Too many people complicate their conditioning work and intervals by trying to get their athletes into the “fat-burning zone” or train at their lactic threshold, etc. The only thing is, those will be different for different people, and each prescribed interval session has a different effect based on how fit your athletes are at the time.

As a university strength and conditioning coach, I have to write conditioning programs for six different sports (12 teams). I dove into the research, read many books on the subject, and thought I was an expert in cardiovascular health and improvements. Then I tried to apply these specific protocols with the different teams, hoping each team would increase their fitness to the specific level required by their sport.

Do you know what happened?

Not that!

The prescriptions were too confusing and too hard to follow. I tried individualizing their conditioning work using the Maximal Aerobic Speed (MAS) protocol by basing their distances and interval times off their most recent fitness testing scores (Yo-Yo, mile run, Bronco, etc.). Most athletes didn’t do the workouts at all or just went for a 5-kilometer run instead. So, after all that hard research (which is great knowledge to have moving forward), at the end of the day, simplicity wins (Keep It Simple Stupid—KISS). Shocker.

At the end of the day, simplicity wins. I now prescribe minute intervals as conditioning for both my athletes and my non-athlete clients, says @chergott94. Share on XWhat I have settled on now, especially in-season for our athletes as a measure of top-up to their fitness levels, and what I prescribe to all my non-athlete clients are minute intervals. Short, to the point, and deadly.

How It Works

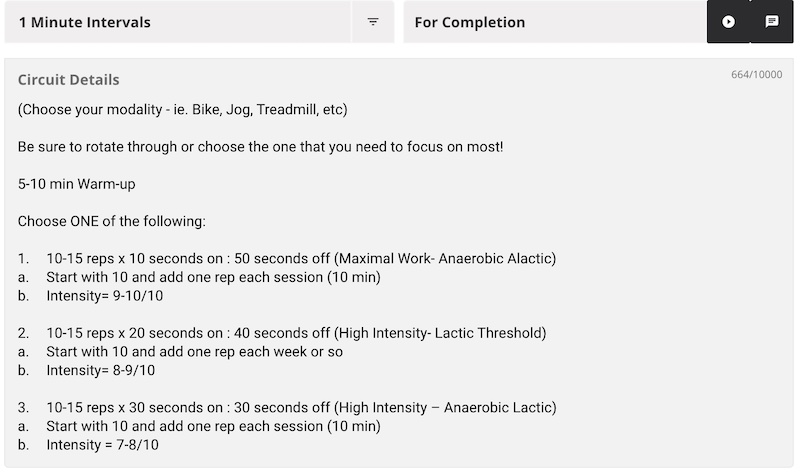

There are three protocols.

- The first is very high-intensity work with longer rests (anaerobic alactic). The athletes push as hard as they can (maximal effort) for 10 seconds. Then they rest for 50 seconds (the remainder of a minute) and repeat for the number of sets you want for them (more on that later).

- I recommend most of my teams hit the bike for this sort of protocol, as they can push harder on a bike than if they were running outside or on a treadmill. Regardless of sport (rugby, soccer, basketball, etc.), it gets them off their feet and hammering the intervals as hard as they can.

- The second is high-intensity work, but starting to hit that lactic feeling in their legs that many sadistic folks crave. They push hard for 20 seconds and rest for 40 seconds. Repeat for the number of intervals you want.

- These are really easy to run in a shuttle fashion. I often get my athletes to set a distance (e.g., 10 meters) and run back and forth as many times as they can in that time. That way, they get some change of direction work, reducing hamstring injury risk (instead of sprinting all-out for 20 seconds in a straight line).

- The third session is for sure giving them jelly legs as they push moderately hard for 30 seconds, then rest for only 30 seconds before repeating. So, the work isn’t as high as the other two, but the rest is shorter to compensate.

- I recommend my teams hit the bike, or they can shuttle these as well. These intervals could also be done as hard tempos, but once again, for the sake of the hamstrings, a shuttle is best (e.g., 10m–20m) or hitting the bike.

As you can see, each interval adds up to a minute (hence the name). I love these intervals for many reasons, but the simplicity of the timing is great because even if the athletes don’t have a timer app on their phone (which everyone does nowadays) or they forgot their phone altogether, they can simply look at a clock, watch, etc. and easily keep track of the time.

Second, they can do these on any equipment they have—rower, bike, treadmill, stair climber, jog outside, shuttle runs, etc. Any and all modes of cardio equipment will get the job done. As mentioned before, having athletes hit the bike allows them to push harder, which is more beneficial for the 10:50 protocol while also reducing the joint stress for impact sports (soccer, rugby, basketball).

Sprinting is good for conditioning and is obviously more “sports-specific” for running sports. Still, as mentioned above, I recommend putting these into a shuttle format so that athletes aren’t just all-out sprinting for 20–30 seconds (which would be close to 200 meters). This will reduce hamstring injuries for sure, and if there is one thing we all know, if an athlete gets hurt doing your conditioning work, that is bad news for you!

Next, these minute intervals are very easy to start with for programming. As for the specific number of intervals, I usually start my athletes off with 10. It is a nice round number, and that also means it only takes 10 minutes to complete (which doesn’t sound that intimidating until you are four intervals deep and have six to go). Another reason I love the simplicity of the format is that the athletes can just do as many intervals as they have time for. If they only have five minutes to hit conditioning after their lift, they just do five. It’s as simple as that!

Lastly, progressing the intervals is a very straightforward process. An easy way is to simply add a rep each week or so. So, week one, you do 10, week two, you do 11, and so on.

You can also play around with which option you prefer based on their training schedule. If they do their conditioning work three times a week, you could do the 10/50 on Monday, 20/40 on Wednesday, and 30/30 on Friday. Boom! Simple.

Now, if they only do conditioning twice a week, they could still rotate through by hitting 10/50 on Tuesday, 20/40 on Thursday, and then 30/30 on the following Tuesday. This would lead them back to the 10/50 that Thursday. That way, they still hit all three interval sessions, but they are just spread out more.

Which Methods Is Best for Me?

This is a question I often get asked by my athletes and clients; as always, the answer is that it depends. Primarily, it depends on what area of their fitness is lacking the most for your athletes individually.

- Do they get tired easily at the beginning of a high-intensity shift or play? Then maybe ramp up the 10/50 protocol, so they have the alactic capacity to push each time.

- If their legs get that burning feeling after only 10–15 seconds of work/play? Then give the 20/40 a go to try and push that feeling until later so you can perform more optimally longer by pushing your lactic threshold a bit higher (increase lactate clearance ability).

- And lastly, if they find that halfway through their shift or by the end of the shot clock they are gassed, then the 30/30 will help with that by increasing lactic tolerance. (Because after a hard 30 seconds, it will build up, but we want to make sure they can push through it.)

As you can see, there are many options for progress and variability with the minute intervals, which is why I like the method so much. At the end of the day, each of these will give your athletes a killer session—they won’t enjoy them much (sorry), but they will give them the fitness levels and cardiovascular gains they seek.

So pick your modality, pick your option, and get after it!

Peace. Gains.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF