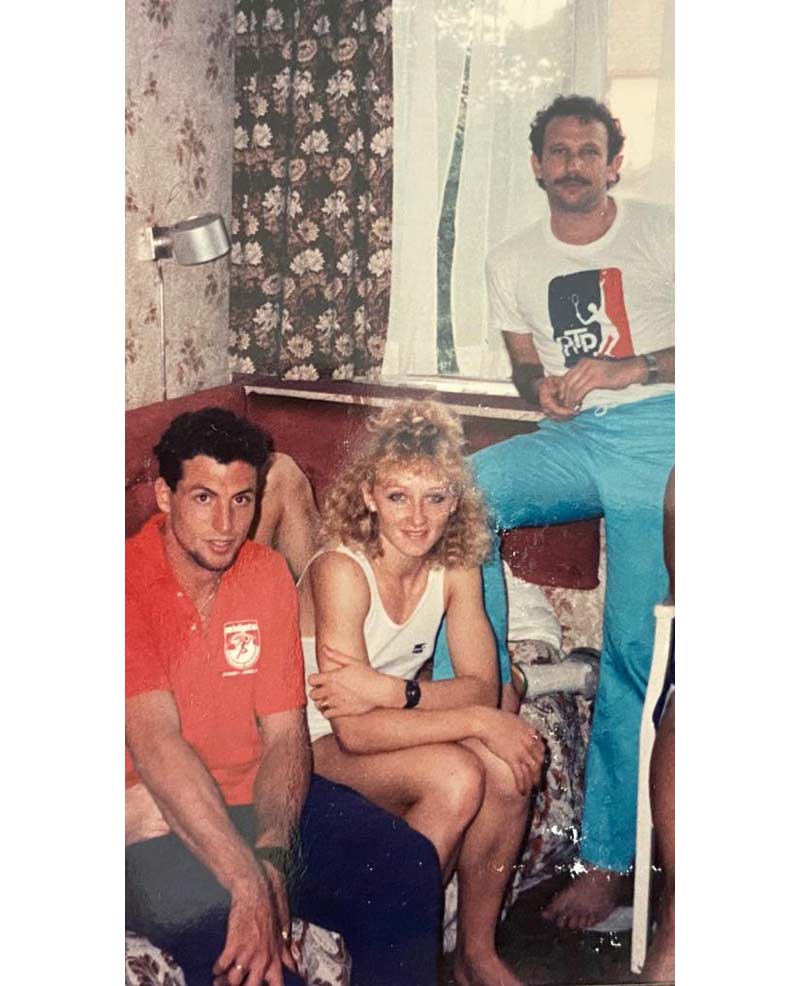

Mike Hurst coached Australian sprinters to qualify for five successive summer Olympic Games from 1980–1996 and one more in 2020. His most successful athletes were Seoul Olympic 400m Finalists Maree Holland (50.24s) and Darren Clark (44.38s), who set NSW State and Australian National Records. Most recently, Hurst coached Rebecca Bennett and Ian Halpin to anchor Australia’s 4×400 relay teams at the 2019 World Championships in Doha.

While pursuing his love of coaching, Hurst worked as a sportswriter for the News Ltd group of newspapers in Australia, for which he reported in-stadium at the first nine athletics world championships (Helsinki 1983 to Paris 2003), seven Commonwealth Games, and six summer Olympic Games.

Freelap USA: The role of tempo is a controversial topic among internet coaches. In order to make a case for or against its use, I think it’s important to define it clearly; so, how do you find tempo work? Is it something you use? If so, how do you integrate it into your program?

Mike Hurst: As I understand tempo from my time with Charlie Francis—who was a great advocate for it—it was anything run at 70% of maximum speed for that distance, or slower. In 1988, I had two athletes make the Olympic final over 400 meters, and we were using a lot of submaximal efforts—but by the definition I’ve just described, it wouldn’t fall into the category of tempo. We spent a lot of time training at the pace of the second half of a 400-meter race, which would normally be an athlete’s best 200-meter time, plus about three seconds. And while the number of repetitions may vary slightly, the recovery was typically a slow 200-meter jog.

We would also use a lot of 300-meter runs, and we would typically do nine repetitions—three sets of three reps—at a pace about 6–8 seconds slower than their best 300-meter time. This session would be done with a 100-meter jog between reps and a very slow 400-meter jog between sets one and two, and then a 400-meter jog AND a 400-meter walk between sets two and three.

We would also often run a session of 12 efforts, three sets of four reps, over 150 meters—these runs would be somewhere between two and three seconds slower than a best time for a one-off rep over this distance. This session would be done with a jog across the infield back to the 150-meter start between reps one and two and reps three and four, a walk across the infield between reps two and three, and a long recovery interval of perhaps 8–10 minutes or so between sets. However, this wasn’t something I was too strict on.

Now, these times are ballpark estimates based upon personal best times, but how close these reps could be completed to personal best levels would depend on things like training age, talent levels, and training surface (we did a lot of training on grass). I see value in this type of work to prevent an athlete from falling apart toward the end of a race, and so we use sessions such as those above to squeeze the envelope and encourage the athletes to become more comfortable with being uncomfortable.

While Charlie, and a lot of those whom he has influenced, stayed away from work between 70%–75% and 90%–95% intensities, in a conversation I had with Abdelkader Kada—coach to Hicham El Guerrouj, the 1500m world record holder—he told me that they did a lot of work in the rhythm of the latter part of the race. I tend to view this as intensive tempo, which we did a lot of, and it is what I prefer; this would sit in that “mid-zone.”

Every now and then, a coach comes along who uses a method that may be considered madness, but then they have an athlete break the world record, and it makes us reconsider what we thought to be true. Share on XThere are great coaches who wouldn’t use this method, and I’ve probably not spent enough time with these coaches while they coach their athletes to understand their reasoning well enough. This is one of the reasons the sport is so fascinating: there’s such a variety of methods that can lead to success. Every now and then, a coach comes along who uses a method that may be considered madness, but then they have an athlete break the world record, and it makes us reconsider what we thought to be true.

Freelap USA: One of the workouts that you perhaps wrote more about on internet forums than others was the 5–6x200m session you had your 400m athletes do. Are you able to please outline the parameters of this session, what led you to implement this session, and some of the things you look for from the athlete and hope to develop?

Mike Hurst: In 1968, Mel Watman put out a booklet regarding the Mexico City Olympics, including an interview with Lee Evans, the 400m gold medalist and the first man to officially break 44 seconds for the event. He said that in his time at San Jose State under Bud Winter, they would do six runs of 200 meters in 23 seconds with a jog-back recovery. As I went down this rabbit hole, I gathered data from Charles University in Prague, which covered races from various championship meets, including the 1982 European Championships. The data showed that a large proportion of 44-flat male 400m runners ran the last 200 meters of a 400-meter race in about 23 seconds, and the 50-flat females often ran the last 200 meters in about 26 seconds.

When I initially started incorporating these 200-meter repetitions into the program, a lot of the athletes were struggling after three runs—but over time, many of them progressed to being able to complete five runs. In 1988, I had Darren Clark and Maree Holland in the individual 400m at the Seoul Olympics. Prior to this, Darren had completed six 200-meter runs off a one-minute-and-forty-second jog recovery in 23 seconds, and I believe I had timed two of them in slightly under 23, and Maree had completed her runs in 26 seconds. This gave me the confidence that they were prepared to run well.

Back in those days, there were four rounds, and I wonder if that played to our advantage because while I felt we had a fairly specific program, it was also based upon a substantial amount of endurance. So, with the back end of the race that I felt this session helped cultivate—and the fact that Darren had run a training PB in a 200m time trial and Maree had run a 200m competition PB in the lead-up to the Olympics by concurrently developing speed and endurance together, largely working at the rhythm of the race—we all felt pretty confident that a good 400-meter race could come together.

Beyond the 5–6 x 200-meter session, I had the athletes go a little more specific when needed by doing two sets of 2 x 200 meters, which would really address the race model. If I had an athlete with a season’s best 200-meter time of 20 flat, they were required to run the first run under 21 flat. After that, they would take two minutes’ rest before running a “rolling” second rep with the intention of it being faster than the first.

Freelap USA: To be a successful 400m sprinter, it’s important to develop the physiological capacities to have a high enough maximum velocity and to endure a speed that is at a relatively high percentage of that maximum velocity. How do you balance your programming to ensure these two aspects are developed within your athletes?

Mike Hurst: Vertically integrating a program, so that all the important qualities could be developed at all times throughout the year, is important, and some of the ideas that initiated my setting up of such a program came from Daley Thompson’s coach, Frank Dick. One thing he said that stuck out, particularly, was that if athletes train in the same rhythm for more than three weeks, they risk becoming locked into what he termed a “dynamic stereotype.” This reinforced my own experience from when I was an athlete, and I could run five or six 200-meter efforts in 22.5, but I couldn’t run under 22 seconds in a one-off effort.

Maybe running much further than 300 meters isn't essential when training for the 400m. By the last 100 meters of a 400m, you’re running so slow I wonder if you want your body used to that tempo. Share on XThis also led me to the idea that maybe it wasn’t essential to run much further than 300 meters when training for the 400m. By the last 100 meters of a 400m, you’re running so slow that it makes me wonder if you want your body used to that kind of tempo. The challenge was balancing both speed and endurance simultaneously while factoring in the right amount of recovery so that fitness wasn’t lost, but injury risk was mitigated.

Taking all this into account, I designed five-week training blocks, which I’ll provide more detail on later. Essentially, the first two and a half weeks had strength and endurance as the primary emphasis, and the second two and a half weeks emphasized speed and power. After completing the five weeks, week six was a “rest and test” week, during which resting was certainly the emphasis! Tests were inserted based on the athlete’s recovery status, and this also dictated the tests chosen, to an extent.

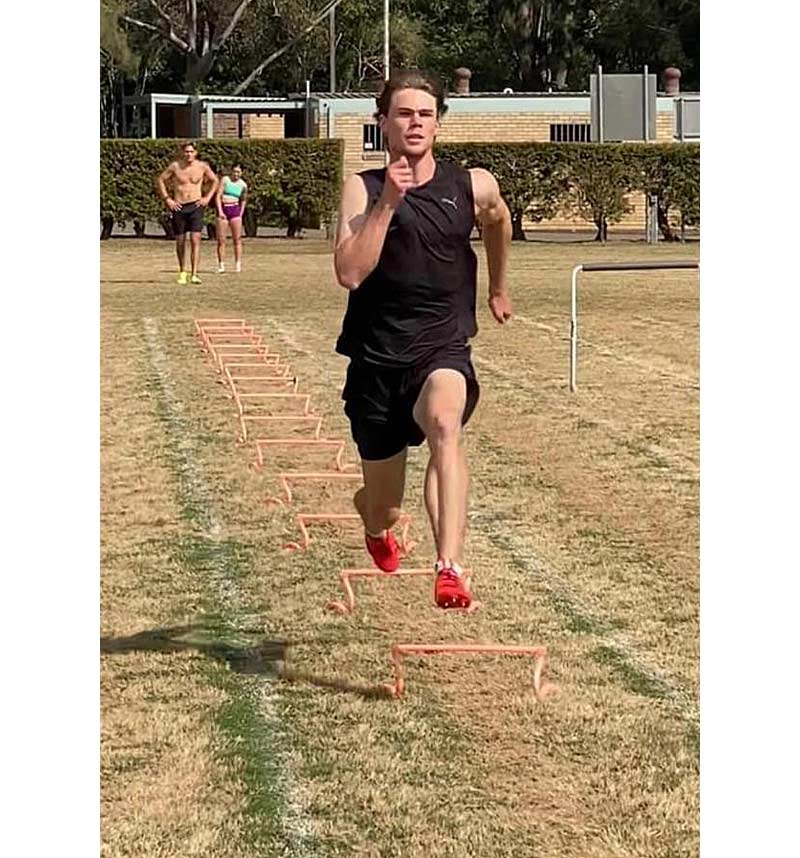

Video 1. Working out at the track.

Within the “speed block,” we would do a lot of things, like flying 30 runs working on entering and exiting the bend. For example, the athlete would build up for 50 or 60 meters and run hard for 20 or 30 meters, and this zone would finish at the end of the straight; they would then maintain this rhythm for another 40 meters or so throughout the first half of the bend. When approaching the exit of the bend, we spent a lot of time working on “dialing up” the intensity rather than flicking a switch to avoid any sudden or abrupt changes to the technique or the physiological demands.

As I mentioned in the previous answer, we built these qualities into a race modeling session, and I think that’s something important to help make these qualities we’re developing more functional. I like to make the analogy that we’ve built and developed the car, and then the race model work is almost like learning how to drive that car!

Freelap USA: The benefits of resisted and assisted sprinting probably contribute to a smaller component of development for the 400m athlete than the 100m sprinter. Are these modalities that you use? What other technology do you find to be useful when coaching 400m athletes?

Mike Hurst: I would love access to a 1080 Sprint, but unfortunately, that is not an option for me and my athletes. Therefore, we make use of hills and sleds for resisted sprints. While I do not implement a great deal of assisted sprinting, I would again use a hill, but I would try and keep the decline at two degrees or less and on a reasonably soft surface as a bit of injury mitigation should the athlete fall.

While this isn’t something I would do now, a funny anecdote is that when I started coaching years ago, I had an athlete, Debbie Wells, running while holding onto the bumper bar of a car! Interestingly, Debbie was a prodigy, representing Australia in the 1976 4x100m Olympic final at only 14 years old!

Another thing I would like to have access to is pacing lights, such as those used in East Germany in the mid-1980s by Wolfgang Meier, coach to 400m world record holder Marita Koch, and also Marie Jose Perec. Obviously, there were some practices taking place in that part of the world at that time that went against the rules of our sport, but they did have some very innovative and ethical practices as well, and I wish I had some pacing lights still, 40 years or so after some coaches were using them. As I mentioned, I value the need to work at the rhythm of the race, and having a tool to help guide the athlete to the correct pace in training so it can be reinforced is something that I would find very useful.

Freelap USA: What does a typical block of training look like for 400m athletes?

Mike Hurst: I use the general preparation phase (GPP) to develop virtually everything except maximum velocity (pure speed). The six-week GPP consists of two and a half weeks of what may be termed “strength and endurance training,” followed by two and a half weeks of speed-power training. These two periods of training may be called “micro-cycles.”

The sixth week is termed “rest and test.” It provides the athlete with a chance to recover and the opportunity to run a few time trials if they feel up to it.

Video 2. We often incorporate light (2kg or 3kg) medicine ball activity into our ballistic warm-up. We do five reps, in turn, of five different types of throw or pass in our activation routine.

We stay in touch with some higher-velocity running during the so-called Speed-Power micro-cycle that occupies the second half of the six-week GPP. However, there is a much greater emphasis on high-intensity training and longer recovery during the many months following the GPP.

We do the six-week GPP block twice. So this is three months of GPP training.

During GPP, I try to develop the strength to finish the last 80 meters of the race. We develop the base, then maintain and further develop a thread of that strength at even more race-specific levels during the pre-season and through the in-comp period.

General Preparation Phase

At the end of the warm-up, five “beach” starts (on grass, prone position, starting at the command of the coach’s clap) over 10 meters are included, followed by five 10-meter bunny hops (double-foot take-offs and landings) with a walk-back recovery.

The strength and endurance micro-cycle: This is the first two and a half weeks of the GPP.

Day 1 is a Sunday.

Week 1

Day Session(s)

- 2–3 x 4x150m. One set = sprint 150 meters and diagonal jog back to start, sprint 150 meters and diagonal walk back to start, sprint 150 meters and diagonal jog back to start, sprint 150 meters and rest. Rest = slowly walking a lap (no more than 10 minutes, if possible), then repeat. This session should be done on a grass track.

- Long hills + weights. (Target 3x2x360 meters long hill in rhythm of 400m race). Recovery = jog down, stretch, and then run a second hill rep. Then, full recovery between sets (up to 45 minutes). This is done on a grass hill at about a 10- to 15-degree incline. This session is modified according to age and fitness, and a reduced session can be just 3 x 1 long hill with full recovery OR 1 x long hill, jog 100 meters back down and wait there, resuming sprint to the top when joined by athletes sprinting from the bottom of the hill.

- Rest (or one-hour gymnastics).

- 5x200m + weights. A 5x200m is done in the rhythm of your race. The ideal target time for each 200 meters is about three seconds slower than your 200m PB or close to the time you hope to run for the final 200m in your ideal 400m. Recovery = ideally a 200m jog or no longer than two minutes. However, many sprinters won’t achieve either the target time or the recovery time for the full five reps initially. I recommend going for the target rep time and then walking the recoveries. If necessary, split the set in 2 x 200 + 200 with, preferably, no more than five minutes between the two sets. (Aspiring elite males will ultimately aim to do 6x200m in 23 seconds; females 6x200m in 26 seconds.) This should be done on a synthetic track but can be done on grass.

- Long hills (same as day 2).

- Jog (15–30 minutes) + weights.

- Rest.

Week 2

- Sprints ladder 350, 300, 250, 200, 150, 100, 60, 50, 40, 30—slow walk-back recoveries. (These sprints should be done in the rhythm of your 400m race. The quality of times should improve as the distance shortens.)

- Jog 15–30 minutes + weights.

- Rest (or one-hour gymnastics).

- 2x (300+150) + weights. Initially, run the 300 meters slightly slower than the final 300 meters of your ideal 400m race. Then, ideally, recovery = 30 seconds. Then, the 150m sprint is done with maximum effort. Modify the recovery to 60 seconds or as much as two minutes for younger or less fit sprinters. Recovery then between sets is full, preferably at least 15 minutes (and potentially more than 30 minutes).

- 5x200m (same as on day 4 of week 1).

- 2x5x100 run-throughs, walk back + weights. This session should be done on grass. The runs are to rehearse relaxation, clean mechanics, and easy rhythm.

- Rest

Week 3

- Long hills (as before).

- 3x3x300m + weights (upper body only). This session should be run on a grass track. Each run is 300 meters with a 100-meter slow jog recovery to complete the lap and then run the next 300 meters, etc., with three reps to the set. Recovery = 100m jog between reps; one-lap jog between sets 1 and 2; one-lap jog followed by one-lap walk between sets 2 and 3.

-

The ultimate target for aspiring elite athletes is to run each 300 meters in sub-50 seconds on grass, but for most athletes, simply completing the task of 9 x 300m in any time at all will be the starting point (as a reference point, Darren Clark ran this session with times of 44 seconds or faster, occasionally dipping under 40.0 for the last rep).

- Rest (or one-hour gymnastics).

- Rest (or warm-up, warm-down).

-

The Speed-Power micro-cycle: the next 2 1/2 weeks of the GPP.

- Track fast, relaxed 300+4×60, 250+3×60, 200+2×60, & 150+1×60. (This session starts the Speed-Power micro-cycle. All reps should be run at race-specific intensity for the distance. Recovery between the long rep and the first backup rep is ideally only 30 seconds. However, this can be modified to suit the individual athlete, but recovery should preferably not exceed two minutes. Recovery between the remainder of reps will be a leisurely walk back. The remaining reps in each set should be a rolling start (possibly with one designated leader dropping a hand as they hit the starting line).

- Jog 15–20 minutes + weights (whole body).

- Rest.

Week 4 (repeats for Week 5):

- 300+60, 50, 40, 30; 200+60, 50, 40, 30; 150+60, 50, 40, 30. Ideally, 30 seconds of rest between long rep and first short rep, as on day 5 of week 3.)

- Field circuit* (about six minutes) + NO WEIGHTS: The field circuit consists of various exercise stations positioned around a grass football field. At halfway on the far side of the field, mark out a series of grid marks, each 5 meters further infield than the previous. The first grid will be 5 meters infield from the sideline. There must be a further five grid marks, each 5 meters further infield than the previous grid mark. *See attached diagram of field layout.

-

The circuit starts in the bottom right corner of the football field and progresses around the sideline to finish in the same place. En route, there are tasks. The circuit starts by skipping to halfway. Then, do 10 sit-ups. Then, continue by skipping to the goal line. Then, do 10 push-ups. Then, bound along the goal line to the opposite corner. Then, do 10 jack jumps (knee to chest). Then skip along the sideline to halfway.

-

Here, things get interesting: Do 10 jack jumps, then 10 sit-ups, then 10 push-ups. Then, sprint toward the center of the field to the most distant mark on the grid. This should be 25 meters from the sideline. Turn on this grid and jog back to the sideline. Repeat the same three exercises (jack jumps, sit-ups, push-ups) for 10 reps each. Then, sprint to the second-most distant grid mark (20 meters away), jog back to the sideline and repeat three exercises for 10 reps each.

-

This process continues until all five grid marks have been run around. Upon returning to the sideline for the last (fifth) time, the athlete should do double-foot bunny hops along the sideline to the corner where the other goal line is reached. The athlete should then sprint along the goal line to the far corner, where the circuit starts. Someone must time the circuit for each athlete.

-

There should be a full recovery—sometimes as much as 45 minutes—before the athlete completes a second lap of the circuit. Usually, the second lap is faster than the first.

- Rest (or one-hour gymnastics).

- 300+150, 150+150, 100+80, 80+60, 60+60 (Ideally, all 30-second b/reps; full recovery between sets. If the wind conditions are impossible, then tempo the long rep and attack the back-up rep to be run with a tailwind) + weights.

- Jog 15–20 minutes.

- 3–6 (2x60m skip, 2x80m sled pull or equivalent light resistance, 2x80m sprint buildups). This is a composite, varying resistance speed-power session. This session can be done on a grass track. Ideally, the skipping is alternate lead-leg high take-offs every third stride. The high skips (or take-offs) should be done on a grassy infield. Sled and the sprint buildups should be done on a synthetic track where possible.

-

Recovery between reps in each two-rep “couplet” is an easy walk back. Recovery between “couplets” is also a walk back. The session is envisioned as a continuous rotation of skip, sled, run (repeat). The sled load can be just the weight of the sled (or tire) itself, or a few kilos can be added. The resistance should not damage the athlete’s running mechanics but merely make it harder for the athlete to achieve “lift,” or triple extension on the run.

- Rest.

Week 6

Rest & Test Week

- Rest.

- Warm-up, warm-down.

- Trials 300m (stand start). Full recovery, then a 150m + weights (lowest reps possible).

- Rest.

- Trials 80m (stand start). Full recovery, then a 200m + weights (as normal, all exercises, for volume at 80%–85% of 1RM).

- Rest.

- Rest.

Repeat the six-week cycle starting from week 1.

That’s the basic outline. You have to monitor the athlete closely. I don’t want to be prescriptive with times because every athlete will vary, depending on training years and ability and commitment. No one will go from being a 50-second runner to 44 seconds in one year (unless they have previously been close to 44 seconds).

I make zero demands during the first GPP cycle. But I use it to calculate (also based on PBs and standard 400m models) what MIGHT be appropriate target times for the reps for each individual.

I make zero demands during the first GPP cycle. But I use it to calculate (also based on PBs and standard 400m models) what MIGHT be appropriate target times for each individual’s reps. Share on XThe second time through the GPP cycle, I ask more of the athlete within reason, based on their capacity. After the conclusion of the GPP, the athletes need to complete a transition phase before entering competition.

The transition phase usually lasts four weeks, never less. Monitor every rep, set, and session in person to make sure fatigue (for the most part) didn’t wreck the run. If so, intervene and go for more rest, change the session, or finish it.

I preferred to do the same week of training four weeks in a row during the transition phase. That way, it was like a little test each week, leading into the first low-key race of the new season.

Transition Phase

Day 1:

Warm-up, ins and outs. 2 x 2 x ins and outs (build up to around 50m, 100% effort for 12 meters, and eventually out to 20 meters, then fast turnover but best relaxation to maintain velocity through a 20m exit zone (50-20-20).

There should be good recoveries, maybe 8–10 minutes between reps. Then, there should be 10–15 minutes between the two sets. Then, a full-ish recovery of, say, 15–20 minutes before the second element of the session, which is a sequence of stand, crouch, fly runs from 30–60 meters.

(In sequence: standing, crouching, flying)

3 x 30m, 3 x 40m, 3 x 60m

Warm-down.

……………………..

Day 2:

Warm-up (no ins and outs).

5 x 100m buildups on a bend.

4 x 150. (In this sequence: tempo, first 150m, diagonal jog back to start, fast second 150m, diagonal walk back to start, tempo third 150m, diagonal jog back to start, fast fourth 150m.)

+

Weights.

…………………….

Day 3:

Active rest: Sometimes gymnastics, one hour of mostly proprioceptive routines, such as tumbles emerging into a vertical jump with 360-degree rotation around the vertical axis and land facing the same direction as you emerged from the tumble. Many of these combinations included horizontal rolls (performed with arms and legs outstretched; no use of arms permitted in initiating or maintaining movement).

Full body deep-tissue massage.

…………………….

Day 4:

Warm-up, 2x2x ins and outs (as Day 1).

Then all flying:

300m, 250m, 180m, 150m, 120m. (Sometimes it was 260, 180, 160, 140, 120).

These are usually with partner(s), usually with about 10–12 minutes of recovery, but more if desired. The athletes at this stage of their season are told not to fight for something (speed) that isn’t there yet. Equally, giving them 10 minutes or a 30-minute rest between reps won’t really improve the speed of their reps, but the longer rest does pose a risk of the athlete getting cold or tight.

The sprints are about rhythm and position (triple extension through the hip, knee, and ankle joints during track contact beneath the torso).

+

Weights.

…………………..

Day 5:

Warm-up (no ins and outs).

400m Race Modeling: 4 x 100. (Wherever most needed, but at this stage of the year, it is usually down the back straight and into the turn through the 200m start area, finishing at the water jump.)

2 x 200m + 200m

First set:

First 200m at intended 400m race split. Generally speaking, the target time for the first 200m at the 400m race pace will be one second slower than the current 200m PB (mid-21 seconds for elite males, high 23 to low 24 seconds for elite females).

Two minutes of recovery.

Second 200m at 100% of whatever is left.

FULL RECOVERY between sets (often up to 45 minutes)

Second set:

First 200m tempo in about 23 seconds for elite male/26 seconds for elite female.

Two minutes of recovery.

Second 200m at 100%, aim to negative split (i.e., run the second 200m faster than the first 200m of this set).

……………….

Day 6:

Warm-up.

Warm-down.

+

Weights (usually upper body and torso work only).

Chiropractor/Physiotherapist appointment: to check alignments and adjust if needed.

…………………

Day 7:

Race. (4x400m relay usually, certainly nothing shorter, and no individual races until week four of the transition block has been completed.)

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF