With all of the fanfare lately regarding isometrics, it seemed only appropriate to write something up on why the isometric squat test is gold, and why isometrics need to be programmed smarter. Whatever your goals with training, this article will likely overlap some of the pain points of training groups or beginner athletes, and it may help your elite athletes break plateaus in training as well. If you are a fan of isometric training, this article can spice up old workouts while sharing new methods of training and testing, including the isometric belt squat.

I personally find isometrics useful only when prescribed with precision, and that means knowing the purpose of the exercise and how to do it perfectly. I go over some science, the rationales for testing, and a few workouts to cover the bases. While this article is focused on isometric training of the legs, it’s also a great primer on isometric training in general.

Isometric Training – Too Much of a Good Thing?

I don’t program isometrics much mainly because they are boring. Without biofeedback, isometrics basically tell athletes to have a movement timeout and require blinded effort. While physiologically, a muscle fires at high velocities during isometric training, athletes are basically frozen in time and not able to visually express their abilities outside of grunts and duration. Isometric training is great for teaching joint angles and body positions—basically sculpting athletes to be in the right posture—but not great for athleticism in the real world.

Isometric training is great for teaching joint angles and body positions—basically sculpting athletes to be in the right position—but not great for athleticism in the real world. Share on XThough I don’t find watching an athlete do something stationary very thrilling, I do follow the research and records, and I believe that including isometrics from time to time is worth the effort. If it wasn’t for Christian Thibaudeau and his work from 20 years ago, I would likely not have appreciated the value of isometrics done the right way. While I was interested in what Giles Cosmetti and other earlier experts were doing, Thibaudeau added an edge that made isometrics relevant.

Recently, a rush to fall in love with isometrics started because of need. When maximal loading to the body is a scarcity—literally a severe challenge with COVID-19—isometrics have been seen as a replacement. Isometrics are not the same as dynamic loading, even temporarily, and an individual can’t become a world-class bodybuilder or athlete from isometrics alone. You can do far better with plyometrics, sprinting, and conventional weight training.

So why use isometrics beyond teaching? Well, the physiological benefits of isometrics are great for assisting athletes, but more importantly, isometric testing has an advantage with athletes when they need to be assessed. I will talk more about neurophysiology later, but I want to cover the practical coaching benefits of isometric training now before heading to specific testing and training of the legs.

Bringing Isometrics Back into the Spotlight

Isometrics are valuable, and I have spent a lot of time promoting them, but they are now entering a stage of exaggerated claims and alleged results of mythical proportions. Isometrics, specifically with healthy athletes, are very limited in application and effectiveness for dynamic activities. While they are valuable and part of a program, if you never do isometrics, I don’t think any athlete will fail to reach their potential.

So why commit an article or two to promoting them? Well, the most important benefit of isometrics is not the training itself, but the teaching and testing qualities they provide. You can get very compelling improvements to the human body from extreme isometric efforts, but frankly those changes pale in comparison to the dynamic actions of resisted exercises.

If I had to make an argument for isometric training and testing, it’s really about changing things up and safety. Technically, anyone can get hurt doing anything, but the risks with isometric training are usually lower than with dynamic activities. Here’s why isometrics are potentially a great fit for your program.

Technically, anyone can get hurt doing anything, but the risks with isometric training are usually lower than with dynamic activities, says @spikesonly. Share on XSafe for Athletes: I am not going to oversell isometrics as worry-free. Extreme isometrics are extreme forms of training, and they may pose some risk if not done right. On average, maximal effort isometrics tend to be less risky than their dynamic counterparts.

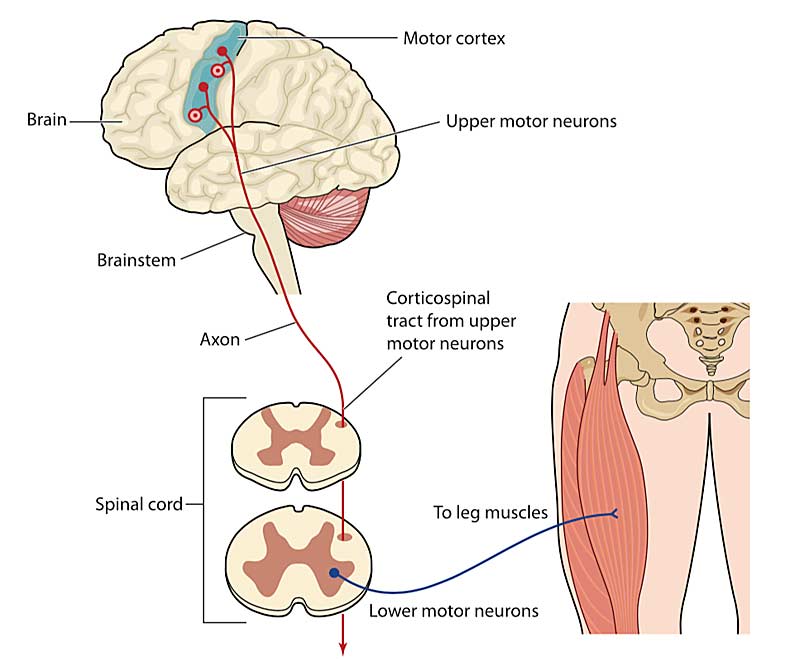

Neuromuscular Qualities: Using isometrics properly, coaches can tap into the target brain centers for the right adaptations for athletes of all levels. Teaching an athlete to use their nervous systems to recruit maximally is a valuable lesson and skill for later development.

Testing Benefits: Isometrics help reduce noise in testing and explain the safety qualities of the contraction. Testing has caveats, as the nature of static contractions and training carryover has limits with dynamic activities.

Challenging to Athletes: Biofeedback enables an athlete to see their outputs in real time, encouraging them to give a better effort. Along with biofeedback, athletes of all levels like isometrics because they tend to be less sore afterward.

Now the question most coaches will ask is: How does all this connect to squatting patterns? Before explaining why I don’t like wall squats or how to set up a rack for single-leg training, it’s vital that coaches take isometrics seriously and not see them as finishers or ways to spice things up in training. If you are going to use isometrics in training, make them count; don’t demote them to entertainment purposes only. The reason I think isometrics are picking up steam is mainly due to how they are glamorized scientifically by coaches, and much of the information shared is either borderline science fiction or just inaccurately depicted.

Necessary Neurophysiology and Biomechanics of Isometrics

I will be upfront and tell you that isometric training alone will not elicit the benefits that dynamic movements bring about, but it’s more about how adding it into a program can help. Coaches should know that using isometrics in training doesn’t give athletes the same stimulus as dynamic contractions that include both eccentric and concentric activities. True, it’s very hard to remove a contraction type from training, as a strength program heavy with isometrics won’t offset a hard practice with a lot of decelerations (eccentric load), so theoretical ideas usually die on the vine. What you can do is at least improve your strength program as much as possible, and that means using any technique that enables constant improvement over time.

Isometric training alone will not elicit the benefits that dynamic movements bring about, but it’s more about how adding it into a program can help, says @spikesonly. Share on X

When designing training, especially with isometrics, think about the hypoxic environment, targeting the brain, and relevant anatomy. Those three areas are hard to fully grasp, as the science isn’t exactly crystal clear on what happens in training. We barely can make conclusions now on what actually happens during simple tasks, never mind complex movements. The effort, duration, joint angle, and style of contraction make isometrics more than just holding a position and hoping for the best. Clear differentiation between a ramp style (gradual rise of intensity) and a ballistic effort (rapid and short duration) is visually difficult to decipher. Thus, coaches should shy away from treating isometrics like a second-class citizen and being lazy with programming.

In a provocative study, researchers looked at three styles of potentiation for sprints using isometrics and dynamic contractions. With even more granularity, they compared acceleration data with single joint and multi-joint contractions that were either isometric or dynamic. What was interesting was that the three protocols were not much different in performance, leading the researchers to conclude that just incorporating any potentiation is effective, regardless of the type of contraction and the amount of muscle stimulated. While the data is not enough evidence to make strong conclusions, it is thought-provoking enough to make me wonder how much global versus specific training matters to an athlete.

Transfer to the field matters—I understand that and also remind coaches of the dangers of only focusing on the specificity of sport training. A wise approach to handling the question of “what to do” is to ask if something either correlates (has a relationship) or actually causes (creates) an improvement. Similar to causation versus correlation arguments, testing versus training becomes an issue from time to time because some tests are great for supplying information, but they are not always good exercises for training.

Isometric squats have been used like isometric pulling to identify athletic performance in Rugby Union, so the activity has value to coaches. My recommendation is to use them sparingly, as maximal effort in dynamic squatting is likely a far better option in the long run for training. Therefore, testing the isometric squat should not be more than a quarterly approach if time is everything in a setting.

Gross body patterns without movement enable an athlete to really push their body to the limit. Based on the science, remember not to get lost down a rabbit hole and put too much time into isometrics. I have not added much isometric training to my program over the years; I just tend to use it sparingly with more precision now.

Still, if you are going to use isometrics, do it right and make sure you have a purpose. Enough science exists to include in the program, but getting carried away and spending too much time on them—the majority of the work out, for example—won’t really help athletes.

Isometric Testing – Why the Belt Squat Reigns Supreme

Controversially, I favor using the isometric belt squat over the IMTP (isometric mid-thigh pull) for several reasons. Don’t get me wrong: I am a huge fan of pulling a bar because more athletes need to appreciate how a simple barbell will help their careers. As I mentioned earlier in my Olympic lifting article, gripping a bar is a handshake to the commitment of conventional lifting.

Having a bar in both the Raptor test and the IMTP is a subliminal message that barbells can fix a lot of problems. Tying maximal strength to a barbell is not a sin; in fact, it’s more important than ever in a world where time and effort are scant for modern athletes. Using a belt squat does slightly compromise testing, but not enough to deter a sport science team from employing the assessment of peak force. Based on what we know about dynamic belt squats and isometric belt squats compared to barbell activities, they are a valuable option for coaches and sport science teams.

Based on what we know about dynamic and isometric belt squats compared to barbell activities, they are a valuable option for coaches and sport science teams, says @spikesonly. Share on XThe main arguments against the belt squat test are hypothetical, as anyone committed to data integrity will adjust their protocol to eliminate testing error. I have seen many conjectures as to what could go wrong with the test, but when directly asked about the same issues with the IMTP and bar squat alternatives, I usually get silence. If you slow down and look at the test, you will see that the point of the dual force plates is for a chain to pass through the legs and to the middle of the pelvis. Right and left symmetry is nice to have, but most screening programs have hop tests and other reference points to work with. If performed properly, an athlete will likely not shift their hip, and if they do, it’s for good reason.

Video 1. The isometric belt squat test is a great option due to the simplicity and cost factor of using lower-priced instrumentation. Remember, peak values are fairly easy to collect, but don’t scoff at RFD, especially when combined with speed and jump testing. Coaches only need a few 2-3 second efforts to condition the athlete before hitting a full testing duration.

The primary issue I have is continuity of testing over time when injuries occur to athletes in sport. Many maximal strength tests are essential for speed and power athletes who are in collision sports. American football is a sport of attention, and hand, wrist, elbow, shoulder, and spine injuries are common and make the IMTP challenging or impossible. When you add in the fact that you can keep the setup the same without changing stations, a single set of force plates can be used more efficiently. It is perfectly fine to do the isometric squat using a bar on the shoulders with some populations, but comfort is the most important factor in sports where culture doesn’t gravitate to barbells, so I prefer not using a bar with populations that are not already lifting heavy.

Last is interpretation of the belt squat, since dynamic and barbell-based options will need to be considered, as comparison is natural. The most important point I will make is that the goal of the isometric belt squat is to safely get an appraisal of the athlete’s maximal force capabilities. If the test is not ergonomic, athletes will simply provide limited effort and only express a small representation of their abilities. While I love weightlifting as part of training, most exercises are limited in transfer, as the skill component creates an impairment to tapping into true maximal efforts. Still, we can conclude what an athlete likely needs in training by looking at the information from both training records and the isometric belt squat test.

We can conclude what an athlete likely needs in training by looking at the information from both training records and the isometric belt squat test, says @spikesonly. Share on XExercises and Activities That Are Worth Trying

Now that you have read the science and testing background, I will share some exercises that may help support your training. Isometric squatting has both training and testing value, but the list below is the cream of all of the exercises I prefer. Keep in mind I mentioned other exercises earlier with my reference to the top exercises, and I casually list other leg isometric exercises in past and future articles. I personally don’t like using isometric split squats for testing because it adds another degree of complexity and takes more time to set up. We still appraise split squats, but the test is not popular with coaches and becomes difficult to prescribe with other lifts that are bilateral such as the Olympic variations.

Some exercises are not squatting patterns at all, but I decided to include them because they help develop leg strength. Notice that I didn’t include any isometric pulling, as I don’t want coaches to be confused with what the intent is with their athletes. Please don’t swap out similar exercises blindly and try them out first so you can experience what it’s like to do them. Also don’t stress out if they are not pure isometrics, as some of the exercises do have small ranges of motion.

Before I toss a few exercises your way, make sure you are familiar with the concepts of yielding versus overcoming and ramping versus burst-style contractions. The small nuances of lifting or holding a weight will make a big difference, and you should understand that squatting patterns are harder to incorporate biofeedback into than pulling exercises or pushing movements.

Acceleration Split Squats

Angled split squats are great for those needing a change and a way to add plantar flexion stimulation. Technically, the calf does get activity and strain during conventional squatting, but when athletes are in an acceleration position, they recruit with more specificity than with flat-footed movements. I have seen scrum-style tests in rugby that are similar, but I prefer a tether and belt harness for the most part. In addition to the setup, the use of a ramp contraction for longer durations is popular because it buys time to teach posture and joint angles. You can do this exercise with a heavy sled and partner and with various stance phases of acceleration, since it replaces the old wall drill in many circumstances.

Video 2. The acceleration split squat is really a single-leg emphasis of the rear leg with the front leg used for balance. You can use wedges and even track blocks for better force production of the hip extensors, but using nothing but the ground will likely be more effective for transfer.

Deep Squat Pulses

Using a belt squat, short rapid bursts in a deeper joint angle are a nice way for athletes to fire out of the hole if they need a way to either get out of bad habits or contrast their training. Most who use pulses are trying to end their workout session with a “finisher” that has purpose and usefulness, but some coaches see a benefit with using it to prime workouts or pair it in training. I personally use it more now because of the popularity of isometric belt squat testing. This is one of the few exercises where I find RFD (rate of force) potentially useful for biofeedback. Due to the short contraction, absolute peak force is often difficult to attain so the exercise contraction type isn’t exhausting.

Deep squat pulses are one of the few exercises where I find rate of force potentially useful for biofeedback, says @spikesonly. Share on XVideo 3. With links that are either color-coded or numbered, the setup can be a breeze for busy coaches. You don’t have to number or code all of the links—just a few of them if the chain is designated for the exercise.

Potentiation Partials

Shallow or quarter squats are fine for both dynamic exercise and isometric options. Due to the mechanical advantage of shallow squats, adding hundreds of pounds to a squat rack is a burden, so I prefer locked options such as harnesses and pin presses. Some coaches like going through the continuum of joint angles in one session, while others use this as a way to potentiate and contrast with hurdle jumps. I like both, but I have used partials as a way to make hurdle hops more effective, and I tend to see benefit with technique. If an athlete is reinforcing joint angles, they tend to have a good reference point if you give them hints that are recent. You can do partials for squatting as a warm-up, but for me it’s specific joint angle reinforcement.

Video 4. Similar to squat depth reliability using chains, mark the chains properly for quarter squats and make sure the angle is repeated. A brief pulse or burst is useful for athletes to either potentiate or to wake up athletes for other exercises later.

Stork Stance Bursts

Coaches can use stork stance squats for rehabilitation or for testing, depending on their needs. This exercise is similar to the step-up, and some clever coaches have used elevated blocks to create a more sprint-like test. Due to the nature of the test, many coaches use squat racks instead of harnesses, but that is up to you and your situation. The most important principle is to make sure the testing is reliable and give feedback with sensor technology so the effort is maximal. You can use medical enhancement products like electrical muscle stimulation and blood flow restriction if needed.

Video 5. The main difference between the acceleration split squat and a stork stance is the body lean and the hip flexion of the non-support leg. This exercise can be made into a test or just used as a way to help with early rehabilitation.

Roman Chair Isometric Holds

I included this exercise because I feel that isometric hamstring strength is nice to have in specific situations. I am not saying that this is a great exercise for injury reduction or even performance, but it’s a good bridge to help drive all of the hamstring training upward. I have seen some variations that look like leg chops in a supine position, attempting to create an extreme isometric burst from the landing, but I would rather keep the specificity with sprinting for now.

Video 6. It’s hard to define a true Roman Chair, as it can be a flat back hyper or a GHR machine for all practical purposes. You can add load and hold type protocols to the exercise or resist against a fixed cable or similar. I don’t see this as an injury reduction exercise, just a progression to build to other movements.

Nearly all the exercise can be done without much more than a harness and chain but adding in technology such as load cells and even electromyography helps with biofeedback and/or record-keeping. Those who incorporate blood flow restriction (BFR) or electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) will likely see more success with the exercises depending on the goals and the phase of training the athlete is in. Generally, I don’t add BFR or EMS unless athletes are injured.

Tap into Maximal Intent Safely

With all the talk about velocity-based training and the sudden rise in sprinting popularity, it’s strange that I would write an article that literally has no speed or movement. Any coach or athlete can relate to failed attempts to move an impossible object, but the lesson is about effort and the body. Isometrics are great options when used sparingly, and I recommend coaches use them from time to time when athletes seem a little flat or in need of a change. Sometimes a spark in training isn’t really finite—it could be like turning on a switch when athletes are trying to do too much, such as a ballistic activity that has coordination demands.

Isometrics are great options when used sparingly, and I recommend coaches use them from time to time when athletes seem a little flat or in need of a change, says @spikesonly. Share on XWhatever your needs, consider isometric training and try the isometric belt squat test as well. The article should be enough to take a stab at isometrics, but don’t just limit yourself to the above information. Try taking it further and see where that guides you.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF