletes to self-organize and find positions that are more efficient. I find this valuable when dealing with many athletes at once. Providing a simple cue each rep allows the coach to try and get rid of common running problems seen in team sport athletes.

Freelap Friday Five: How do you utilize the “robust training” ideals for your rugby athletes?

Graeme Morris: There are two aspects that I think of when discussing “robust training.” First, are my athletes able to withstand the high loads of running and contact needed throughout a long pre-season and competition period? If athletes are not robust and haven’t developed high amounts of resiliency, you will lose many players throughout the season. It’s important to have principles in place so that you can systematically load players without large training spikes, enabling them to adapt to the stressors placed upon them. The principles I adhere to are:

- Simple to complex

- General to specific

- Extensive to intensive

- Low intensity to high intensity

- Closed to open

- Technique before load

- Slow to fast

It’s also important to develop resiliency around areas that are prone to injury. Common soft tissue sites are hamstrings, adductors, calves, and quads. Rugby League is a collision sport and, thus, players need to develop armor around the core, shoulders, upper back, and neck.

Robust running is a popular term being discussed currently. This is the ability to maintain rhythm and timing when running under the pressure of different tasks and environments such as avoiding a defensive player. Speed power drills and sprint drills can become more complex by crossing the arms across the body or by using a pole placed across the shoulders or above the head.

The addition of aqua bags seems to be the latest trend. However, to me this is not a starting point. Like all exercise progressions, make sure the athletes have mastered the basics before increasing difficulty. You must crawl before you walk, walk before you run, and run before you sprint.

Freelap Friday Five: How do you approach specificity of strength for the needs of rugby?

Graeme Morris: It’s important to realize that strength training exercises are general in nature. However, all exercises sit on a continuum from general to specific compared to the competition exercise. In Rugby League, the main movements are running, change of direction, and grappling. It is important to develop the adaptations that will improve these qualities.

From the weight room, there are several goals I try to tick off for my athletes. These are:

- Develop a high amount of general strength and power in general exercises such as the squat, hinge, push, pull, rotate, and the frontal plane.

- Develop resiliency around areas that are prone to injury. I discuss common injury sites above.

- Develop speed and power in the force producers of movement. If we look at sprinting, the hip extensors such as proximal hamstrings, glutes, adductor magnus, and psoas all need high-velocity strength.

- Strengthen the force absorbers of the movement: The hamstrings, quads, and calves are all important force absorbers in sprinting and change of direction. Isometric and eccentric progressions for these muscles allow the athlete to better absorb force.

- Use appropriate jump/plyometric progressions to optimize power production and absorption.

I believe a sprint, agility, grappling/wrestling program combined with jump/plyometrics and strength training principles covers the many bases of a Rugby League athlete. I don’t have my players running up stairs with aqua bags, as I’m wary they get a lot of specificity on the field. An exercise does not need to necessarily look specific if the adaptations it produces will be positive for the athlete’s needs.

An exercise does not need to necessarily look specific if the adaptations it produces will be positive for the athlete’s needs, says @GraemeMorris83. Share on XMax strength, explosive strength, elastic strength, and strength endurance can all be integrated using a vertical integration scheme pre-season and a conjugate scheme in-season. As athletes increase their training age, more specificity can be added in the gym. It’s important that my players don’t break in collisions or under the high loads of a long season.

Freelap Friday Five: What are the “big rocks” of hamstring injury prevention in your system?

Graeme Morris: The hamstring injury is one of the most common soft tissue injuries in team sport athletes. It’s imperative to come up with prevention methods to try and reduce the likelihood of injury. I believe it’s important to have a holistic approach, as injuries are multifactorial in nature. The main areas I tend to focus on are:

- Load Management – Use intelligent programming. I have already mentioned the principles I adhere to. The most important thing regarding load management is to try and minimize large spikes in training loads, such as sprint meters, very high intensity running, volume, accelerations, and decelerations.

- Hamstring Strength – Recently, there has been the argument of whether the hamstrings act eccentrically or isometrically at terminal swing of sprinting. Either way, training both contraction types will elicit positive adaptations to the hamstrings. In the pre-season, utilize isometrics early in the week (less DOMS) and the eccentrics later in the week, so that the athlete can recover over the weekend. Using technology such as the NordBord allows the measurement of hamstring strength so if there are any deficiencies, they can be red-flagged. Use common sense in-season and place eccentric work within a weekly structure that won’t affect performance.

- Sprint – Malone et al. showed that exposing athletes to regular sprinting has a protective effect on lower limb injuries.2 In-season, we aim to expose every athlete to maximum velocity (>90%) at least once a week, at a minimum. Certain positions such as outside backs will need repeated exposures throughout the week to suit their positional requirements.

- Sprinting Efficiency – I think sprinting mechanics are extremely important to reduce the likelihood of hamstring injuries. As Dan Pfaff states: “There should be a technical model with common denominators of position, movement schemes, and vectors.” We need to be able to coach our athletes to move within these bandwidths to optimize performance and reduce the chance of injury. “The body loves biomechanical truths.”

- General Well-Being, Mobility, etc. – I like to screen my athletes before every field session to see if they are run-down, sore, tired, tight, etc. From there, a conversation can occur, and the athlete may see a physio or do some extra mobility/stability work, or there may be a change to the program depending on the situation.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

1. Sheppard, J. and Young, W. “Agility literature review: Classifications, training and testing.” Journal of Sport Sciences. 2006; 24(9): 919–32.

2. Malone, S., et al. “High chronic training loads and exposure to bouts of maximal velocity running reduce injury risk in elite Gaelic football.” Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2017; 20(3): 250–54.