In this article I will outline the approach used in technique analysis with Finnish national swimming teams. The senior team usually consists of approximately 20 swimmers, among whom there are currently a medalist from the World Championships and several medalists in European Championships. In this mix there are several athletes hoping to take the next step to international elite level, while the junior teams are composed of 20-25 promising swimmers between the ages of 15 and 17 years old.

I’ve been working as a technique analyst for both senior and junior national teams in Finnish Swimming since 2013. My job is to provide feedback on national team camps through biomechanical analysis to give athletes and coaches information on each swimmer’s strengths and weaknesses as related to international level performance. In my time as a technique analyst for those teams, we have used video, speed measurements, and Trainesense SmartPaddles as tools to analyze a swimmer’s performance. Of these tools, the SmartPaddle is the newest addition to our arsenal.

The Trainesense SmartPaddle measures hand force, hand speed, and the direction of the force in water, which provides us with useful information about our athletes’ strengths & weaknesses. Share on XThe Trainesense SmartPaddle measures hand force, hand speed, and the direction of the force in water, which provides us with useful information about our athletes’ strengths and weaknesses. Traditionally, power in water has been measured with a wire attached to the swimmer’s hip—thus giving the total force produced by the swimmer’s movements—but there hasn’t been an easy way to go into details regarding which parts of the swimmer’s stroke produce that power and which parts should be further developed to swim even faster. Using SmartPaddle, we have access to all that data.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9118]

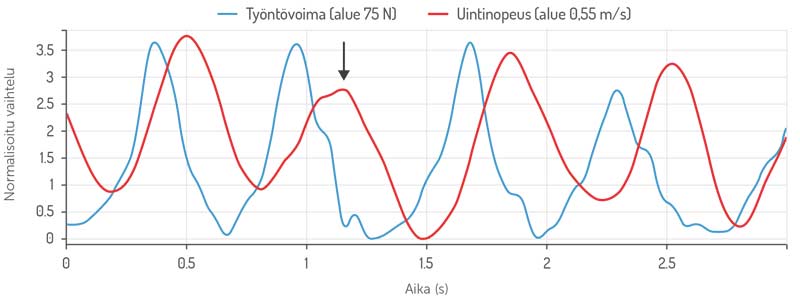

As a part of our validation process with the SmartPaddle, we measured both hand forces and swimming speed simultaneously to see the interplay of force and velocity. In figure 1 below, there is an example of a swimmer’s hand force and speed. This graph clearly shows that there is a connection between the force measured from the hands and a swimmer’s speed in freestyle swimming.

It’s also interesting to note that there is a 0.1-0.2 second delay between force increase and velocity increase. This added mass effect is evident in all movement, but I believe that in swimming it is one of the key reasons why swimming fast is so difficult for most people. It takes time for a human body to accelerate in water, meaning propulsive force in a single stroke should be exerted for 0.4-0.6 seconds per stroke to reach high velocities. This requires some patience and is somewhat counterintuitive if you consider that in human natural locomotion (sprint running), the ground contact time is only 0.1 seconds.

In essence, swimmers need to learn to hold onto the water long enough to accelerate the body forward and fight their natural, land-based habit of producing force as explosively as possible.

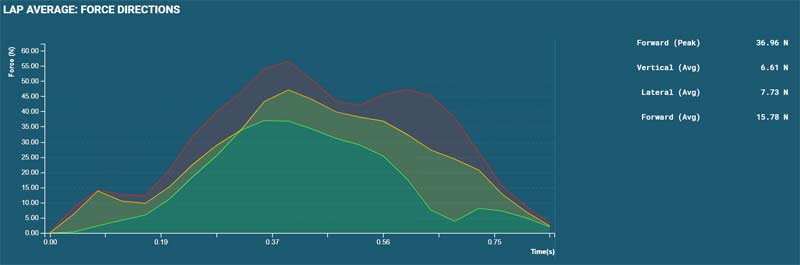

Thus, a continuous propulsive force phase of 0.4-0.6 seconds per stroke, where most of the power is directed back toward the swimmer’s feet, is one of the parameters that I check first during our national team camps since it’s one of the most fundamental aspects of swimming fast. This applies to freestyle, backstroke, and butterfly. However, in the breaststroke, less force is produced backward due to the sculling motions prevalent in the breaststroke pull.

Limiting Factors for Creating Force in the Water

It is kind of surprising how many swimmers can’t produce a consistent propulsive force during the stroke. This uninterrupted force production phase requires an ability to sense small changes of pressure in the palm of the hand and forearm, as well as the ability to control the force produced by the swimming muscles. In my experience, these two components are the main ingredients for a good feel for the water, and they should be trained accordingly.

The abilities to sense small changes of pressure in the palm and forearm and to control the force produced by the swimming muscles are the main ingredients for a good feel for the water. Share on XSome common difficulties in producing propulsive force in freestyle are:

-

- Exerting too much of the force downward instead of back toward the feet.

-

- Muscling through the stroke, so that the swimmer produces a lot of power in the beginning of the stroke, but the force tapers off too fast. (This results in too short of an impulse for accelerating the body forward.)

The first problem is usually seen in swimmers with a lot of upper body strength and/or bad shoulder and thoracic spine mobility. Pushing down in the beginning of the stroke increases the feeling of pressure in the palm and forearm, giving the swimmer a feeling of a powerful stroke. However, most of the force is used to lift the swimmer’s upper body higher in the water instead of moving forward faster. This downward push is also detrimental to shoulder health and can lead to injury. Poor mobility leads to a similar technique error due to difficulties in keeping the hand in a streamlined position after the entry.

It is worth noting that in SmartPaddle data, the best swimmers usually produce a little force downward in the beginning of the stroke as well, but the magnitude of the force is small. With good swimmers, it seems their hands are active after entry into the water, but excessive downward push is avoided.

The second issue is typical in swimmers with good endurance, but little patience. The problem is that they accelerate their hands too fast in the beginning of the stroke. After this aggressive catch, hand speed usually starts slowing down mid-stroke, resulting in a loss of pressure in the hand and, consequently, the loss of propulsive force as well. This early force peak in the stroke leads to too short of an impulse to accelerate the body forward optimally.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9120]

The graph showing force and velocity curves also has an interesting detail just after the one-second mark (highlighted by an arrow in the picture). Here, the swimmer’s stroke has produced similar force as the prior stroke, but the gain in speed is less than it had been previously. Intrigued by this, I checked the video to see a reason for the discrepancy and found that during that particular stroke, the swimmer was breathing, and his kick was too wide to balance the breathing action. Thus, the increased resistance during breathing negated some of the work done in that stroke.

This specific detail in that one swimmer’s performance data highlighted a fundamental law of swimming for me:

-

- Backward force created by the hands increases forward velocity unless increased resistance due to technical errors negates it.

If the data shows a consistent force production phase that lasts long enough, and the swimmer produces high enough peak forces but the swimming speed is still lacking, the usual reason is that the swimmer is creating too much drag. Therefore, every now and then it is a good idea to supplement SmartPaddle use with underwater video to determine whether the swimmer’s body position or limb movements produce unnecessary drag.

Every now and then it is a good idea to supplement SmartPaddle use with underwater video to determine whether the swimmer’s body position or limb movements produce unnecessary drag. Share on XUsing Force Data to Assess Performance

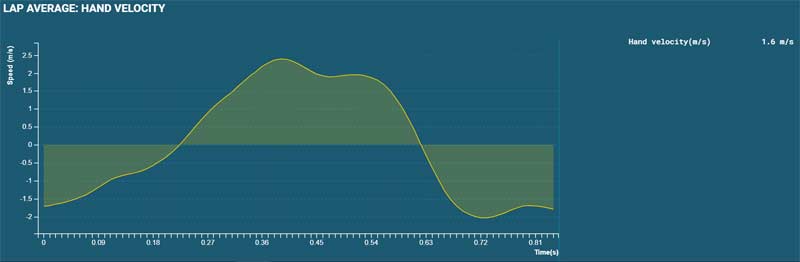

Coaching literature commonly highlights the importance of accelerating the hand throughout the stroke. In fact, difficulty in smoothly accelerating the hand is usually the reason why a swimmer is unable to produce force consistently through the underwater part of the stroke. The graph below details both hand speed and hand force.

From this graph, force levels clearly start to drop off as soon as hand velocity decreases in the pull. Even if the swimmer’s hand starts accelerating again after a slow phase, the forces produced during this second fast part are less than those produced in one smooth, accelerating stroke. Therefore, smooth hand acceleration in the underwater part of the stroke is one of the factors I look for in the SmartPaddle data when evaluating a swimmer’s performance.

The difficulties in maintaining steady pressure on the hand by accelerating it throughout the stroke are, in my opinion, partly caused by the way swimming is taught. Coaches and analysts (myself included) love to talk about different phases in the stroke to highlight certain key positions—for example, the high elbow position in freestyle. Even though these positions are important, coaches should take into consideration that from the point of view of hand acceleration and force, the transitions from one phase to the next are usually where we see a drop in hand velocity and force. Thus, concentrating heavily on the correct execution of one part of the stroke can be detrimental to executing the whole stroke with correct hand acceleration—and this tendency should be countered with enough skill training where the focus is the whole stroke as one fluid motion.

Addressing Left-Right Asymmetries

One interesting aspect of swimming performance that we can monitor with the SmartPaddle is the difference between left- and right-hand strokes. It has been previously reported that 50% of top-level swimmers (FINA points classification over 900 points, meaning roughly top 10 in World Championships) participating in one study had significant left-right asymmetry in their freestyle strokes.1 Fixing some of this asymmetry seems like a promising way to improve performance, even with elite-level swimmers.

In technique analysis, this left-right difference is sometimes visible in the video, but usually only with less skilled athletes. Side differences can also be evaluated through velocity measurements in freestyle and backstroke if the system used is precise enough. However, with a velocity-based method, you can’t be sure whether any speed discrepancy between the left and right side is due to a force difference between the respective hand strokes or a different level of drag during those strokes.

Without the SmartPaddle, there isn’t an easy way to verify left-right force asymmetry in butterfly and breaststroke. Share on XAdditionally, without the SmartPaddle, there isn’t an easy way to verify left-right force asymmetry in butterfly and breaststroke. For example, I have previously seen a significant hand force asymmetry in a breaststroker who is a medalist in World Championships. Without the force data, we wouldn’t have had any way of knowing this is the case.

When trying to identify and fix significant left-right asymmetry in swimming, there a few things to take into consideration:

-

- It is natural that some level of difference will remain, due to strength difference between the dominant and non-dominant side.

-

- Also, especially in freestyle, the technique usually isn’t totally symmetrical due to breathing action. It is quite common that the stroke executed to the breathing side is stronger due to hip and shoulder rotation assisting in force production.

Despite these factors, in my experience it is fairly common to have simple and fixable asymmetries in a swimmer’s stroke. Sometimes these issues arise from a faulty movement pattern and are clearly technical in nature. There are, however, many cases where swimmers have difficulties activating latissimus dorsi or scapular muscles. Therefore, it’s a good idea to conduct regular screening by physiotherapists to identify and correct such muscle activation issues.

From Technical Analysis to Results in the Pool

In this article, I have outlined my way of analyzing swimming technique with SmartPaddles. In essence, I look for sufficiently long force production time and smoothly accelerating hand speed in both hands.

[adsanity align=’aligncenter’ id=9122]

With national teams, I supplement SmartPaddle data with speed data and video to give as objective a view of an athlete’s technique as I can. After that, we look at the data and videos together with the athlete and the coach to find ways to improve. For example, with one junior national team athlete, based on the data and the videos, we have been going for a shallower trajectory for the right hand since his too-deep stroke pattern made him lose propulsive force in the latter half of the stroke. During this process, we have observed a 17-centimeter increase in stroke length in one year and corresponding increase in submaximal swimming speed, and we’re excited to see how this translates to performance in upcoming meets.

In processes like this, I find SmartPaddle and speed data crucial, since everyone (including me) has their own ideas of how to go forward, but measurable facts are the thing keeping us on the right track.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Formosa D., Mason B., and Burkett B. “The force–time profile of elite front crawl swimmers.” Journal of Sports Sciences. May 2011; 29(8): 811–819.