“Say all that you want about periodization, about macrocycles, microcycles—or bicycles—which is about the only cycle I can relate to at this point in my 42-year coaching career. The fact remains that I run two meets a week for over eight weeks with runners who hate to train and complain about racing, yet somehow expect to run their best times and their brightest efforts at the biggest meets of the year.

If I get this done, I call it a motorcycle.”

There isn’t a high school or collegiate coach in the U.S. who doesn’t understand the concept of periodization. But there also isn’t a coach who can tell you, with certainty, that the approach they take guarantees the best athletes will peak for the most important competitions of the season.

This has nothing to do with their lack of knowledge or insight. They all have plenty of that. The reality is that high school cross country and track is just screwy. In high school, cross country meets may begin in August, just weeks after the season begins. Sometimes meets are twice a week. Coaches will tell you they are building for probably three main late-season competitions: conference, sectional, and state. The problem with that approach is that all three follow within a week of each other. Do we know for sure if what we are doing really does have our athletes ready for those meets?

A Two-Phrase Periodization Model: Foundation and Competition

Many coaches will assign phases to their periodization models, such as base phase, competition phase, peaking, tapering, restoration, and transition. I agree with those who simplify their approach to just two phases: General Preparation and Specific Preparation. I like to call this two-phase model, Foundation and Competition. Why? As a high school coach, I view “foundation” as what takes place in the summer after spring track, and “competition” as what most likely begins a week or so after school starts in late August.

What coaches often do—and it’s a good idea—is assign a priority to whatever competition they run beginning in late August. Some coaches describe meets as extended workouts where the goal is to “run through” the meet. They are building toward what they consider their top priority competitions. The top priority meets may be a conference, regional, or sectional for those who know that state qualification is out of the question. They know that it’s difficult to deliver strong performances one after another, and they may adjust training accordingly.

The fact that cross-country courses vary in terrain and distance can be both beneficial and problematic. Different courses can be used to explain time discrepancies, but when time and place are really the only variables for assessing an athlete’s performance, coaches can’t always tell if their training has truly accomplished what they anticipate it doing.

Some coaches like to assign 14 weeks as the point where the foundational phase switches to the competitive phase. I like 14 weeks just because it works for my cross-country season, which runs from early August to the first week in November. This is the reason I am intrigued by the use of Power Meters for training assessment. Instead of relying on a rigid timeline or times and distance covered during training sessions as the way to monitor preparation, I can make adjustments based on the specific data supplied by the power meters.

Power meters can give me the advantage of assessing what is going on with each of my athletes, which may not be exactly what my training timeline suggests it should be. The power meter lets me know how a hilly or curvy course influences a runner’s power output or running efficiency. The 3-D accelerometer gives me data on vertical and lateral movements—things that may change based on the nature of various courses. In other words, I have something to go on after a race other than just a time or place.

As Jim Vance notes in Run with Power, “Long term training history, fitness level at the start of training, injury history, weakness or physical limitations, motivation, confidence, and their factors all play a part in the training response. This is why a power meter is such an amazing tool: you’ll know how all these variables affect you, and know your training is addressing them.”

So, if I’m looking at summertime as the foundational period, I consider two things: first, my runners may be coming off a spring competitive track season, and second, some of these same runners will be entering summertime competition through a local track club. This can make any periodization plan more challenging. When do we do what we want to do?

Improving Foundational Abilities

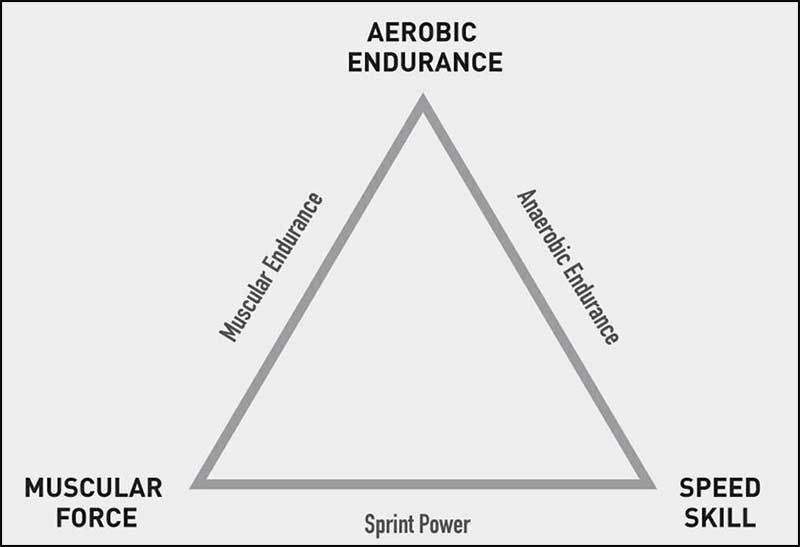

Joe Friel presents what he refers to as the “training triad,” the three specific abilities an endurance athlete must develop early on: aerobic endurance, muscular force, and speed skill.

If you are training to improve aerobic endurance, your workouts focus on things like stroke volume and capillarization, with the goal of getting more oxygen to the working muscles. Many coaches refer to this as LSD—long, slow distance runs—or moderately paced shorter runs, which should help the coach assess changes in running efficiency.

Why look at efficiency? What if a runner’s times aren’t faster? A power meter is the way to let the runner know if his or her efficiency is improving. As Vance points out, “If you are maintaining the same pace but seeing you are using less power to maintain it, that’s a strong signal of more efficient movement and aerobic fitness gains.”

But if you run faster, do those speeds affect your efficiency? We know that efficiency tends to decrease exponentially as speed increases. As a result, a power meter lets you know if you are pushing that point of decrease further out. As Vance describes it, “The more efficient you are in your aerobic endurance intensities, the better prepared you are as a runner.”

What about Friel’s next two points on his training pyramid—muscular force and speed skill? Muscular force refers to the ability of muscles to contract and apply big forces to overcome gravity. Strengthening both the legs and the core—and by core, I mean everything from the upper leg to the shoulders—is a way to improve muscular force. We do things like kettlebell swings, goblet squats, and trap bar deadlifts over the summer.

We also do hill sprints and short, high-speed flying start sprints. I like 75 meters, but some coaches prefer much shorter distances. Here again, a power meter will show you if muscular force is improving. If your cadence hasn’t changed, but your power has increased, your force production has improved. The bottom line: higher speed and greater force means power is improving because power is force times speed.

The third part of the Friel triangle—moving at a high rate of speed—is what improves power. Jim Vance notes that speed is the “most precious resource a runner can have, and so it is arguably the most important skill you should train.” As distance runners get faster, their efficiency at slower speeds increases, but Vance make it clear that efficient runners don’t win races—the fastest runners do.

Developing Competitive Abilities

Once the foundational training has addressed aerobic endurance, muscular force, and speed skill, athletes can begin to develop muscular endurance, anaerobic endurance, and sprint power. Friel refers to these as “advanced abilities.”

Muscular endurance is a matter of big forces applied over a longer time. Coaches have historically addressed this by way of tempo and threshold runs. Even for these, power meters can help by letting a runner know if he or she is improving or maintaining efficiency at faster paces.

Anaerobic endurance combines aerobic endurance with speed skill. Near maximal effort—what describes our ASR workouts—will improve aerobic capacity, which is more generally referred to as V02 max. Coaches address this by having runners train at the V02 max level on their training tables. A power meter can assist here as well. A good indication of improvement is an increase in efficiency in the V02 max zone.

Sprint power is at the base of Friel’s performance pyramid. The speed in meters per second is a good assessment, but power meters will even indicate peak power output, which has an additional motivational benefit. Of course, sprint power is not what Arthur Lydiard would have incorporated into his training pyramid, and I can understand why coaches would view high speed as high risk. I haven’t experienced this risk aspect so I agree with Vance, who believes that the higher the max power you can produce, the higher the ceiling you have as an athlete.

But the question still remains: Can power zones tracked by power meters really help athletes run faster, or is this just a sophisticated data generator that simply confirms what coaches already know? I like what Vance suggests: “Certainly, they have the potential to create a breakthrough in training and performance. But the technology is so new that it is hard for us to say definitely that training by power meter is the best way to train.”

Power Meters Provide ‘Golden Feedback’

My bottom line is this: I like to be on the cutting edge of training approaches and new technologies, but as Mel Siff once reminded me, “If you’re always on the cutting edge, you’re holding the knife the wrong way.” In this regard, I need to work these accelerometers into my training on a more consistent basis before drawing more definitive conclusions. However, I also agree with Vance that the best coaches are the ones who innovate, and who devise training sessions and periodization plans that meet the individual needs, strengths, and weaknesses of the athlete on a regular, daily basis.

This is the reason I agree with his insights on the possible benefits of power meters. Athletes know the exact type of training they need to target, they know the specific pace they can execute, and they have a clear picture of how efficiently they can run at that pace. They also know how effective their training is in terms of improving that intensity and pace. Vance calls this the “golden feedback” of power meters.

I also don’t see the use of power meters as deviating from what coaches are currently doing. Most will follow a Jack Daniels formula, and that’s been a significant part of my approach to training since 1979. And most coaches would look at the realities of their situation the same way I do: end of track, summertime, and fall cross country for 14 weeks. Coaches are generally happy with the results when they apply a Daniels-type block approach—or some derivation of that approach—during the foundational and competitive phases of their sport. If they weren’t happy, they would make some changes.

The real value of power meters may be in the kinds of assessments that accelerometer technology can provide. For example, I can analyze the progress toward peaking for a couple of key races in late October and early November on something other than what I currently review: finish time and where my runners have placed overall. If a training objective or race time is slower than what I and my runners have anticipated, I have variables in addition to things like course complexity, weather, injury, or overall physical health to explain that.

Author’s note:

I have both RunScribe and Stryd.

RunScribe is heavy on locomotion information, and perhaps that’s why others have described it as more of a mobile running lab than a training tool. It provides a wide range of biomechanical data in addition to pace and cadence.

Stryd provides data on power, efficiency, stiffness, and speed. I can analyze cadence, vertical motion, and upper body movement. If runners can effectively change these to become more efficient, their running economy will improve.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

Dijk, J. C. Van, and Ron Van Megen. The Secret of Running: Maximum Performance Gains through Effective Power Metering and Training Analysis. Aachen, Germany: Meyer & Meyer Sport, 2017. Print.

Friel, Joe. The Power Meter Handbook: A User’s Guide for Cyclists and Triathletes. Boulder, CO: VeloPress, 2012. Print.

Vance, Jim. Run with Power: The Complete Guide to Power Meters for Running. Boulder, CO: VeloPress, 2016. Print.