My phone had overheated, so I could no longer check, but by all accounts, it was just over 110 degrees in Lancaster, California, as—for the second time in three years—I was beginning the home plate meeting of a USA Softball tournament championship with an apology.

“I’m sorry—we’re done. We can’t give you anything close to a real game.”

The opposing coach shook my hand and nodded—he already knew. Coming out of the winner’s bracket, his team from San Juan Capistrano had reached our late Sunday final by winning a single morning semifinal. Meanwhile, after staying alive with a win well after 10 p.m. Saturday night, we’d climbed out of the loser’s side of a double-elimination bracket on Sunday with grueling back-to-back-to-back-to-back wins, starting at the crack of the dawn and battling onward through the day’s escalating heat.

An hour northeast of Los Angeles, on the western edge of the Mojave, Lancaster is mostly known for hosting sports tournaments and having a stretch of road that vibrates the Lone Ranger theme if you drive your lane at a designated speed. Across the city’s sprawl of field complexes and city parks, the desert wind blasts bullying waves of dinge and tastes like freeway exhaust and fryer oil. As the Capo Beach girls warmed up with pop flies and pump-it-up music, my middle-schoolers zoned out around misters in our dugout, trading cooling towels and ice cream dreams.

The plate ump, Joe, winked and said he would put the game on a clock—he came from a family of umpires and liked to joke with the players about how he could still show the correct ball and strike count despite missing fingers on one hand. Instead of the seven-inning final dictated in the USA Softball rules for the B-State Championship, we’d just play for an hour and 20 minutes or until a mercy rule kicked in, whichever came first.

The Unnameable: Where Poetry Meets Performance

“You must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.” – Samuel Beckett

In the world of sport, one of the most galvanizing moments is the injured or exhausted athlete rising off the track to limp, hobble, or even crawl across the finish line. The time is no longer of any consequence; the pure act of finishing the race is a triumph of the human spirit. Stay down or get up, that you-can-do-it inspiration quickens and swells an innate rooting response among spectators whose daily lives turn on small and large iterations of that exact decision.

I can’t go on…I’ll go on.

Touching a similar nerve, speed coach Derek Hansen recently sparked a discussion by posting a quote from poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht:

“Great sport begins at a point where it has ceased to be healthy.”

Context matters, and there’s a lot to unpack with Brecht—inspired by boxing, the German author sought ways to use the visceral spectacle of the ring as a vehicle to revolutionize a stagnant theater scene, wanting to recreate the same stripped-down and primal connection between fighters and a crowd on stage between actors and their audience (and, beyond that, to illuminate ways that sport and art could revolutionize the proletariat against a corrupt and decadent bourgeois class sliding toward fascism in pre-Hitler Weimer Germany).

But just as the boxers in Brecht’s work grappled with turning points where their raw gladiator’s instinct and will to stand triumphant demanded a sacrifice to their own health,1 storied moments of “great sport” frequently follow the same narrative, whether Christian Pulisic throwing himself into a collision to score a crucial World Cup goal or Pat Mahomes having his ankle folded sideways between two linemen and staying on the field to captain the Chiefs to a playoff win.

Those moments of bravery or will—daring any physical costs to win or to endure—are not foundations to build our youth sports models around, says @CoachsVision. Share on XThese moments of bravery or will—daring any physical costs to win or to endure—are not, however, foundations to build our youth sports models around. With young athletes, progress is the purpose—to play your next game even better than you did the game before. When my teen athletes want to grit their teeth and grind through common injuries, exhaustion, or illnesses, I always repeat one of Tony Holler’s core tenets: never let today ruin tomorrow.

On a larger scale, however, with youth soccer, softball, baseball, basketball, volleyball—you name the sport—the ability to survive the schedule plays an increasingly large role in success, whether managing the accumulation of games across a calendar year or the number of games stacked over a single day/weekend in a tournament or showcase. Attrition has become a defining feature of the model and one of the most substantial obstacles to long-term player development, with players derailed from reaching their athletic potential due to injuries, burnout, or overwhelming costs (dollars, time, sacrifice of other interests, etc.).

Those indelible images of runners crawling across the finish line? It goes without saying that those are not the winners of those races—the ability to endure and the ability to excel are not one and the same. That statement reads so black and white that you could print it on stickers and T-shirts, but it’s never so straightforward. There is the game…and there is the marathon. Both press on, simultaneously, in and out of sync, intertwining, merging, amplifying, severing, and—at times—veering into a direct, sabotaging conflict.

How Many Games Do Young Players Play?

In San Diego—where I coach eighth and ninth graders on multisport-based club soccer and travel softball teams—the weather allows outdoor sports to be played year-round. Driven single-sport athletes can compete in those sports 52 weeks a year, filling any breaks for their school or club team by playing games with other team(s) in that sport; multisport athletes, meanwhile, juggle the same superimposed, year-round schedules, just as a more complex factor multiplication problem.

This past year, one of our opponents on the 14U travel softball circuit played 154 games from August 2022 to August 2023—or very nearly the number of regular season games of an MLB team. This was spread out over a year rather than a seven-month pro season, and a number of those 154 games were informal “friendlies”… but still, there are not many who would argue that the purpose of a 162-game MLB schedule is for the players to get progressively better as a result of that dense accumulation of game play and therefore perform at a definably higher level on game #150 than they did at game #50. The length of the MLB season is what it is because it maximizes annual revenue within what’s been settled upon as an acceptable threshold of performance decrement and injury risk.

Should I repeat that? A professional season in any sport is the length that it is because it maximizes annual revenue within an acceptable threshold of performance decrement and injury risk.

Even at the professional levels, that “threshold” is the subject of heated debate, whether by coaching staffs addressing the demands on a Premier League star also juggling Champions League games and national team duties or in collective bargaining discussions on the length of an NBA or NFL season (and accompanying pre- and post-seasons).

What is an acceptable threshold of performance decrement and injury risk for developing teen athletes?, asks @CoachsVision. Share on XFor developing teen athletes, though, what is an acceptable threshold of performance decrement and injury risk? That question comes into starker relief once you remove the counterweight and operate on the assumption that annual revenues do not, in fact, need to be maximized for this population. These are, after all, the athletes we should be investing in and not relying on as income drivers.

Finding the right answers relies on asking the right questions, and for individual youth players, the question of how many games are too many games is broadly unanswerable and falls into the dreaded it depends zone because of the extreme variability in:

- Roster sizes

- Positions and roles

- Playing time

- Competitive level and playing intensity

- Game length and game rules

- Travel/academic demands

One-hundred fifty softball games for a 14U team with 22 players on the roster, including five pitchers and four catchers, is an entirely different thing than 150 softball games for a 14U team with 13 players, including three pitchers and two catchers. That 15-year-old ECNL soccer player from figure 2? She could be on a club team of 22 girls and a high school team of 26 and therefore accumulate significantly fewer game minutes across 60 games than another 15-year-old who plays 50 games on small roster teams where she’s grinding out 75–80 minutes every game.

That’s all before you consider the heap of non-game stressors. Do they practice two days a week or four? Are their practices nearby after school, or do they need to commute an hour through evening traffic just to get to a session that ends under nighttime lights? Are games local? Regional? National? Are they traveling out of state to compete in weekend-long, pressure-packed ID camps? Are they also doing strength or speed training? Do they play another sport? Are they taking AP/Honors classes with a high-stress academic load?

To paraphrase Indiana Jones…It’s not the games; it’s the mileage.

Rather than how many games are too many games, a more specific question for coaches, parents, and players is: How much fatigue is too much fatigue?, says @CoachsVision. Share on XAt a more individualized level, then, rather than how many games are too many games, a more specific question for coaches, parents, and players is: How much fatigue is too much fatigue?

Kids These Days

“Unpopular volleyball training tip of the week—coaches and parents, let your volleyball player take time off. They compete, they train, they practice, they do private lessons year-round. For our club, we stop structured training Tuesday night because of Thanksgiving Break, and then our athletes are off through Sunday. That’s a perfect opportunity to let their bodies rest and recover.”

Coach Missy Mitchell-McBeth shared these thoughts in a video on social media shortly before Thanksgiving, compelled to frame the notion of spending a few days off to rest/recover with family on a national holiday as an unpopular, out-of-step opinion.

And it is.

This holiday stretch is useful to narrow in on as it represents an annual collision of game and marathon, of today and tomorrow. With pesky inconveniences like school and work out of the way, the weekends bracketing Thanksgiving are marketed as a grind time where “the real” separate from the slacker pack. Showcases, specialty skills camps, college ID camps, tournaments, sunrise trainings: It’s on—are you willing to do what it takes to make it to the next level?

Except…all those things have already been on: as Coach Mitchell-McBeth points out, competitive student-athletes will have been competing, practicing, training, and doing private lessons without a break since at least Labor Day, though more likely from some point earlier in the summer.

If you won’t take time off for a national holiday, when will you?

Ten years ago, during this November holiday stretch, I interviewed Jay DeMayo (CVASPS) about managing fatigue with Richmond basketball:

“An important thing I’ve learned is to give them as much as they need, not as much as they can handle. When it comes to exercise or training, it’s not a matter of ‘what can these kids push through.’ Eventually you’re going to run out of wood to pound the nail into. It’s a matter of ‘what’s the dosage you need to give them for them to improve.’ And after you get to that, then why do you need to go further? Why do you need to tap into reserves that don’t need to be tapped into?”

Image 1. A few days before Coach Mitchell-McBeth’s Twitter missive, I posted a “Happy Thanksgiving” note to the multi-sport players on my softball team, encouraging them to relax and enjoy 10 days off for the holiday after competing hard across multiple sports for the previous four months.

It’s never completely black and white—should those reserves be tapped into? For uncommitted high school upperclassmen in a prime recruiting window for their sport, there are tournaments/showcases/camps during this time that provide legit and timely access to coaches from colleges they want to play for. In this case, digging in and tapping into those reserves today can help create a desired tomorrow.

For most, however, Thanksgiving showcases, camps, tournaments, and sunrise trainings are indistinguishable from those available the other 51 weeks of the year across what author Christine Yu refers to as the “$19 billion youth sports industrial complex”2 in her book Up to Speed, writing in the chapter “The Phenom Years”:

“With little advice to guide girls through this stage of life, athletes, parents, and coaches are left to fumble through the dark in a way that may compromise a young person’s long-term physical, mental, and emotional health, not to mention their love of sports.”

Like most team sport coaches, I’ve been on both sides of the equation, with teams that peaked at just the right time and teams that barely managed to crawl across the finish line…and the vexing part is the model/planning/philosophy was largely the same.

So, how much fatigue is too much? Start with conditions that prevent athletes from taking time off:

Factor #1: FOMO Knows No Fatigue

Even when the marathon has ground down their bodies and passion for the game, competitive kids and parents still retain a powerful compulsion not to be the ones stuck without a chair when the music stops.

Two days after Thanksgiving, Jacob Whitehead and Liam Tharme published an article in The Athletic diving deep into how the obsessive *Mamba Mentality* stimulates and impacts reward centers in the brain: “An Addictive Personality Can Facilitate Sporting Greatness—But What Are the Consequences?”

“The path to mastery is steep, alluring and slippery,” sports psychologist Jeremy Snape told Whitehead and Tharme. “For elite performers, the same obsessive drive for continual improvement and gratification can spill over.”3

Standards are set by that obsessive more more more mindset and a valorization of the grind. For athletes growing up online, they scroll TikTok and Snapchat and Instagram weekend after weekend and see posed, filtered, and geolocated highlights of their peers traveling further and further and playing more and more games. The urge not to be outdone is deeply entangled with their identities as athletes.

Hence: Unpopular volleyball training tip of the week—let your volleyball player take time off. Time off is unpopular. It’s a hard sell.

Antidotes:

- Hype your recovery. Brand it. High school football coaches succeeding in Feed the Cats-inspired “sprint-based” football programs know they’re rebelling against a massive body of tradition. They’re conspicuously not positioning themselves as “readiness-based football” or “recovery-based football”—Brad Dixon’s pillars, relentless, rest, repeat can win a FOMO battle with embrace the suck by selling rest as that key bit sandwiched between relentless and repeat.

- Out-do game play with your recovery activities. In the heat of the past two summer tournament seasons, we’ve taken my soccer team off the field for weekend excursions to a popular recreational lake and an axe-throwing facility. Last October, my softball players were dragging, so we passed on entering a Halloween tournament and sent them on a team outing to The Haunted Trail instead. Whatever your players like doing as much as they like competing, substitute that in place of games in the name of recovery and team bonding.

Factor #2: Coaches Know Tomorrow May Never Come

From the pros to college to high school to youth levels, player movement has become a defining feature of sport—holding a team together is now one of the hardest tasks for a youth coach. And not just year-to-year, but month-to-month.

Holding a team together is now one of the hardest tasks for a youth coach. And not just year-to-year, but month-to-month, says @CoachsVision. Share on XBecause of factor #1, club coaches know that if they don’t keep their players constantly playing, their most ambitious athletes—those who drive the game—will soon jump to a team that does. And high school coaches needing to rival pay-to-play versions of their sport often only have a compressed 10–12-week season to do so, which means pumping up and maxing out a game schedule. Coaches then zero their sights exclusively on the game in front of them—if they start zooming out on the marathon, the athletes are gone.

Antidotes:

- Bridge club and high school schedules. Players 24 hours from completing a 20+ game fall club soccer season will take the field for volume-accumulation practices and winter pre-season games with their high school teams. For the athletes, this is not by any definition the *start* of a season, but simply a non-stop continuation—and the same for club coaches getting those players back in the spring just days removed from their winter high school playoffs. In these transitional phases, training and games need to make sense in the context of mid-season play—activities modeled on a traditional pre-season ramp-up phase should be evaluated and trimmed accordingly.

- Break for holidays. Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter, and the 4th of July offer five natural weeks of recovery time in a playing year. Plan a couple more two-week off-stretches, assume each player will take at least a week off on a family vacation, anticipate rain/inclement weather for a week or two, and now, even without a formal off-season, you’ve reduced the yearly game load. On the coaching side, by this point I’ve heard almost every concern and complaint under the sun—how come we’re not playing on New Year’s Day? is not one of them.

Factor #3: Problems? The Parking Lot Doesn’t Care.

Sore ankles and knees? Sleep-deprived? Burned out? Limping through games on top of games? The parking lot charging each car through the gates $15 doesn’t care. The venue charging a $12 entrance fee to watch your kids on the court doesn’t care. The tournament organization charging each team a $1,200 registration fee doesn’t care, and the roster management service tacking a 5% surcharge onto that $1,200 tournament entry doesn’t care either.

The youth sports industrial complex has determined that the acceptable threshold of performance decrement and injury risk is any. Or, to be more accurate, that threshold never factors into calculations in the first place. If you follow the money in professional sports, at some point, you’ll land at an ownership group that ultimately has some stake in how well their players can perform, particularly later in a season. If you follow the money in youth sports, you run aground at an archipelago of loosely connected enterprises that share a common formula: more games = more revenue. Period.

Antidote:

- Be willing to play outside the system. This concept can come into conflict with the above point about cutting out superfluous pre-season games, but the ability to plan and execute games where the only end value is to the players—not parents wanting spectacle, not the youth sports industrial complex—can balance an athlete development program with games in service of the marathon. If great sport begins at a point where it has ceased to be healthy… there can be something healthy and sustainable about games that do not aspire to be great sport but serve the sole purpose of maturing the investment in your players over the long run.

Déjà Vu All Over Again

The first time I began the home plate meeting of a USA Softball tournament championship with an apology, the tone and terms were different.

“I’m sorry—we’re done. I don’t think we can give you anything close to a real game.”

“I don’t even know if playing this game is the right thing to do,” the other coach conceded, as we both acknowledged that who would win was not, at this point, in question.

They were entering just their second game of the day, the first of which they’d breezed through in a three-inning, 15-2 mercy rule win. Meanwhile, to reach the late afternoon final, my team had climbed out of the loser’s bracket, winning back-to-back-to-back-to-back games spanning 26 innings and 10 consecutive hours camped out in the same dugout.

Is playing this game the right thing to do? It’s always a judgment call—coaches make one after another, small and large. How much fatigue is too much fatigue?

Look. Listen.

Girls in the dugout singing songs and playing hand-clapping games. Kids who hadn’t pitched or caught all weekend excited for their chance to finally pitch and catch, and in a championship game, no less. Ice cream dreams made real; all team rules thrown out the window with frozen treats brought over from the snack shack. Tomorrow? Nothing to do but sleep in and go to the beach. “Great sport” may begin where it ceases to be healthy, but willfully subpar sport can begin and end in completely different places.

Why do you need to tap into reserves that don’t need to be tapped into?

Before answering that question, you have to ask where did those *reserves* come from in the first place? You can’t bank what you’ve never had. Earning those reserves takes a process of stress, recovery, and adaptation—while never letting today ruin tomorrow, Tony Holler pushes his 400m sprinters through purposeful, demanding lactate workouts intended to build those reserves for a future race.

“These workouts, like the 400, require a leap of faith. Acidosis creates a discomfort most athletes have never truly experienced. To call the pain intense would be like calling fire hot. The good news: the pain is temporary, the body will adapt quickly to become biochemically tougher, and we don’t have practice tomorrow!”

When kids are surveyed about what they enjoy most about youth sports, the feelings of confidence and pride from doing something challenging and the feeling of getting better at something with their teammates typically rank higher than immediate gratifications like winning or flashy team gear. Those impacts can translate more deeply—a recent study by Emily Nothnagle and Chris Knoester posed questions about perseverance, resilience, and work ethic as they relate to the quality of “grit,” with the researchers finding:

“The demonstration of more grit among respondents who participated in sport continually, after accounting for their perceptions of their athletic experiences’ effects on their work ethic, suggests that sport participation affects the development of grit to a greater extent than many people even realize.”4

I can’t go on…I’ll go on.

The downside from that same study? Adults who played youth sports but quit or dropped out actually scored lower in markers for grit than adults who had never participated in sports at all.

Is playing this game the right thing to do?

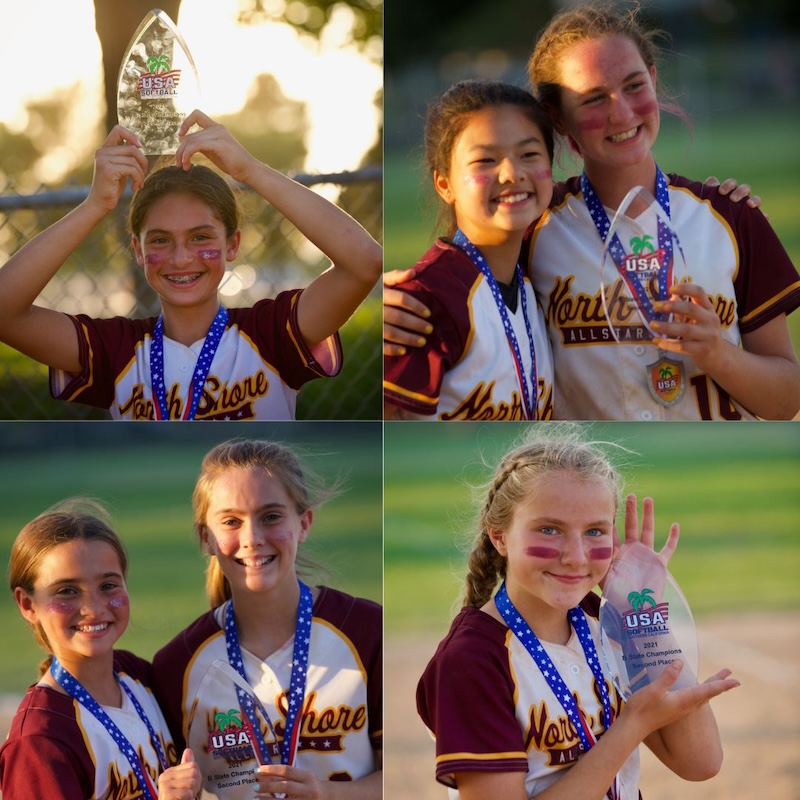

Out in the dust and heat and wind in Lancaster, after conceding to the San Juan Capistrano coach that we couldn’t provide great sport, my players took the field to an extended, touching, and rousing ovation from the boisterous Capo supporters— stay down or get up…you can do it, girls! And the players believed they could—they’d been in the same position before, having won those back-to-back-to-back-to-back games and battled out that fifth and final game of the day two years prior.

The ability to endure and the ability to excel are not one and the same. After the hour-and-20-minute time limit had elapsed, Joe the ump called “ballgame,” with Capo winning 10-5. It was not great sport, nor was it ever intended to be, but the girls closed out the final without giving up or being mercied—as parents from both sides of the stands stood for another rousing ovation, Joe came over to our dugout and presented the girls with the game ball, saying “I never give these away, but you girls are warriors and showed something special out here today.”

The game and the marathon. Across the long haul of a young athlete’s career, they cannot excel without learning to endure, and they cannot endure without being healthy enough to excel. Share on XThe game and the marathon. Across the long haul of a young athlete’s career, they cannot excel without learning to endure, and they cannot endure without being healthy enough to excel. How much fatigue is too much fatigue? Look. Listen. Coaching is one judgment call—one leap of faith—after another.

(Lead Photo by Erica Denhoff/Icon Sportswire)

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Rebeccah Marie Dawson. “SPORT IST DER NERV DER ZEIT”:

THE POLITICS OF SPORT IN GERMAN LITERATURE, 1918-1962.” UNC.edu.

2. Christine Yu. Up to Speed. Riverhead Books. New York, 2023.

3. Jacob Whitehead and Liam Tharme. “An Addictive Personality Can Facilitate Sporting Greatness—But What Are the Consequences?” The Athletic.

4. Emily Nothnagle and Chris Knoester, “Sport Participation and the Development of Grit.” Leisure Sciences. June 2022.