[mashshare]

The following is an excerpt from “Coaching the Horizontal Jumps,” an online educational program dedicated to the long and triple jumps, representing the third course in the ALTIS Track & Field Education Series.This digital course features 12 modules written by esteemed coach and educator Irving “Boo” Schexnayder, and is packed with coaching insights, tips, tools, and progressions crafted to build topic-specific understanding, develop targeted coaching skill sets, and accelerate athlete development.

A seldom voiced but critical question to ask before teaching skills is, “What makes ‘good’ techniques ‘good’?” Obviously, good techniques foster good performances, but it’s complicated. We see athletes succeeding while doing radically different techniques, and the fact that these athletes might vary in their talent levels further confuses the issue. Is the athlete succeeding because of good technique, or in spite of it? We also make the mistake of thinking that elite performers have perfect technique; this often isn’t the case, either.

Below, we explore some principles that should guide every coach’s thought processes before determining exactly which technique or style you want to teach your long and triple jumpers.

1. Commonality-Based Teaching

We can define a commonality in two ways:

- A commonality is a technical feature we see in multiple events.

- A commonality can be a technical feature we see in a single event, executed by many different, successful performers.

In this case, we are more concerned with the second definition. No two performers in an event share identical technical models.

However, when we examine the horizontal jumps (or any event, for that matter), we can find technical features that all successful jumpers share. We should build our technical models around these commonalities, rather than around differences. For example, we saw features like dorsiflexion of the ankle, heel lead, and flat, rolling contacts numerous times in our technical exploration.

2. Technique and Style

If we study the top performers in any event, we see many things they do the same, and we base our technical teaching on these commonalities. But what about the things they do differently? When we see top athletes doing things differently and still performing at high levels, it becomes obvious that these differences must not matter much. We classify these as differences in styles.

Good coaches teach technique and allow style to evolve, says @BooSchex. Share on XFor example, any jump competition shows jumpers using single and double arm styles. If they are all highly successful, it’s fair to ask if the arm style matters that much. Good coaches teach technique and allow style to evolve. This simplifies the teaching of technique tremendously for the coach and athlete. More importantly, the efficiency of the teaching process improves dramatically because of the elimination of unnecessary teaching.

3. Sports Science Contributions to the Technical Model

When building a technical model for an event, we draw upon various fields of sports science for reason, insight, and supporting evidence. These fields of sports science may agree in supporting a particular technique; however, they may also conflict.

For example, we have documents showing that takeoff angles in the horizontal jumps are wildly different than the ideal angles suggested by projectile physics. Here, the sciences of physics and human anatomy conflict. In these types of cases, it is important to identify the conflict and weigh the positives and negatives. You should evaluate techniques in terms of physics, physiology, and anatomy.

At times, even psychological reasons might come into play. Technical styles that are more physically demanding and challenging can sap emotional energy levels and extinguish the passion and love for an event.

4. Evaluation of Technical Model Changes

Why would a coach choose to change an athlete’s technique? There are three potential answers to this valid question:

- Performance Level: Improvements in performance level may result.

- Consistency: Improvements in consistency and frequency of good performances may result. Maybe the athlete might not hit a huge personal best, but the average performance grows closer to that PR level.

- Injury Prevention: Decreased levels of risk associated with the technique may allow for injury-free performances. For example, a triple jumper who reaches on each phase and relies on big swinging movements in compensation can be effective, but this is a risky technique. Switching to a technique based more on speed maintenance would drop this risk quite a bit.

5. Cost/Benefit Analysis

When deciding that a change in technique is needed, the coach should apply a cost/benefit analysis before undertaking the change. These are key questions to consider in that analysis.

Benefit: What will be the type and amount of potential benefit?

Difficulty: How difficult will this change be, and will I have enough time and resources to accomplish it? For example, changing an arm style or switching jumping legs takes quite a bit of time. If you are in a situation with a very short preseason or limited training opportunities, such a change might not be wise.

Further Issues: Is the change likely to result in other problems? For example, an increase in the number of steps used in the approach might increase velocity and potential jump distance. But, if small technical problems at takeoff explode into huge ones as a result of this added speed, things might very well get worse.

Scientific Rationale: Do sports science and commonality study support such a change?

6. Biomechanical Efficiency

It’s good practice to evaluate techniques in terms of biomechanical efficiency. Being biomechanically efficient will always result in good performances and minimal injury risk. We are fortunate that the techniques that produce good, consistent performances are the same ones that minimize injury.

Being biomechanically efficient will always result in good performances and minimal injury risk, says @BooSchex. Share on X7. Radical Techniques

We will always see certain jumpers who show radical aspects of technique. However, the techniques that permit good performances more frequently and minimize injuries will always be conservative, existing in the middle of the technical continuum.

8. Periodization of Technical Training Phases

It’s important to organize technical training with the same degree of detail we use in assembling other aspects of the training program. A good starting place is the identification of the phases of technical training. You can divide technical training into four phases. These phases are described and arranged chronologically in the training program as follows:

- A Phase of Radical Changes

- The first teaching priority should be a phase concentrating on radical technical changes, if any need to be made. Necessary, radical technical changes require time, so they should be the first priority on the training calendar. For example, a jumper who might change the jumping foot, or change from a single to double arm technique, will require significant time to assimilate the new movement patterns, so those changes should be made early. Ideally, this phase should be done prior to the formal start of the training year, possibly during the time of transition from one season to the next.

- A Phase of Technical Exercises and Partial Movements

- Next should come a phase of technical exercises. In this phase, drills and technical exercises may be used, and the event might be broken into parts to facilitate learning. This phase should begin immediately upon the formal start of the training year, but should not extend beyond the midpoint of the general preparation period. This phase might not be necessary for jumpers with high levels of experience and who are reasonably, technically sound.

- A Phase of Whole Movements and Synthesis

- Our next phase should feature technical rehearsal and a progression of intensities to prepare the jumper for meet intensities. This technical rehearsal might not look exactly like the competition at all times, and speeds and intensities are often less than those in competition. Regardless, the coach should strive to focus on whole, complete movements and avoid “breaking the event down.” As this phase progresses, practices resemble competition more and more, as whole movements are emphasized and intensities increase. This phase should begin no later than the midpoint of the general preparation period, and in most cases, end at the start of the competitive season.

- A Phase of Problem-Solving

- The final phase should be a phase of problem-solving, allowing time to correct any problems that may arise during synthesis. Athletes will show small errors even after the soundest technical teaching, so some opportunity to correct errors prior to critical competitions is needed. This phase generally begins at the start of the competitive season and consists of the early-season preparatory competitions.

9. Technical Training Volumes and Density

Density of practice refers to how frequently a skill is practiced. This depends upon many variables, including training age, experience, proficiency, and number of events the athlete trains for. Young athletes should have a higher density of technical sessions in their training.

It’s often a good idea for young athletes to practice their events almost daily, driving interest as well as learning. Older, more experienced athletes may devote only one or two days a week to technical rehearsal. One session per week of approach development/rehearsal and one to two days per week of technical rehearsal (per event) are common with established athletes, but exceptions exist.

10. Session Volumes

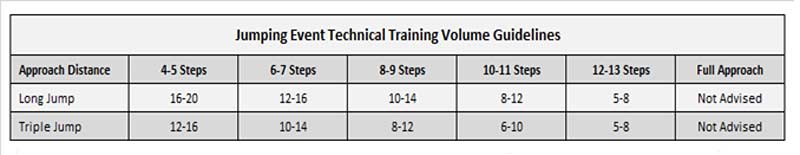

Technical training volumes must be sufficient to allow for opportunities to learn and rehearse skills, yet not so excessive that injury risk increases or training is negatively affected. The chart below provides some rough guidelines for jump volumes in training sessions of varying intensities.

Note that while there might be occasional exceptions, we do not advocate the use of full approach jumps in practice, particularly with higher-level jumpers. It is very difficult to create the arousal needed for effective full approach jumping in the training environment. For this reason, we typically plan so that the first few meets of the year serve as our full approach jumping practices. The presence of emotion and arousal in the meets helps greatly in making these first annual attempts at full approach jumping successful.

11. In-Season Planning

In-season, we usually continue runway practice as usual, but we return to shorter approaches in our short run jumping sessions. We do this for several reasons.

Minimize Injury Risk: The slower speeds produced with shorter approach runs greatly diminish intensity, and thus injury risk.

Facilitate Communication: In most cases, the skill has been adequately taught by this point, and practice sessions center around error correction and the communication and cueing processes between the coach and athlete in competition. Neither of these purposes requires high intensities.

Set Up the Following Year: These lower-intensity practices can serve as a very effective technical training base for the following year. This becomes particularly important when training time early in the training calendar is severely limited.

Eliminate Motor Interference: Once in-season, the jumper must be allowed to become comfortable at meet speeds and discover effective runway rhythms. Practice runs that are close to, but not exactly, the same length as the competition length approach show very subtle rhythmic differences and might interfere with the athlete becoming comfortable at meet speeds. Choosing slower runs enables the athlete to interpret practice and meet speeds as two separate rhythms, and the gap between them eliminates this interference.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]