[mashshare]

Dr. Brad DeWeese is an assistant professor in the Department of Exercise and Sport Science in the Claudius G. Clemmer College of Education at East Tennessee State University. He spent the past eight years preparing athletes for the Olympic Games and was the strength, speed, and conditioning coach for nine athletes and two alternates who went to Sochi. DeWeese began coaching these athletes while serving as head sport physiologist for the U.S. Olympic Committee’s Winter Division in Lake Placid, N.Y., and he has continued working with them since joining the ETSU faculty in August 2013.

Freelap USA: Periodization seems to be a controversial topic, and it often gets a lot of heat for having low amounts of research to support theoretical models. Could you get into the limitations and difficulties of using science or research in the real-world setting?

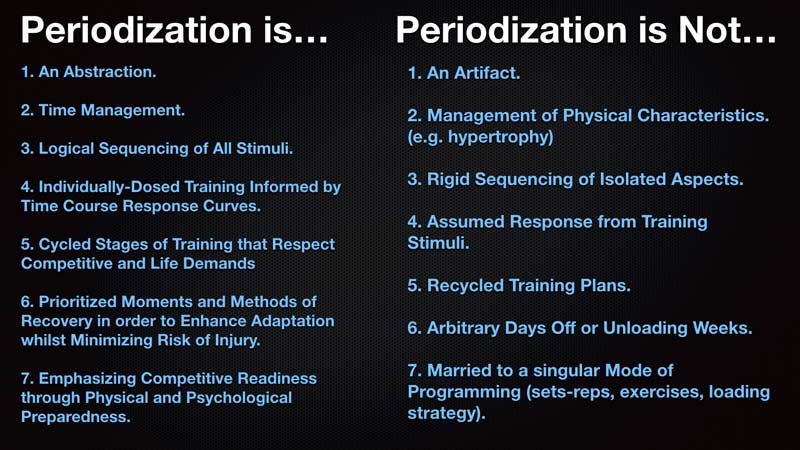

Brad DeWeese: Jumping right into the mix—love it! Yes, this topic continues to drive controversy, but most of the contention actually targets programming models and tactics, not periodization. This inadvertent misunderstanding fuels circular discussion and unwinnable debates, so it may be helpful to discuss terminology. Deconstructed to its most basic form, the term “periodization” literally deals with a partitioning of the time continuum.

Numerous professional domains outside of sport use this process of managing time, most notably history and the arts. Simply put, periodization allows us to look at specific moments in time so that we can make sense of our current state while being informed by our past, with an attempt to understand how it may impact the future. (Note that I did not say predict. This is not an aspect of periodization and is erroneously suggested by some sport theorists).

Periodization allows us to look at specific moments in time so that we can make sense of our current state while being informed by our past, says @DrBradDeWeese. Share on XWith that being said, “training-related periodization” is a concept that recognizes coaches are tasked with creating a training plan that maximizes the likelihood of their athletes’ competitive readiness. This readiness requires an acknowledgement that the training plan should be structured in a manner that permits the realization of all training efforts (neuromuscular, metabolic, skill, psychological) through a balance of work and rest.

As such, it is difficult to isolate “periodization” in a lab setting—we cannot simply remove a training component (e.g., weight training) for short-term study and expect to understand how this singular variable will influence competitive outcomes. True study of periodization is ecological and observational (think Jane Goodall), as this permits the observer to merge contextual matters with monitoring data that is collected along the way.

Freelap USA: People talk about RFD, but many simply don’t measure it properly. Can you go into the value of this metric and explain how you track it over a season or career?

Brad DeWeese: Rate of force development, often called explosive strength, is indeed a valuable metric that provides meaningful insight on the training process. Practically speaking, it is common knowledge that most sporting actions occur within a time frame too short for the production of maximal strength. As a result, how fast an athlete can generate high force is a competitive advantage. This has been well-documented as a limiting factor for both running and jumping (see the work of Ken Clark, Chris Sole, Per Aagaard, etc.).

With regard to how we assess preparedness here at East Tennessee State University, this variable is a hallmark of our monitoring system in both the isometric mid-thigh pull and jumping protocols. For instance, during the IMTP, we consider RFD at a few time points that are approximate to most athletic movements: 50 ms (CNS/“time to strike”), 100 ms (mixed bag/“sprint ground contact”), and 200 ms (muscle/“time to jump”). From here, we can make sure our training plans influence these metrics in the right direction and at the right times.

Specifically, we understand that basic strength training will drive the force curve “up and to the right,” which permits RFD to increase at all time-points by default. However, once an athlete has accumulated appropriate strength, being able to mature and retain optimal RFD becomes a priority. Hence, the training plan becomes more pragmatic and/or advanced, with greater saturation of strength-speed and speed-strength aspects that hope to influence early-stage RFD. Strength always underpins RFD capabilities, and it is true that we can never be too strong. However, consideration of critical time-points allows us to be intentional in prescribing training content that would provide greater relative benefit in improving performance in sport compared to pursuing further gains in maximal strength.

Freelap USA: Medicine ball throws are great teaching tools, and you have excellent results using the techniques of throws and sprints. Any details you can share for younger populations in the high school arena?

Brad DeWeese: You hit the nail on the head: Medicine ball throws are great TEACHING TOOLS. With anything “strength” related, it is easy to get consumed with the notion of increasing external load. However, the emphasis of medicine ball throwing should be placed on demonstrating “power” through optimal technique that is more likely to have positive transfer to the sport. Placing load ahead of technique (especially within a younger population such as the high school arena) removes an opportunity for the athlete to “feel/experience” proper body positioning, while also preventing the coach from seeing where movement “leaks” arise.

Video 1. Simple medicine ball throws are effective. Throwing vertically for height can improve the extension qualities of athletes when practiced consistently.

With regard to my personal approach, we place multi-throw and multi-jump exercises just ahead of our sprint session so as to: (a) rehearse the session’s primary skill and (b) provide a small overload with respect to the ground reaction forces. In short, the throws and jumps serve to potentiate an aspect of sprint skill. For example, we may place horizontal medicine ball “chest passes” onto a high-jump mat prior to block starts, while performing more vertical-oriented movements such as a medicine ball toss for height prior to top-speed efforts. This approach allows us to rehearse key movement strategies at multiple points within a practice session while saving true overload for the weight room through movements such as the weightlifting derivatives.

Freelap USA: Technology and data are sometimes difficult to add into a coaching program. How do you manage a balance so your program has a paper trail? What are some tips to help keep the process honest?

Brad DeWeese: We are at an interesting time in our profession. Perhaps resulting from the conglomeration of teams investing in sport performance, a saturated commercial market of sport science toys, society’s (sometimes blind) acceptance of “big data” and “convenience,” and the recruiting “arms race,” performance coaches face ambiguity on their ultimate role within a team setting. In a compulsive reaction often fueled by keeping up with their competitors, they attempt to add breadth at the expense of depth and true expertise. Though all elite practitioners have to strike a balance between the two, an oftentimes irrational fear of specializing in multiple domains is resulting in an underperformance within our house.

In a compulsive reaction often fueled by keeping up with competitors, S&C/performance coaches attempt to add breadth at the expense of depth and true experience, says @DrBradDeWeese. Share on XThat being said, I certainly believe and advocate for longitudinal monitoring so as to inform and fine-tune the training process. Furthermore, objective information demonstrating your efforts within athlete preparation is valuable evidence when working in an industry that continues to see S&C/performance coaches being fired as a means to justify and “correct” poor on-field performance.

However, I believe in elegance. In other words: (a) understand your sport, (b) determine variables that are manageable and actionable, (c) seek tools or technology that help you address these metrics in a manner that fits your time and budgetary constraints, (d) take small bits and be patient, and (e) work to develop interdepartmental collaboration within your organization. Meaning, as you begin to look at the information from GPS or a force plate, attempt to layer it with the contextual information that is observed by the complete support staff across the training process. Not only does this help a coach “learn the metrics,” but it also provides them with the ability to lead a deeper and more meaningful dialogue with sport coaches and/or athletes.

Freelap USA: You have a wealth of knowledge as a strength coach, track coach, and sport scientist. How do you juggle all three when working with bobsled? With the sport having so much need for speed and size with athletes, how can American football learn from this event?

Brad DeWeese: I have been extremely fortunate to wear many hats over the course of my career. Since day one in the profession, I have dually served as a track coach and strength coach at the same time, while also juggling miscellaneous supplemental roles in Sports Information, Compliance, and Sport Science, among others. Collectively, these experiences have allowed me to keep my eyes on the big picture, as opposed to staying too deep within one particular silo.

As it relates to bobsled, American football, or any sport for that matter, I typically take a step back and strip the activity down to its basic structure: “How far do they move,” “How fast do they move,” “How often do they move,” etc. Once dissected, it then becomes easier to put together a plan of attack.

Video 2. Plyometrics take time before they actually actualize or gel, so make sure you have a well-rounded program. Vertical force development in hurdle hops is obvious, but they actually help with acceleration as well.

Bobsled, for instance, is a “downhill” sport that essentially relies on a balance of strength and speed to provide starting momentum for the sled’s descent. From a training perspective, I treat these push athletes like short sprinters or just “heavier” 60-meter sprint specialists. As a result, we prioritize a complementary approach so that strength training supports the speed training, not vice versa. Specifically, we work under the guiding principle that chronic exposure to strength training (in various forms) will assist in the retention of optimal sprinting/pushing technique during the face of constraints that are either presented from the environment (running on ice) or internally related (fatigue).

Within American football, I continue to assert that dedicated speed training should be prioritized, as exposure to higher velocities (above game- and weight room-related speed) will provide a performance reserve, while allowing for enhancements in neural drive that we commonly associate with RFD.