I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: the World Athletics biomechanical reports are a treasure trove for coaches and sports data mavens. The 2019 Doha reports may not be available yet, but the reports from Berlin 2009, London 2017, and Birmingham 2018 offer a wealth of data for each track and field event. I used the reports about the long jump to write Building a Better Technical Model for the Long Jump, in which I made evidence-based recommendations for training certain fundamental skills in the event. Analyzing someone else’s data is never easy, so I told myself to take a long break before doing it again. I also told myself to stay away from the biomechanical reports about pole vault because the pole vault is an excessively technical event.

The World Athletics biomechanical data reports on pole vaulting offer critical perspectives which the naked eye can rarely capture as effectively. Share on XWhile writing a different piece about pole vault, I needed to check the reports from the Berlin, London, and Birmingham World Championships for a minor reference. I couldn’t help getting pulled into writing something new, and what you’re about to read is the result.

The reports are still a work in progress. A few variables may fall short of their intended assessment, but overall, the reports offer critical perspectives which the naked eye can rarely capture as effectively. A basic understanding will support coaches with more critical analysis and improved feedback for their athletes. Though pole vault seems like the wrong jumping-off point, the event is an ideal model for a case study because ample opportunities exist to collect data. I was pleased to find many similarities between the reports on pole vault and long jump:

- Runway velocity

- Length of steps

- Takeoff angle

- Vertical displacement of an athlete’s center of mass

- Performance marks

These include familiar variables and, expectedly, some new ones as well. Each biomechanical report offers raw data, graphical analysis, and written commentary for the men’s and women’s competition finals. Speed correlates with performance in almost all track and field events, and the pole vault is no exception. The top athletes consistently demonstrated the greatest runway velocities. But that relationship can be further broken down into instantaneous velocities in the last three steps before takeoff, for which more meaningful technical considerations appear. This correlation is not perfect, but it holds up quite well. Runway velocity is one of the variables present in all the reports.

Assessing Stride Pattern

The length of the last three steps before takeoff offers preliminary insight into an athlete’s favored technical model. The ratio between lengths of the penultimate and last step demonstrates how the athlete prepares to jump up. A longer penultimate step followed by a shorter last step most effectively allows an athlete to jump into the air—with or without a pole in hand. My long jump article directly addresses this claim and supports it with evidence from the same World Championships. The pole vault reports present a similar variation in the stride pattern data. For example, 12 out of 15 male vaulters and 8 out of 11 female vaulters from Birmingham 2018 relied on a long-short stride pattern at takeoff. In London 2017, 8 out of 9 male vaulters and 10 out of 12 female vaulters relied on this pattern.

A vaulter’s preparation to jump up is important to a vertical event while the timing of their takeoff can greatly diminish the efficacy of their jump. Professional pole vaulters seem to debunk this claim due to their impressive speed and strength. While they might rely on an even or a short-long stride pattern—which produces a less effective jump—they still manage to clear a high bar. Many athletes and their coaches might call this style, but style is no reasonable excuse for what runway velocities reveal and the naked eye cannot see.

In the early 1980s, pole vault coach Vitaly Petrov introduced and promoted the free takeoff, which requires the vaulter to jump off the ground slightly before the pole tip hits the back of the plant box. The free takeoff was widely used and popularized by Petrov’s athlete and former WR holder Sergey Bubka, who is still one of the most decorated track and field athletes of all time. The Petrov Model (also known as the Champion Model) advanced pole vault technique because it included this free takeoff.

Although a long-short stride pattern supports the free takeoff, the biomechanical reports show it does not correlate with a free takeoff. #PoleVault Share on XAlthough a long-short stride pattern supports the free takeoff, the pattern does not correlate with a free takeoff according to the biomechanical reports. For example, the American record holder and Olympic silver medalist Sandi Morris relied on a long-short stride pattern in London 2017 but favors taking off after her pole tip hits the box. This is known as taking off under the pole or getting ripped off the ground. According to still-frame analysis in the 2018 report, Morris does not rely on a free takeoff in this jump because her pole has already begun bending while her takeoff foot has not left the ground. Morris is a decorated vaulter and this style works for her, but I don’t recommend beginners learn to pole vault with the same style.

The 2018 report reveals that Brazilian Thiago Braz da Silva, the 2016 Rio Olympics gold medalist, relies on a free takeoff and a long-short stride pattern. It should come as no surprise that Petrov is his coach. Another iconic athlete in the Birmingham report is former WR holder Renaud Lavillenie, who won the pole vault in the 2012 London Olympics but lost to da Silva in 2016. Though I’ve watched Lavillenie compete many times and know his jump well, I had thought he did not rely on a free takeoff. I was mistaken. Lavillenie relies on an unusual, short-long stride pattern, but the 2018 report’s still-frame analysis reveals he jumps with a free takeoff. This is also evident in his 2014 world record.

Timing the Takeoff

The data from Morris, da Silva, and Lavillenie call into question the assumed correlation between stride pattern and takeoff. These three profiles confirm the need for a new variable, which measures the time between an athlete’s last contact with the runway and their pole tip colliding with the back of the box. When the difference is positive, the athlete jumps up before the collision. This would qualify as a free takeoff. When the difference is negative, the athlete jumps up after the collision—under the pole typically. The combination of this time difference and the last three steps provides valuable assessment for all athletes and coaches. I recommend adding this time difference variable to future reports.

Pole vault needs a new variable to measure time between an athlete's last contact with the track & the pole tip colliding with the back of the box. Share on XSome pole vault coaches value using a takeoff mark on the runway. In my coaching, I don’t find catching the last step on the runway more valuable than watching the vaulter transition from the runway into the air, so I generally ignore this mark. Other coaching tools, like mid-marks, glean similar information. However, the London 2017 report measured the displacement of the athlete’s top handgrip position relative to the last step, which the reports called takeoff foot position. The naked eye cannot easily observe this measurement, and I found the analysis very useful for the plant.

Unfortunately, these measurements were not included for each athlete. If the biomechanical project team chooses to include takeoff foot position in future reports, it will help determine which planting technique an athlete favors in their jump. Displacement in front of the foot would suggest that the athlete favors a forward plant, characteristic of Coach Roman Botcharnikov’s 640 Model. Minimal displacement, with the top hand directly above the foot—or displacement shifted behind the foot—would, instead, suggest the athlete favors the more traditional Petrov Model. Each model offers its benefits and drawbacks. While the Petrov Model is the most widely used, the 640 Model is safer and easier to learn. A trained eye knows how to determine which technical model an athlete uses, but the takeoff foot position will assist its confirmation. If the takeoff foot position seems extreme in either direction, then I recommend filming several jumps to confirm the assessment before addressing it with the athlete.

Capturing the Plant

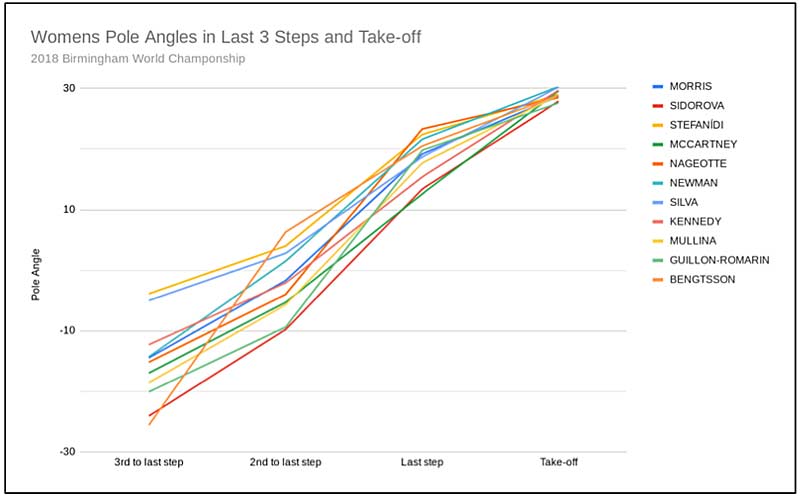

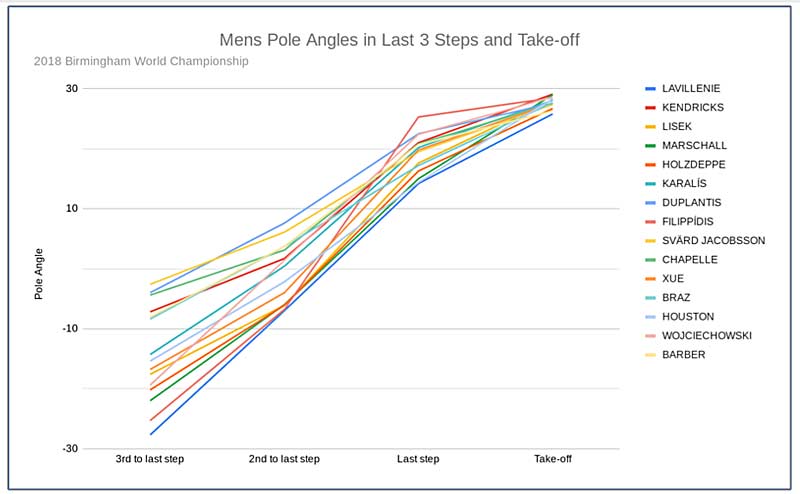

In the pole vault, coaching motions is usually better than coaching positions, but it’s incredibly hard to find reasonable data that assess motion better than the eye. Pole angle at takeoff is not a useful variable because these measurements are nearly identical for every athlete. More fruitfully, the 2018 report includes pole angles before takeoff. This data captures the planting motion because the change in pole angle indicates how quickly the vaulter plants the pole over the last three steps. In Images 1 and 2, notice how the change in pole angle is gradual for most vaulters in their final steps. Steeper slopes, or sharp increases relative to the previous step, suggest the vaulter plants too quickly. This is known as punching the pole or flipping the pole. Seven out of the 26 vaulters plant their pole too quickly when compared to the smoother, more general trend apparent from the other 19. Pole angles before takeoff were included in the 2018 report but not the 2017 report.

Data about pole angles before takeoff captures the planting motion & indicates how quickly the vaulter plants the pole over the last 3 steps. Share on X

Like all phases in the pole vault, the plant should precede and transition into the takeoff phase smoothly and gradually. Punching or flipping can create unnecessary resistance and loss of velocity at takeoff. One way to minimize this loss is by letting the pole drop by its own weight and extending the bottom arm to guide it into the box. I found the pole angle data useful, but not completely necessary. Coaches can easily observe how smoothly their vaulters plant the pole. Analysis of professional vaulters has its value in understanding proficient or deficient archetypes, but possibly no more than that.

Applying Vertical Variables

When I noticed the reports included push height, I was thrilled. Then I discovered that push height measures “the vertical distance between the center of mass at pole release and peak height” (Bissas, 2017). Although the rise of a vaulter’s center of mass is critical in assessing technical efficiency, push height addresses this motion insufficiently because it does not account for the displacement above the top handgrip. If a vaulter produces substantial push height but their grip is relatively high, they are not jumping efficiently. Whereas a vaulter who produces average push height and holds the pole relatively low can still create an extremely efficient jump.

A vaulter who produces average push height and grips the pole relatively low can still produce an extremely efficient jump. Share on XThe vertical difference between a vaulter’s top handgrip and the bar height is a more valuable tool. This is known as push-off. I appreciate that the 2017 reports include grip height, but this data was not subtracted from each vaulter’s bar clearance to generate a push-off variable. Vertical distance variables like push height, pelvis clearance height, and swing height miss the mark. For example, Holly Bradshaw, Lisa Rizyh, and Yarisley Silva all cleared 4.65 meters with similar vertical displacement measurements. Bradshaw and Rizyh are comparable in height, and Silva is ten centimeters shorter. However, in Silva’s best jump, she spent considerably less time in contact with the pole than her two opponents.

This profile calls into question the utility of such vertical variables, when other factors, like runway velocity, may deserve greater consideration for assessing technical efficiency. Other vertical variables, like pelvis height, may offer fans a wow factor, but bar clearance matters most. The project team should present variables, like push-off and pole angles, more explicitly, while eliminating confusing variables, like push height or pelvis height.

The 2018 commentary acknowledges that the transition from the runway to off-the-ground mechanics continues to perplex the investigative team. The fastest athletes on the track do not always produce the best jumps because “a considerable amount of the kinetic energy from their approaches was not stored in elastic structures like the bending pole or in muscle-tendon stiffness” (Bissas, 2018). This may derive from “ineffective absorption in body structures,” which relates to the athlete’s favored technical model (Bissas, 2018). In all track and field events, evidence-driven skepticism like this should be an opening to define new variables and collect more data.

Although I’m encouraged by its inclusion, I think the project team misapplied their vertical displacement data from London 2017. A year later, the 2018 commentary recognizes an absence of “data concerning the upper jump phases for this competition” (Bissas, 2018). While this statement is true, I find it misleading. The 2018 commentary states that it “cannot discuss the complete mechanical efficiency of the athletes” when the very same data was collected in the year before (Bissas, 2018). The 2018 reports exclude this data, rendering limited analysis for motions off the ground, and recommends concentration on the “approach, pole plant and takeoff” (Bissas, 2018). Again, I agree—with some reservations. Grip height and bar clearance are the two most valuable measurements for the greater pole vault community.

Grip height and bar clearance are the two most valuable measurements for the greater pole vault community. Share on XGrip height is one of a few pole specs worth including in a biomechanical report. Pole length and weight rating provide perspective on an individual’s seasonal or historical progressions. These specs can also compare performances between athletes in one competition. For example, a vaulter who clears a higher bar with a shorter pole is a more technically efficient jumper because they produce greater push-off than the opponent on a longer pole. They may not be faster or stronger than their opponent, but certainly more efficient. A vaulter who jumps on a pole with a higher weight rating when lengths are equivalent is usually heavier or faster than their opponent who jumps on a lighter pole. In both examples, I assume the two athletes clear the same height. Hopefully, runway velocities will corroborate these relationships. Grip height is nearly a proxy for pole length, but weight rating is harder to record without athletes sharing this information ahead of, or during, the competition. Neither pole length nor weight rating are included in either years’ reports. These specs deserve greater scrutiny and attention in the future. More data is always better.

Recognizing Limitations

I must recognize the limitation of my analysis. The data in each biomechanical report only represents the best jump from each athlete. The compiled results show that every athlete took at least three jumps in the competition. The best jumps may not, in fact, represent the common practices of each athlete. Even in my ignorance of any of the innumerable emotional, physical, or environmental factors present, it’s impossible to know how each athlete performed relative to prior competition without the data to support such analysis.

Only 72 total vaulters competed in the Berlin, London, and Birmingham finals. This number includes both male and female athletes. While 72 unique attempts to clear a bar provides more than enough data for analysis, this number compares poorly to the total number of clearances by all athletes when summed together. Between all three world championship finals, 72 athletes cleared a bar 194 times. Although 122 unique jumps may have been captured for analysis, they were never presented or published. I view these limitations as both reductive and motivating. They make me skeptical of my conclusions from the reports. The numbers reveal that there is more to learn from this spectacular event.

Hopefully, continued reporting & systematic compilation of data will cement some technical skills into a fundamental learning model for the pole vault. Share on XPole vault has evolved several times since its introduction in the 1896 Olympics. From rigid, wooden poles in the early days to flexible fiberglass of the modern era, technical proficiency has always lagged behind pole material innovation. While our understanding of fundamental skills like runway velocity, preparation for takeoff, and a smooth plant has progressed gradually, comprehensive biomechanical reports have never existed for the World Championships until this past decade. Hopefully, continued reporting and systematic compilation of data will cement certain technical skills into a fundamental learning model for the pole vault. In this learning model, I do not mean the Petrov Model, the 640 Model, or any technical model preceding either of these. Runway velocity, preparation for takeoff, and a smooth plant are simple necessities for a good jump. They are embedded within every technical model because they are fundamental skills to the event.

Beginners should focus on fundamental skills—push-off, stride pattern & smooth plant—& avoid emulating techniques of elite pole vaulters. Share on XThe 2017 women’s’ commentary states, “the model should be modified to the athlete” (Bissas, 2017). While I agree with this statement, it applies mostly to athletes with impressive strength and speed—not beginners. I fear it encourages young vaulters to emulate techniques they are neither strong nor fast enough to master in their early years. Faster athletes can grip higher. Stronger, more flexible athletes can take off under the pole more reliably. Beginners should focus more on fundamental skills like push-off, stride pattern, and a smooth plant until they reach their full height, adult weight, and genetically predetermined body proportions.

Thinking Bigger than the Pole Vault

It’s worth noting that the 2017 pole vault reports measured more variables than the 2018 reports did, but they do not explain scaling back their data collection. If it’s because certain variables need more clarity or scrutiny as to which serve the pole vault community best, then I’m encouraged by this reflective process. I hope some of those missing variables from 2017 will return to future reports. A wealth of stories exists from a century of pole vaulting, but very limited data exist comparably in the public domain. Data can help parse credible coaching practices from sheer dumb luck. While stories and anecdotes might inspire us to embrace new ideas, data drives innovation and sustainable improvement.

Data can help parse credible coaching practices from dumb luck. All coaches should read at least one of the World Athletics biomechanical reports. Share on XI recommend all coaches read at least one of the biomechanical reports. The expanded scope of biomechanical analysis from London 2017 and Birmingham 2018 offers an opportunity to improve your professional practice. The reports provide a worthy service to the pole vault, as well as our wider athletic community. I look forward to the Doha 2019 report, and many more in the future!

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF