As the winter season approaches, so does the emergence of various illnesses (i.e., upper and lower respiratory infections) that are associated with gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. When faced with this type of disorder, athletes usually seek care from their family or team physicians, who often prescribe an antibiotic for the treatment of these bacterial-related infections. A familiar prescribed medication is the fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics, which includes medicines such as Ciprofloxacin and Levaquin. When there is a preference for the prescribed fluoroquinolones, it appears that it stems from their excellent gastrointestinal absorption, superior tissue penetration, and broad-spectrum activity.

The athletic team rehabilitation staff, strength and conditioning (S&C) professionals, and sport coaches should all be made aware of the potential risks of prescribed fluoroquinolones such as Cipro and Levaquin with respect to both cause and potentiation of tendinopathy, which is described as the presentation of pain when associated with tendon loading1. In recent years, medical professionals have a much-improved awareness and appreciation of the concerning association between fluoroquinolones and tendinopathy. However, I’ve noticed that our physical therapy facilities continue to receive referrals with active patients and athletes taking this classification of medication for their illness. This is also true of some of the recreational and competitive athletes who we train at our athletic performance training center.

The Achilles Tendon

The gastrocnemius and soleus (calf) muscles converge to form one strong band of fibrous tissue that emanates as the Achilles tendon at the distal aspect of the calf. The tendon then inserts distally into the posterior aspect of the calcaneus (image 2). The Achilles tendon is the largest and strongest tendon in the body. Its anatomical integrity is essential for not only activities of daily living (ADLs), but for ideal athletic performance as well. This tendon plays a critical role in the athlete’s elastic abilities, resulting in maximal propulsion (i.e., linear velocity, jump height, etc.), reactive competences, deceleration, and change of direction.

For example, from 2009 to 2014, there were 80 reported Achilles tendon tears in National Football League (NFL) players with an overall return to play rate of 61.3%.3 It has also been reported that 79.4% of all NFL athletes return to play after an orthopedic surgical procedure; however, 72.5% return to play after an Achilles tendon repair, with an average recovery time of 375 + 130 days4. Those NFL athletes who returned to play had significant decreases in performance postoperative season 1 when compared with preinjury values.3,4 This is not to insinuate that these Achilles tendon injuries were due to prescribed fluoroquinolones, but to express the significance of this type of injury.

Regardless of the sport of participation, the concern persists that Achilles tendon injuries may result in not only diminished athletic performance, but potential tragedy for an athlete’s career.

Fluoroquinolones and the Achilles Tendon

Fluoroquinolones are an effective antibiotic that are well absorbed when taken orally and have an extended half-life; thus, dosing once or twice daily can be very effective.8 Fluoroquinolones display a high affinity for connective tissue, particularly in cartilage and bone. The first fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy was reported in 19839, with many additional subsequent scientific studies demonstrating the concern for Achilles tendon pain and, at times, rupture. The most common presenting symptom of fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy is pain. This tendinopathy pain is usually of sudden onset and may be accompanied by acute signs of inflammation and swelling.10 Achilles tendon ruptures may be preceded by pain, but half of tendon ruptures have occurred without warning.11

Scientific publications have also demonstrated the Achilles tendon is the principle tendon affected in 89.8% and 95% of cases of fluoroquinolone-related tendinopathy and rupture, respectively.11,12 The high stress applied to this tendon due to its weight-bearing role is thought to be the foundation for the high prevalence of injury to this anatomical structure. Compared with the use of other prescribed antibiotics, the use of fluoroquinolones carries a 3.8-fold increased risk of Achilles tendinopathy.13 These related tendinopathy symptoms can be present within hours of the initiation of treatment and last up to six months after the cessation of treatment. Withdrawal from fluoroquinolones after the initial onset of tendon pain and inflammation does not immediately restore tendon integrity, as the affected tendon(s) can become symptomatic and still possibly rupture many months after the completion of treatment.

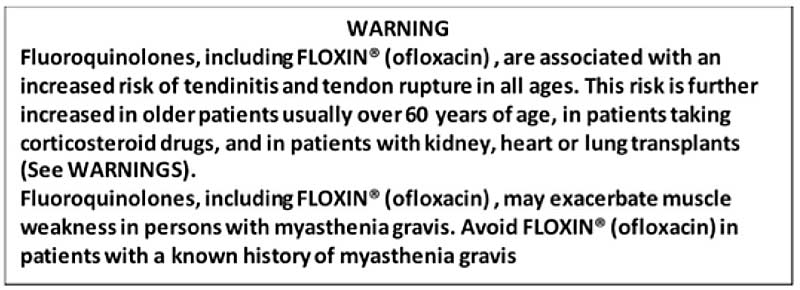

Compared with the use of other prescribed antibiotics, the use of fluoroquinolones carries a 3.8-fold increased risk of Achilles tendinopathy. Share on XOver time, sustained scientific evidence continued to elevate the concern of the commonly administrated medications of the fluoroquinolone synthetic antibiotic drug class for increased risk of tendinopathy and possible tendon rupture, resulting in the eventual placement of a stated medication warning on the label itself (image 4).

Adverse Fluoroquinolone Consequences Are Not Limited to the Achilles Tendon

Although I have placed the emphasis of this discussion on the Achilles tendon, the adverse effects of fluoroquinolones have been reported in other tendons of the body as well. These include, but are not limited to:

- Peroneus brevis

- Patella tendon

- Adductor longus

- Rectus femoris

- Triceps brachii

- Finger and thumb flexor tendons

- Supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons of the rotator cuff

- Tendons of the hip

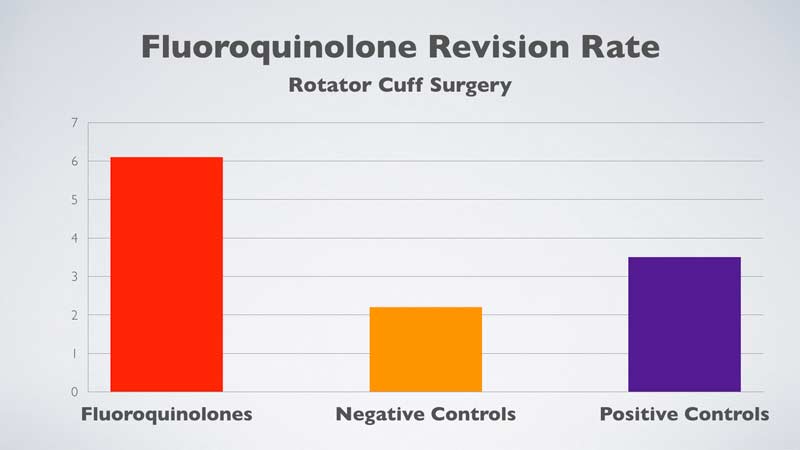

Recently, a published study investigated the effect of the use of fluoroquinolones in patients following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair of the shoulder.14 A total of 1,292 patients were prescribed fluoroquinolones within six months postoperative arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, and they were compared to 5,225 matched negative controls and 1,597 matched positive controls. The fluoroquinolones were prescribed to the 1,292 patients as follows:

- 442 patients within 2 months post-surgery.

- 433 patients within 2–4 months post-surgery.

- 417 patients within 4–6 months post-surgery.

The subsequent revision rate of rotator cuff surgery was found to be significantly higher in the patients prescribed fluoroquinolones within two months of surgery (6.1%) when compared to matched negative (2.2%) and positive controls (2.4%) (figure 1). There were no significant differences in the rate of revision arthroscopic rotator cuff repair when fluoroquinolones were prescribed to the patient at greater than two months post-surgery. The authors concluded that, “Early use of fluoroquinolones following rotator cuff repair was independently associated with significant increased rates of failure requiring revision rotator cuff repair.”

Precautions in the Performance Enhancement Training and Rehabilitation of the Athlete Presenting with Illness

If the athlete has been prescribed a fluoroquinolone class of antibiotic for their present or past illness while participating in a performance enhancement training program for their sport of participation or during rehabilitation for a particular injury or pathology, there are apparent concerns that arise under these circumstances.

During the performance enhancement training of athletes, high levels of exercise intensity are to be avoided during weight room activity, plyometric training, and sprinting velocities. High-intensity and high-impact exercise performance correlates to high levels of tendon stress. Exercise execution also results in a tendon response, as the loading of tendons during vigorous athletic enhancement training and sport participation has been cited as the principal pathologic stimulus for tendinopathy1. Special precautions are to be taken under these specific fluoroquinolone medication conditions to avoid the possible inducement of tendinopathy and perhaps even tendon rupture.

My anecdotal experiences have demonstrated that it doesn’t require relatively high levels of stress to induce a tendon injury when prescribed fluoroquinolones. Share on XMy anecdotal experiences have demonstrated that it does not require relatively high levels of stress to induce a tendon injury when prescribed fluoroquinolones. For example, one of my professional peers had completed a prescribed dosage of ciprofloxacin for an upper respiratory infection. Shortly after completing his medication, he was in the weight room performing the bench press exercise and, unfortunately, ruptured his pectoralis major tendon with a barbell weight of 185 pounds. He certainly didn’t perceive this barbell weight as high intensity, because the weight was programmed as a “warm-up” set intensity. However, this applied stress was undoubtedly ample enough to result in a tendon rupture.

Over the years, I have also rehabilitated recreational and competitive athletes diagnosed with fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy who, although they were cautioned to avoid aggressive exercise and/or physical activities, did so on their own accord and eventually experienced an Achilles tendon rupture.

Physical Rehabilitation for Tendinopathy

At the time of the acknowledgement (diagnosis) of the athlete’s tendinopathy, it is likely that physical rehabilitation will be recommended. There are rehabilitation professionals who approach the treatment of tendinopathy with an emphasis on eccentric exercise application. These rehabilitation treatment regimes in which the tendon is subjected to sustained physiologic load are popular in addressing tendinopathy15, as eccentric exercise performance has been reported to be 90% successful in active individuals or sport participation athletes with tendinopathy16, as well as the documented successful management of tendinopathy with the application of heavy loads17. Loading a tendon with eccentric exercise and/or heavy load may be appropriate for the treatment of tendinopathy, but it is not likely suitable for the care of those individuals with the distinct condition of fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy.

Loading a tendon with eccentric exercise and/or heavy load is likely not suitable for the care of athletes with the distinct condition of fluoroquinolone-induced tendinopathy. Share on XTake Precautions When Prescribed Fluoroquinolones

The performance enhancement training of athletes, as well as the rehabilitation of various pathologies, often requires the appropriate application of aggressive high-intensity exercise execution. These applied intensities will not only stress a tendon, but they require a significant tendon response that is often reactive in nature upon the ground surface area. Athletes who present with illness or a history of illness should be medically assessed, including a review of all prescribed medications. The prescribing of fluoroquinolones may present the athlete with the risk of tendinopathy, as well as possible tendon rupture.

Special consideration and precautions should be taken during the application of the performance enhancement training and rehabilitation program design at the time of the prescribed fluoroquinolones and up to six months from the time of the athlete’s completion of the medication. When an athlete presents with winter illness, a discussion about possible alternative antibiotics excluded from the fluoroquinolone classification of medications is recommended.

References

1. Manfulli, N., Sharma, P., and Luscombe, K.L. “Achilles tendinopathy: aetiology and management.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2004; 97(10):472–476.

2. Garrick, J.G. and Requa, R.K. “The epidemiology of foot and ankle injuries in sport.” Clinical Sports Medicine. 1988; 7(1):29–36.

3. Yang, J., Hodax, J.D., Machan, J.T., et al. “Factors Affecting Return to Play After Primary Achilles Tendon Tear: A Cohort of NFL Players.” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019; 7(3):1–8.

4. Mai, H.T., Alvarez, A.P., Freshman, R.D., et al. “The NFL Orthopaedic Surgery Outcomes Database (NO-SOD): The Effect of Common Orthopaedic Procedures on Football Careers.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016; 44(9):2255–2262.

5. Möller, A., Astron, M., and Westlin, N. “Increasing incidence of Achilles tendon rupture.” Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1996; 67(5):479–481.

6. Schepsis, A.A., Jones, H., and Haas, A.L. “Achilles tendon disorders in athletes.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2002; 30(2):287–305.

7. Kujala, U.M., Sarna, S., and Kaprio, J. “Cumulative incidence of Achilles tendon rupture and tendinopathy in male former elite athletes.” Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005; 15(3):133–135.

8. Oliphant, C.M. and Green, G.M. “Quinolones: a comprehensive review.” American Family Physician. 2002; 65(3):455–464.

9. Bailey, R.R., Kirk, J.A., and Peddie, B.A. “Norfloxacin-induced rheumatoid disease.” The New Zealand Medical Journal. 1983; 96(736):590.

10. Lewis, T.G. “A rare case of ciprofloxacin-induced bilateral rupture of the Achilles tendon.” BMJ Case Reports. 2009;2009 doi:10.1136/bcr.08.2008.0697.

11. Khaliq, Y. and Zhanel, G.G. “Fluoroquinolone-associated tendinopathy: a critical review of the literature.” Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003; 36(11):1404–1410.

12. Akali, A.U. and Niranjan, N.S. “Management of bilateral Achilles tendon rupture associated with ciprofloxacin: a review and case presentation.” Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery. 2008; 61(7):830–834.

13. Chajed, P.N., Plit, M.L., Hopkins, P.M., Malouf, M.A., and Glanville, A.R. “Achilles tendon disease in lung transplant recipients: association with ciprofloxacin.” European Respiratory Journal. 2002; 19(3):469–471.

14. Cancienne, J.M., Brockmeier, S.F., Rodeo, S.A., Young, C., and Werner, B.C. “Early postoperative fluoroquinolone use is associated with an increased revision rate after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 2017; 25(7): 2189–2195.

15. Khan, K.M. and Cook, J.L. “Overuse Tendon Injuries: Where Does the Pain Come From?” Sports Medicine and Arthroscopic Review. 2000; 8(1):17–31.

16. Fahstrom, M., Jonsson, P., Lorentzon, R., and Alfredson, H. “Chronic Achilles tendon pain treated with eccentric calf-muscle training.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2003; 11(5):327–333.

17. Beyer, R., Kongsgaard, M., Hougs Kjær, B., et al. “Heavy Slow Resistance Versus Eccentric Training as Treatment for Achilles Tendinopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” American Journal of Sports Medicine.2015; 43(7):1704–1711.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF