After growing up in the United Kingdom—and having now lived in the United States for the past three years—I’ve found stark differences in the US and UK cross-country training systems. These distinct systems, as well as some historical success stories of certain athletes, have led to very different approaches to training. I will describe the strengths and weaknesses of each system and suggest how we might attempt to offset the latter. These are generalizations; clearly there are exceptions in each system.

US High School System

Younger athletes in the United States are predominantly developed through the high school system with each school having its own team and coach. This leads to frequent, usually daily, contact between coach and athlete. As such, most athletes train daily and often twice a day. Cross-country has a distinct season August-November, and then there’s a break until track season February-April.

Because cross-country has such a distinct season with daily contact between coach and athlete, an emphasis on higher volume programs—more long runs and recovery runs—has developed. This training of the aerobic system leads to better results during the cross-country season. The investment in volume also lays a great foundation for the athlete’s long-term development.

In recent years, the US has seen a lot of success on a global scale across a wide variety of the endurance disciplines. I think the major change in these fortunes comes from the shift away from intensive training to an aerobic emphasis. This seems obvious, as the aerobic system is the dominant energy system for any event 800m or over.

With all the success that these senior athletes have had, however, there is a trend of imitating the high volume approach with high school athletes, to the detriment of their speed and movement mechanics. Some young athletes are given too much volume before their bodies are fully developed to handle these loads. Many athletes get stuck in a movement stereotype more akin to an “old man shuffle.” Negative shin angles, a lack of hip extension, and heel striking way in front of the center of mass even at high speeds are common in athletes in these programs.

Speed work is an afterthought in US cross-country to the detriment of athlete development, says @RickySoos. Share on XSpeed work is often an afterthought, typically consisting of some strides after a 50-minute run when the athletes are exhausted. Some would argue that the ability to run fast when fatigued is important for endurance athletes, and I completely agree. However, there should be a progression leading to this point. How can they run fast under fatigue if they haven’t been taught to run fast when fresh? Check out the ALTIS Essentials Course for more information about key teaching points including programming and progressions.

Also, moving at these slower speeds uses very little of the available joint ranges. This is compounded by the linear nature of running. As more of this movement variability is lost, the probability of overuse injuries increases.

How to Improve Speed Development and Movement Mechanics

Using different terrains can vary the movements and create more resilient athletes in the long term. Uneven footing, hills, and twists and turns will help athletes become more adaptable and comfortable in a larger range of positions.

A multi-sports approach is another great way to keep balance within an athlete’s skill sets. The chaotic nature of team sports develops acceleration, agility, and power, while teaching lateral and backward movements. Loading bones, muscles, and joint systems in a variety of planes and ranges is essential for their long-term health.

One very effective way to offset repetitive running volume is to perform warm-up drills and light circuits after longer runs. These allow the joints and soft tissues to reset to normal ranges before athletes go and sit in class or on the couch for 2-3 hours.

The UK and European Club System

In the United Kingdom and Europe, track and field (or athletics) is run through a club system and almost exclusively with voluntary coaches. Athletes usually train at these clubs on Tuesday and Thursday evenings and then race or train again on Saturday or Sunday. Athletics is more of a year-round endeavor as cross-country runs October-March and track season April-September.

The relative lack of contact between coach and athlete means the training at each of the sessions is much more intense. If an athlete is only training 2-3 times a week, an easy 30-minute run is not the most effective use of time. Athletes are also unlikely to run outside of club training times because running just isn’t cool. At a time when they’re desperate to conform, most athletes would not risk being seen by school friends.

This dynamic means that even during the winter, the slowest pace athletes will run is near anaerobic threshold. Most of the training is track, grass, and hill workouts with races frequently on weekends. This develops the aerobic power and glycolytic areas of the energy system continuum, but there is very little true aerobic development. It’s a shortcut to success as these energy systems can be affected very quickly but at the cost of the aerobic system. Without aerobic development, an athlete will never reach their full potential.

Without #AerobicDevelopment in the UK, runners will never reach their full potential, says @RickySoos. Share on XThe upside of this style is that speed, power, and mechanics are developed much more quickly. The increased rest between workouts coupled with their intensity mean that they are naturally performed faster. So whether implicitly taught or not, mechanics have a better chance of being closer to the technical model. And since the central nervous system is well-rested, more force is produced and over time athletes develop specific strength for their sport.

Issues can occur, though, when they transition to a senior program. Contrary to their US counterparts, UK athletes become stuck in a pattern of always running fast and bouncy, biased toward 2-3 intense track workouts each week. This may have been possible when younger and weaker, but as they grow and get stronger the stresses on the body will become too great with this density of work.

The propensity toward high-force output creates a high amount of tendon stiffness. While great for running economy, if tendon stiffness isn’t offset, the muscle eventually will pay the price for its lack of compliance in the system. Slower running can protect against injuries related to tendon stiffness—assuming that the new volume is introduced incrementally at a slow enough pace.

Indeed, one of the main issues with increasing volumes is that these athletes continue to run too fast with heart rates averaging in the mid-150s on what should be recovery or easy runs.

How to Improve Aerobic Development

It’s essential to educate athletes that, for later development, not everything has to be “eyeballs out” to be beneficial and that rest and recovery don’t have to mean they should do nothing. GPS watches and heart rate monitors are one way to ensure they run at the correct pace, but it’s preferable that they learn to listen to their body.

Having a full conversation during an easy run is a good rule of thumb here. If an athlete has to pause between each sentence, then the pace is likely a little too fast. Low impact cross-training is a great way to stimulate the aerobic system without increasing impact. Check out ALTIS 360 for a free, how-to guide for monitoring cross-training.

Examples of US and UK Training Programs

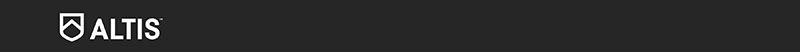

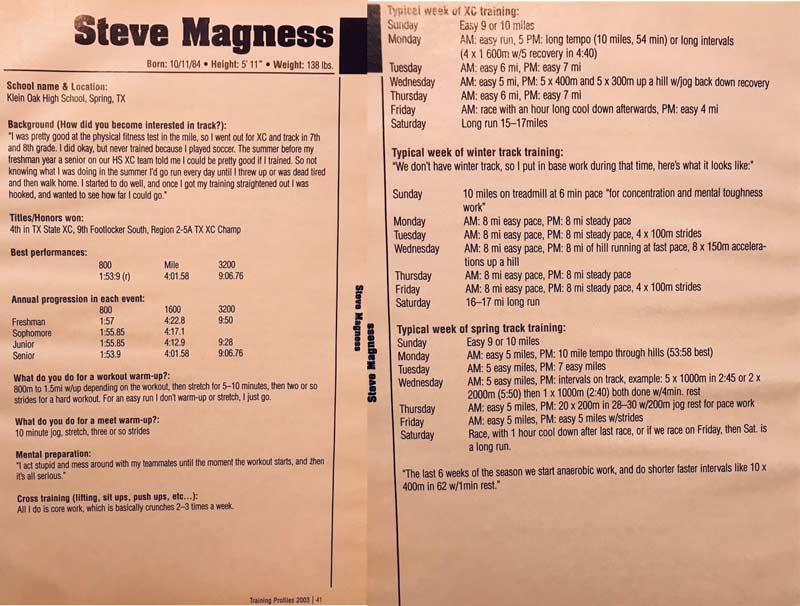

As examples, here are overviews of my training and that of Steve Magness in our final year of high school, when we were around 18 years old. I use these examples because Steve and I ran very similar times in the mile (metric mile for me) under programs that could not be any more different.

Ricky Soos: Typical Week of Cross-Country Training in the UK (September-December)

- Sunday: 1.5 miles WU, 6 miles hilly tempo, short hill sprints, 5-6×30-45s (varied rest); hilly loops were usually very muddy in a wooded area

- Monday: Off

- Tuesday: 2-3 miles WU, Paarlauf relay, rotating through 10×400, 12×300, 20×200; 7-lap time trial on the 4thweek

- Wednesday: Off

- Thursday: 3 miles progression run/tempo

- Friday: Off

- Saturday: Race or off, most weeks would be cross-country race or road relays of 3-7 km

Ricky Soos: Typical Week Of Late Winter and Spring Cross-Country Training in the UK (January-April)

- Sunday: 1.5 miles WU, 6 miles hilly tempo, short hill sprints, 5-6x 30-45s (varied rest); hilly loops were usually very muddy in a woodedarea

- Monday: Off

- Tuesday: 2-3 miles WU, track session—12×200-200, -400, -600, -600, -400, -200, for example; 2x1000m (10 mins); 3-lap time trial every 4thweek

- Wednesday: Off

- Thursday: 3-mile progression run/tempo or more track after cross-country season ended—6×300 (100m jog/walk), for example

- Friday: Off

- Saturday: Race or off

Ricky Soos: Typical Week of Summer Track Training in the UK (April-August)

- Sunday: Race or easy-medium run—3-6 miles

- Monday: Off

- Tuesday: 2-3 miles WU: 2×600 (10 mins), 3×400 (10 mins), 4×300 (8 mins), 6×200 (60s)

- Wednesday: Off or race 2-3 times per season

- Thursday: Track session, for “flow”—2x10x100 (100m jog), 2x12x150 (50m walk)

- Friday: Off

- Saturday: Race or off

Interestingly, neither Steve nor I progressed past this distance during the rest of our careers. Although these are extreme versions of the two systems, they give a good representation of the general themes. It’s interesting to note that Steve’s 800m and my 3000m didn’t progress much, which are clear signs that both programs lacked balance.

Conclusions

On the surface, this discussion may look like the age-old argument of volume versus intensity, which is not incorrect. It goes deeper than that, though. The example training programs show clearly that young athletes are clean slates who will respond strongly to a vast range of stimuli. Just because they produce results and athletes are not ill or injured doesn’t mean they are in the ideal program or system.

During their developmental stage, young athletes are literally shaping their future. The training they follow in these formative years will establish their movement signature, for better or worse. As importantly, though, this earliest exposure to the sport will likely bias them toward that training style for the rest of their careers. These beliefs can take deeps roots and become very difficult to overcome before they do irreversible damage.

Coaches working with youth runners should strive to create malleable, all-around athletes, says @RickySoos. Share on XWithout a variety of different training stimuli, injury and overtraining will become more and more likely. Anyone working with these populations should strive to achieve not only short-term success but also to create malleable, all-around athletes.

Coaching speed and endurance concurrently with general abilities such as strength, coordination, and agility will allow athletes to explore which event and training system is their best fit once they are fully developed.

For more coach and athlete resources from ALTIS, see ALTIS 360.

6 comments

Andy

Any chance of reposting this as it seems to be missing

Christopher Glaeser

Thanks, Andy. The article is now visible.

Hamish Willis

Can’t find the article

Christopher Glaeser

The article is now visible.

Chris Schrader

Very insightful article. Specifically, I appreciate the mention of proper foot landing. I think teaching this at low volumes and paces in the beginning of the summer(TEXAS) can have lasting positive effects if the coach continues to emphasize proper placement of the foot on the grass.

Patrick Hennes

Ricky–excellent post! Truly appreciate the insights. As a U.S. born, bred & based distance coach I have certainly tended to neglect running/sprint mechanics in my career (both as an athlete and as a coach). We are currently working to correct this in our program by dedicating two days/week (45 min. each) of our summer training to developing running/sprint mechanics under the instruction of our school S & C coach. Not only does it seem to be helping with form, etc., it is a literal nice change of pace for our athletes.