[mashshare]

The Bulgarian split squat is here to stay, but if it’s going to be a staple in your program, your athletes need to do it right. Lately, due to a rapid rise in its popularity, a rush to follow the trends in training has left many young coaches unaware that there are specific details to split squatting that they must follow.

In this article, a set of key principles of split squatting will guide you to better technique and better transfer to sport. It doesn’t matter if you use the Bulgarian split squat as an assistance exercise or a core lower body lift, anyone doing the exercise will see better gains in strength and power after reading this article.

Before You Start Split Squatting Heavy or Fast

The reality with sports training is that nothing is perfect for everyone, and while the split squat is popular, it’s not a magic bullet or movement without risk. Some coaches have attacked it without a shred of evidence to support them, while a few coaches defend it blindly. Again, all exercises have pros and cons, and it’s up to the coach to match split squats with the right athlete for the right reason.

It’s up to the coach to match #SplitSquats with the right athlete for the right reason, says @spikesonly. Share on XIf you read our earlier split squat and lunge article, you may wonder what is left to know about Bulgarian split squats, and the answer is we just scratched the surface. Watching really polished lifts from expert coaches is not the same as watching an intern or apprentice coach parrot vague cues to a watered-down movement. Perfecting the Bulgarian split squat isn’t about trying to make it more suitable for more athletes—it’s knowing when another exercise makes more sense or when to sequence it in training.

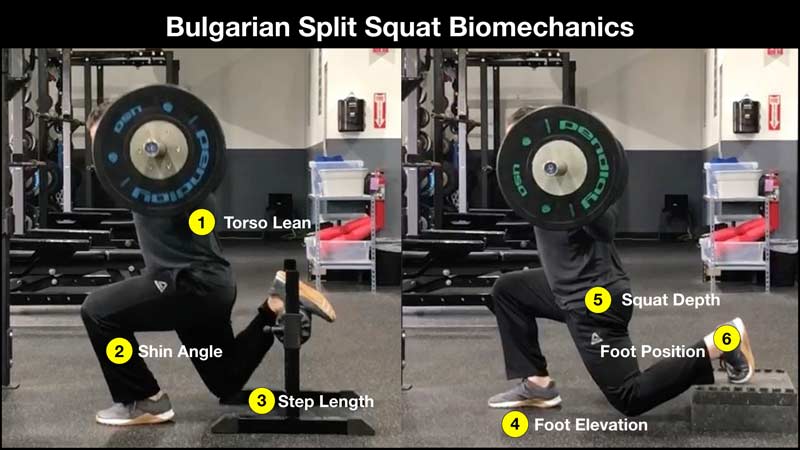

Video 1. A small box may be necessary if athletes find the split squat stand to be uncomfortable. Subtle adjustments in depth, stride, torso lean, and even foot position can change the exercise.

The most important takeaway besides the fact that details matter is that physics matter, not just what the exercise looks like. The lack of understanding of basic high school physics shocks and appalls me, and when you add in a human body, biomechanics plays a more complicated role. Instead of dumbing down a movement, it’s better to upskill a coach with better education.

It’s easy to simply skip the effort of polishing a movement and push forward, but results and risk change as the load increases. Remember: Progressive overload will eventually rear its head, and if you don’t start right, the end won’t be pretty. I have seen plenty of nagging injuries or stalls in training with athletes who were rushed through the training process, and what we have below is the culmination of working with great coaches and athletes.

Individualize the Movement by Screening Athletes

Screening athletes isn’t only about risk analysis—it’s knowing more about your athlete so you can program with high-definition precision. Don’t see screening as what could go wrong with an athlete on the field; view screening as what you can do better in the weight room or on training grounds to make training better. You should see movement screens as unloaded training competency tests, not part of a quest to find dysfunctional patterns.

When looking at an athlete who needs to perform the Bulgarian split squat, it’s logical to look at past injuries or range of motion tests, but it should be about whether an athlete can demonstrate proficiency in the weight room. Does the athlete split too far because they can’t decide with confidence? Does the athlete rotate their pelvis when they elevate their foot? Does the athlete shift forward or do they lean too much when they load heavy?

As you can see, the lift, like the traditional back and front squats, requires a lot of attention beyond sets and reps. When screening the athlete, simply include enough of the exercises they are likely to perform, as that information is priceless. Great movements have ground reaction forces, as most sports require a foot to hit the ground to make a play.

As with traditional back and front squats, a #BulgarianLift requires attention beyond sets and reps, says @spikesonly. Share on XBased on experience, most of the choices come from a past history of turf toe or similar, and from flexibility around the hips. An athlete may not seem to be a good candidate on paper or they may look like an ideal candidate during screening, but when the rubber hits the road, they either perform great or the exercise is not compatible. Coaches will see similarities between the requirements of performing the jerk exercise and the Bulgarian split squat, for obvious reasons. The main difference is that the Bulgarian split squat is elevated, and this is an issue if the athlete is wide and using a stand that’s too high.

Use the Correct Stance, Optimal Depth, and Weight Shift

When educating the athlete on ways to do the lift better, a few things to consider are stance, depth, and weight application. Athletes who use bilateral squatting are likely to have their feet greater than shoulder-width apart, but in the Bulgarian split squat the width is narrow—about as wide as the hips.

One of the strengths of Bulgarian split squats is the movement doesn’t change as much as the load increases, so tracking progress is easy. With squats, some athletes go wider so they don’t travel as far in the lift, and that is a legitimate problem with testing. The greater contribution of hamstring activity is the reason many coaches have incorporated the exercise into their program, but a conventional squat with Romanian deadlift is actually more effective for muscle recruitment because the quadriceps are less involved with the split squats.

Depth is a tricky decision because most coaches assume that single leg exercises have different rules than bilateral lifts. Single leg lifts play by the same rules as bilateral lifts. If an athlete has a problem with squat depth, having them split squat doesn’t really solve their restriction.

If an athlete has an issue with squat depth, having them split squat doesn’t fix their restriction, says @spikesonly. Share on XChanging the torso lean does change the spinal demand of the exercise, but it compromises the point of the exercise—unfolding and folding the body. A vertical front tibia, rear femur, and vertical torso do unload the lumbar region, but avoiding spinal loading altogether will always come back to haunt you when jumping and sprinting, as the spine will eventually have to be prepared to perform. The key to spinal loading is to manage it like any load, not to avoid a normal part of human motion.

Use the same depth as the conventional back squat but not more, and make sure the range of motion of the hip and recruitment is not straining the pelvis. True pelvic torsion is likely difficult to measure, but years ago at the Boston Sports Medicine and Performance Group Conference, Dr. McGill did mention potential injury. I am not worried about torsion because we use the rear leg as a balance point, not a contributor to force production. Split stances from jerks and bilaterally grounded split squats are a different story, but the angles are different than the Bulgarian split squat.

Video 2. Just because an athlete squats with one leg doesn’t mean that injuries can’t happen. The depth of a squat depends greatly on pelvic architecture, so make adjustments to the exercise based on anatomy.

Weight shift isn’t easy to visualize or explain, but most coaches use cues that lead an athlete to move their pelvis up and down nearly vertically. Most injuries in sport don’t come from vertical loading performed with a static foot position unless it’s a rapid lunge to save a play. Athletes need to feel the lift like they do with a bilateral squat, just with one leg doing most of the work. If they are not feeling it in the hip, they are likely not leaning; thus, the exercise is now limited.

Setting Up the Squat Rack and Using Split Squat Stands

One point that I should make is that if you are not risking failure, you are not fully challenging athletes to get better. I operate with the philosophy that all athletes deserve to be their best, so we should not design programs to bring up the cream and let the rest just get in a “good” workout. The reasons that an athlete misses a rep are obvious points to think about, but if no risk of completing a rep exists, then the load just babysits the athlete and actual strength development is missing. It is a cardinal sin to allow athletes to depend on box or ground feedback in any type of squat technique instead of kinesthetically knowing the placement of their body in regard to space and time.

If you are not risking failure, you are not fully challenging athletes to get better, says @spikesonly. Share on XA program can use balance pads and boxes to help remind athletes of depth, but it can’t perform a coordinative lobotomy. The difference between good biofeedback and dulling the athlete’s abilities depends on the amount, and timing, of measurement used in training. If an athlete needs to contact with rack, box, or ground to know if the rep distance is right after weeks of training, they are not being coached—they are merely being supervised. The purpose of the rack is safety, not to remove the effort of reinforcing depth or loading accurately.

Split squat stands are now a staple, meaning nearly any gym worth its salt will have a way to elevate the rear leg safely. Using a bench is possible, but a low box or a committed piece of equipment is the best practice with elevated split squats. When setting up the stand, make sure it is high enough for tall athletes and low enough for shorter athletes. Too low and the athlete can’t get deep enough; too high and the rear leg will torque the spine obliquely.

Check Bilateral Symmetry and Load Distribution

Right and left symmetries are about capacity and fatigue, and of course context if an imbalance exists. Some athletes do fine for years without addressing normal imbalances and some require high amounts of tutoring for legs that lag. I believe that asymmetries are about both cause and individual thresholds; meaning each athlete has unique needs, and the reason for imbalance is a key factor.

Athletes with great global strength and power tend to get away with asymmetries because their nervous system can throttle down force without a problem. Fatigue is usually the culprit behind many non-contact injuries, as exhaustion stems from chronic and acute loading mistakes.

Two studies that cross my mind with split squats and asymmetries are the Norwegian study on the stride parameters of sprinters and the Lockie study on acceleration and split squat asymmetry. Those two studies are good at asking better questions, but they don’t really nail the coffin shut on what is happening with the nervous system and asymmetries.

If asymmetry is great, why not just train one side of the body and see what happens? Of course, nobody in their right mind would advocate for that and it almost sounds silly, but we need to swim through the grey area better. Keeping a 5-10% difference in leg strength makes sense, but chasing purity might just frustrate the coach and spook the athlete.

Load distribution means the amount of contribution from the rear leg compared to the front leg, and the challenge is to ensure that as the load increases, the ratio of contribution stays the same or the absolute contribution remains the same. There is a big challenge in determining how much the upper body contributes to hand-supported split squat options, but my suspicion is that balance helps more than anything with this style.

Loading is about maintaining the same center of pressure (CoP), as it’s important that the load recruits the neuromuscular system the same way for comparison reasons. It’s fine to change up the pattern of pressure, but only if it’s intentional and meaningful. Shifts in lean, changes in split stance, and even the height of the bench or stand can all induce a change that must be accounted for.

I prefer 10-20% of rear leg support contribution, but keep in mind the split stance will recruit the deep stabilizers differently than bilateral lifts. We don’t yet know how much this matters, but let’s not attack coaches who have athletes squat twice bodyweight when your own athletes are split squatting with similar loads in a foreign stance.

Add Isometric Holds to Potentiate Through Plateaus

I wrote about potentiation twice, and if I had to write my favorite isometric exercises article again, I would include the isometric split squat. Due to the stability factor, it makes sense to use low boxes or implement submaximal iso-eccentric overload with Bulgarian split squats. The simple addition of an accommodating resistance band overloads the movement at the top, thus creating a greater isometric challenge. Just one set of holds, whether on the top part of the lift for five seconds or the deep part of the lift for 10 seconds, is enough to raise the quality of work after the warm-up.

Isometric contractions against a static bar are useful because they allow the front leg to really get honest effort from the removal of a cheating rear leg. We don’t use this when we train, due to the inconvenience of changing the rack back to normal weight-training configuration, so this is sometimes performed in a low isometric squat rack or with overloaded jerk block stations. I have seen a few custom split squat bars designed to mimic the benefits of the hexagonal bar, but they have yet to excite me as isometric enhancement options.

Video 3. A few reps are all it takes to potentiate the legs, and I find isometrics useful because they decrease the total eccentric load of the workout. More high-quality work with lower soreness post session is a great workaround concept during long seasons. The resistance here is for demonstration purposes, so you will want to load the bar higher to near 1 rep maximum at peak height.

One word of caution: Plateaus in training are not always a bad thing, and sometimes plateaus are just overreaching that needs rest rather than overload. If an athlete’s strength levels fluctuate up and down and progress is unsteady, it’s better to reduce both volume and intensity for a phase and then go back to isometric potentiation methods. In order to reduce improper use of potentiation, I like using these exercises when athletes want to break plateaus that occur from conservative loading patterns.

Build an Eccentric Reserve in the Split Squat Position

It’s a good idea to use flywheels, bionic resistance, and even conventional weight training with split squat training. I am not a fan of eccentric training with split squat landings from high boxes simply because the rear foot toe tends to take a beating. Sometimes I have to be careful with in-place split jumps (more later), so altitude landings are just not happening. Here are four workout options with eccentric split squats, specifically the Bulgarian split squat:

Chain Split Squat

The use of chains is popular now with higher rep split squats, and for good reason—chains and bands work. The main issue with chains is that you need a very smart setup because the stroke is not the same and the weight needs to be higher. A combination of barbell load and chain is recommended for this option, and rep ranges should be closer to the 6-8 zone. Resting between sets is necessary for the lower back, since the rep range is higher and the work sets are literally doubled when training two legs. Finally, the use of bands is fine if you have a great rack, but for gyms that don’t provide such a feature, chains will be the choice.

Classic Two Up and One Down

While far from perfect, the two legs up and one leg down method of eccentric training is great for many exercises, not just split squats. I don’t think the split squat is an ideal candidate for bilateral concentric and unilateral eccentric approaches, but it’s good enough when high rep partials are used. If you apply this technique, you bilaterally quarter squat one rep up and split squat one rep down for a long contraction of nearly 5-10 seconds.

With one or two sets performed in a workout, it’s a big shock to the body. Dual elevation in a good squat rack is likely necessary for both safety and practical reasons. I have used this method a few times, but found it too cumbersome unless assisted bands are used.

Depletion Flywheel Split Squat

Instead of going down slow with an overload, go fast and use high rep ranges with a flywheel split squat. I am not a fan of high repetition ranges, but this is the rare exception because athletes can do them fast and safely when biofeedback is live and in real time. I don’t recommend doing any depletion work with flywheels, unless you have a kMeter or another sensor. Using biofeedback live enables coaches to cut the set at the right time based on the eccentric capacity changing from fatigue.

Velocity-Based Bulgarian Split Squat

While technically not an eccentric overload, the use of VBT is a good idea to determine when eccentric turnover slows down. You can compare during the set with every rep, or compare set to set if you are doing true singles. The goal is to look at the peak speeds and see if the drop demonstrates real fatigue. I have seen cluster sets make a big difference when athletes need to get quality training done, but I have also seen classic straight sets work like a charm. VBT is great for speed down and speed up, as well as range of motion in the exercise.

Video 4. From single rep testing to higher rep monitoring, using an LPT such as GymAware makes sense. Barbell stroke and peak velocity with moderate loads are useful when ensuring athletes don’t grind too much.

Eccentric Bulgarian split squats are not a wise staple all the time, as all eccentric work is taxing and should be used sparingly. Also, with eccentric work it’s important to know how regular conventional training overloads the body, as awareness helps to prevent unnecessary soreness and fatigue.

Use Split Jumps When Performing French Contrast Training

Split jumps are not a very common exercise, but I would argue that they are more valuable than box jumps any day. Jumping on a box is perhaps the most overrated exercise, as they don’t help with landing—they just fool the athlete into believing they are doing more than they really are. If I were to use a soft landing, I would perform Cherbakis, where the athlete drops down between boxes and jumps up and lands in a split position. At least the first landing is reactive and the bracing at the end is more athletic.

Split jumps aren’t a very common exercise, but they are more valuable than box jumps any day, says @spikesonly. Share on XVideo 5. Long response split jumps are great for teaching and athletes who want to feel rhythmic after going heavy can do them. Dr. DeWeese coaches his athletes to use a rotating arm swing, which is a great way to connect the body.

I reviewed my favorite jump movements in the top plyometrics exercises article, and I love in-place jumps due to the high quality of their technique, which reduces the horizontal technical demand. It is great to do split jumps as either same leg stance to same leg stance or alternating because it cements in technique by purposely being redundant. After the athlete is polished, challenging them with variation is a welcome progression, but it’s better to do it right early then get too cute by adding in “chaos” or inappropriate variations. While I appreciate the science of motor learning and dynamic systems theory, bad technique is bad technique, so don’t let open research ideas push away classic training principles.

Generally, the split jumps have four styles or options, and I don’t like elevated split jumps and barbell loaded work that incorporates a lunging pattern. The primary split jumps are those done in place and you should switch with stiffness (short depth) or use the range of motion to get power. Whether an athlete keeps the same leg in front or alternates doesn’t really matter, as long as they maintain technique.

Sometimes you need to deplete the body safely for it to adapt, and pairing with Bulgarians first in isometric form or with traditional approaches is a great option. There is emerging research on French Contrast methods now, and pairing split jumps with Bulgarian split squats is one possible combination that coaches can use.

Fine-Tune Bulgarian Split Squats with Your Athletes

As with any movement, it’s better to do it right and load later than to get into a bad technique crossroads when the weight becomes a problem. No exercise is perfect for everyone, and sometimes you need to cast aside a favorite weight room movement to make way for a better alternative. The split squat, elevated or not, is a great option but not a necessity.

If you want to get the most out of an athlete, you need to get the most out of an exercise, says @spikesonly. Share on XIf you want to get the most out of an athlete, you need to get the most out of an exercise. Following just one of the recommendations is enough to see and feel the difference with Bulgarian split squats, and even applying the suggestions to other exercises will reap big benefits down the road.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]