Jake George Schuster is a sports performance coach and researcher, most recently with New Zealand Rugby, specializing in speed and power for rugby sevens. Jake hails from Boston, Massachusetts, and grew up playing lacrosse and wrestling before entering the world of strength and conditioning and sports science.

Freelap USA: Sled loads are still popular now that some new research is showing the value of going higher than the 10% body weight load. As a fan of training for velocity and maximal strength for team sports, what is a good composite suggestion in a training program? With only so many resources available, should coaches decrease loading on the lifts in favor of heavy sled work or should they profile players before designing workouts?

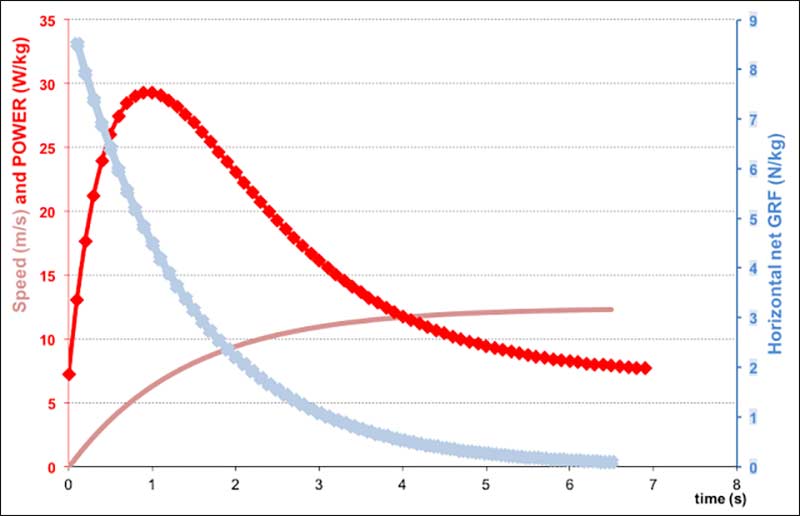

Jake Schuster: Yes, more research out of J.B. Morin and Pierre Samozino’s group, including (the outstanding) Matt Cross’ master’s thesis, has shown how valuable heavy sled training can be. I was a subject in one of the main studies there and I remember we had a sprinter who didn’t exhibit peak power output until loaded up at over 110% of his body weight! So, it’s highly individualized again, and I don’t see why sleds would be different from any resistance training in terms of overload principle.

Thanks to the recently designed app, profiling is cheap and easy, and can tell—for example—if prescribing a bound or heavy prowler march is a better use of time with athletes. At the risk of modern cliché, teaching athletes how to move properly should take precedence over any desired physical capacity stimuli deemed necessary for their sport. It doesn’t matter how strong they are if they get injured from poor movement.

Teaching athletes how to move properly should take precedence over physical capacity stimuli. Share on XFreelap USA: Testing horizontal jumps and vertical jumps is common, but what is a great way for larger football athletes to train for the horizontal qualities? With bounding being out of the equation for linemen, how can we get NFL athletes exposed to a well-rounded system?

Jake Schuster: Sure, we probably won’t see 300+ pound linemen doing beautiful sprint bounds, but I’m sure we can coax them into doing hops and other basic jumping exercises. Those guys still footstrike, albeit not often at super high velocities, but with a lot of mass and therefore force. Beyond that, inverted or prone hip extension exercises can, in my experience, not only enhance horizontal force production capabilities but also instigate the lumbo-pelvic stability required for outstanding and efficient movement.

Furthermore, prowlers are incredible tools with far more to them than meets the eye. It’s not as simple as bending the arms and grinding like a madman: Practice posture, head-to-toe length and stability. Try marching (holding positions, then slow moving, then fast) and bounding. Band-resisted marching or horizontal leaping can be effective as well. Lastly, don’t forget good old kettlebell swings and hip thrusts.

Freelap USA: The Contreras study created controversy because some people feel that squats do have the support to prove that they can transfer to short sprints, while the study showed it wasn’t adequate to make a real, positive contribution. With different populations and different strength programs, what is a good way to look at hip strength and acceleration?

Jake Schuster: To me, all this controversy and hubbub is silly, as the “answer” in my mind is obvious: There is no answer, do what works for YOUR athletes, have some sense and try different things and see what works for each group and each athlete. Some athletes love squatting, squat well, and improve from squatting. Others break down badly or simply squat themselves slow.

Bret’s research there was sound. I helped run the intervention and observed much of the data collection. It was a well-run study with true results—Bret just has a lot of haters! It’s a lot of noise for little reason—my experience is that the hip thrust is a great exercise. Let’s not start a war over exercise selection until all of our athletes are sleeping 10 hours per night and eating like Spartans.

All of the papers out of J.B. and Pierre’s research group are showing that application, rather than magnitude of force, is a difference maker in sprinting, especially acceleration. My own research (in submission for publication) is showing the same. This aligns with the growing notion that “strong enough” is probably a lot less strong than many of us would like to admit.

With that in mind, teaching proper mechanics/skillset/ability to produce horizontal force with economical movements conducive to sporting action is far more valuable than simply building hip strength. How often in sports, outside of a basketball rebounding, do we stand on two feet and squat down before raising back up? About as often as hip thrusts, true, but my point is that teaching basic jumps, bounds, simple knee drives, and what Frans Bosch calls “hip lock,” does the job at least as well as squatting does, in my experience.

Freelap USA: Fitness testing for team sports isn’t easy to do when training time limits coaches. Could you share how you evaluate someone’s conditioning in a way that is practical yet scientific? Perhaps something for a small college or high school program?

Jake Schuster: Fitness testing is a pain in the butt in that nothing we can try will ever replicate the exact (and often highly variable) sport demands. Therefore, the most important thing to keep in mind when talking fitness testing is that it’s just a number, to be taken with a big grain of salt. For me, specificity will still and always rule, and we get away from it too often.

Training rugby sevens athletes? Design and regularly administer a test that lasts about 15 minutes, ideally with a one-minute break in the middle. Luckily, a Level-20 Yo-Yo does, for all its flaws, take about this long. I’m a big fan of rowing, too. A two-kilometer row test is monstrous, but gives a good idea of conditioning. That said, however, if you’re playing your sport for 80+ minutes, is that really relevant?

A long run doesn’t make much more sense in my mind either, especially in contact sports. I’d say pick a test or two, acknowledge the (huge) limitations, and never let it become a be-all and end-all. If a basketball player who normally gets 20 on the Yo-Yo comes back from his vacation and runs a 15, you’re in trouble, but don’t freak out if he gets 18.5! Make sense?

Freelap USA: GPS data has some value, but it’s also overused and misinterpreted. Could you share, in more detail, what the line of value is with this type of technology? Simple workloads are convenient for monitoring but some limit exists. Can you show a few pitfalls that why GPS needs really smart coaches to reveal value?

Jake Schuster: For all their cost, GPS-accelerometer monitoring systems can and should be used to valuable effect with a minimalist approach in my mind. I vehemently disagree that the systems require really smart coaches. If that was the case, I’d be in big trouble when I look at them. As with anything, numbers are just numbers. Meterage (m/min) doesn’t mean someone worked crazy hard per se; it just tells you how much they did in a certain period of time.

Once we create standards and patterns, we can really save our players from ourselves by using the numbers. For example, if we know that a rugby sevens athlete runs around 250 high-speed meters during a match, and JimBob has been known to tweak a hammy in the second game of a day, next time you go to run a session and get past 250 high-speed meters, keep an eye on JimBob and pull him out of sprints if he looks wobbly.

Many teams are (smartly, I think) modeling their training weeks around match demands, i.e., trying to achieve at least 70% of the high-speed meters typically run during a match, throughout the training week. This is pretty simple to do and can help inform the coaches where they’re at week by week, how it relates to the match, and what types of loads are producing what types of responses in the athletes.

Lastly—and this is still a limitation of the technology but it’s getting there—the units can tell us what velocities the athletes are achieving. So, if you want to make sure JimBob hits within a specified kph of his max velocity twice during the week, so that inhibition mechanisms don’t pull his hammy off the femur during match day, you can just have a look at the live feed and tick that box! I don’t think we need to get overwhelmed by GPS, and most of the providers have great customer service anyway.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

What app do you mean for profiling the sled work?