Should there be different approaches to rehabilitation for elite athletes, weekend warriors, adolescents, and sedentary individuals?

At the most basic level, objective data is gathered and combined with subjective reporting and then tested against a hypothesis. This process is repeated again and again until hopefully something changes—at which point the process continues, but the intervention changes. Through this application of the scientific method, which has worked over and over and over in both medicine and science, high-level college and professional athletes around the world get back on the court, pitch, or any field of play.

Why, then, are the steps we take to rehabilitate non-elite athletes different?

There are a host of reasons I’ve seen reported by patients and clinicians as to why this method isn’t used and, subsequently, progress in rehab is not attained. Over the course of the last 15 years, I have worked in private practice with youth and recreational adult athletes, the geriatric population with a variety of diagnoses, and higher-level athletes who were specifically rehabbing to return to sport. Most recently, I have spent my time at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, where I have focused on the treatment of the hip and lower extremity in an active population that includes everyone from recreational adults to professional athletes at the highest levels.

Due to constraints of insurance, patients traveling nationally or internationally to come to HSS, season demands, and coordination with care teams, I can have anywhere from one to 12 sessions over 3-4 months to evaluate and treat these patients. Regardless of who comes in or how long they will be with us, it is critical to gather information that we will use to evaluate and treat them as efficiently as possible.

Addressing Challenges to the Rehab Process for Non-Elite Athletes

Time, money, insurance coverage, motivation, staff availability, and facility limitations all present challenges for the practitioner. These are all valid, but are they insurmountable? Let’s break a few of these down further.

1. Time

The time allotted for a follow-up session of physical therapy in an in-network setting is somewhere in the ballpark of 10-30 minutes of 1:1 care. In that time, the therapist must:

- Get a subjective assessment.

- Test objective measures.

- Assess what, if any, alterations to the plan of care need to be made.

Of course, the overall length of the session is longer, but the amount of undivided attention available after the initial 10-30 minutes is minimal; hopefully, the patient has been put on a path to success and can execute the goals of the session. In an out-of-network or cash-based clinic, the amount of time spent 1:1 is likely higher, but the formulation of the plan must come somewhere in the beginning of that session and needs to be efficient to make sure time—the most precious commodity of all—is not wasted.

2. Money

This is not too different from time, and here again the number of immediately available tools for the treatment of the non-elite athlete may not be as broad as one would like. Access to the combination of force plate testing data, Biodex® isokinetic testing, power testing, and dynamometry (or a similar battery of instruments) is often financially out of reach.

3. Insurance Coverage

This may need the least amount of explanation, but requesting authorization, submitting reauthorization, peer-to-peer calls, and letters of medical necessity all stand in the way of what clinicians actually want to do—which is deliver a high level of care to their patients and get them better.

4. Motivation

This is where things get interesting. Patients are typically very motivated to get better at the start of their care: how could they not be? They can’t do the thing they love, want, or need to do.

However, once they begin to improve and their function increases just enough to accomplish some of their responsibilities in life, rehab becomes a bit less of a priority both in and out of the clinic. It becomes incumbent upon the clinician to find ways to keep patients engaged and moving in the right direction, which takes a toll and often leads to diminishing results and patients falling off the schedule.

The ability to have specific numbers for the percentage of deficit when speaking to coaches, MDs, and insurance companies has proven to be very valuable. Share on XClearly, patients truly do want to get better, and clinicians truly do want to help them, but questions remain:

- Why do daily performance and rehabilitation and progress notes lack objective measures that can help guide the care of these patients and help further the case for insurance coverage beyond the initial six sessions that insurance companies (and sometimes patients themselves) think they need?

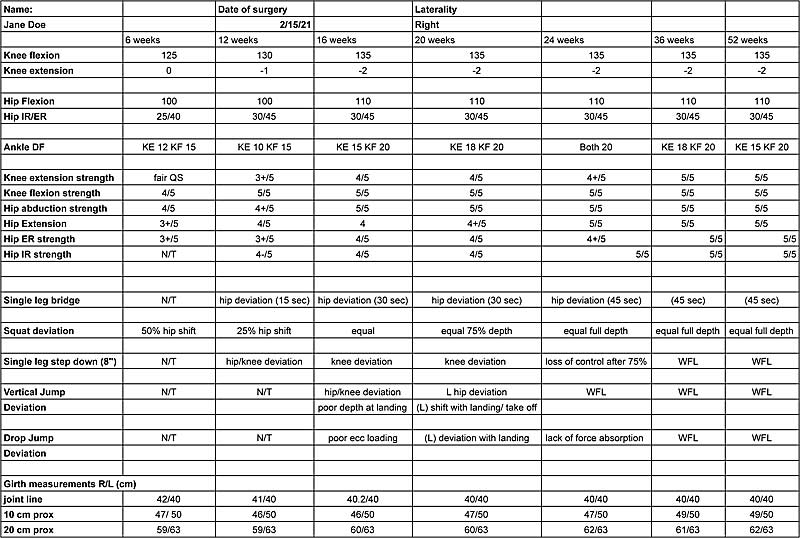

- Why is objective data for returning to sport taken sporadically and usually measured later in the rehab protocol without comparable data?

- Why do clinic owners invest in cumbersome, non-integrated measurement tools that are difficult to implement during the course of a follow-up session and may not give the specific data clinicians are looking for?

- Why does the interpretation and presentation of this data to clients, MDs, and insurance companies often look like an Excel spreadsheet rather than the kind of colorful and easy-to-follow PDF we can get from a kiosk at a drugstore when choosing orthotics?

Finding Tools That Combine Performance and Rehabilitation

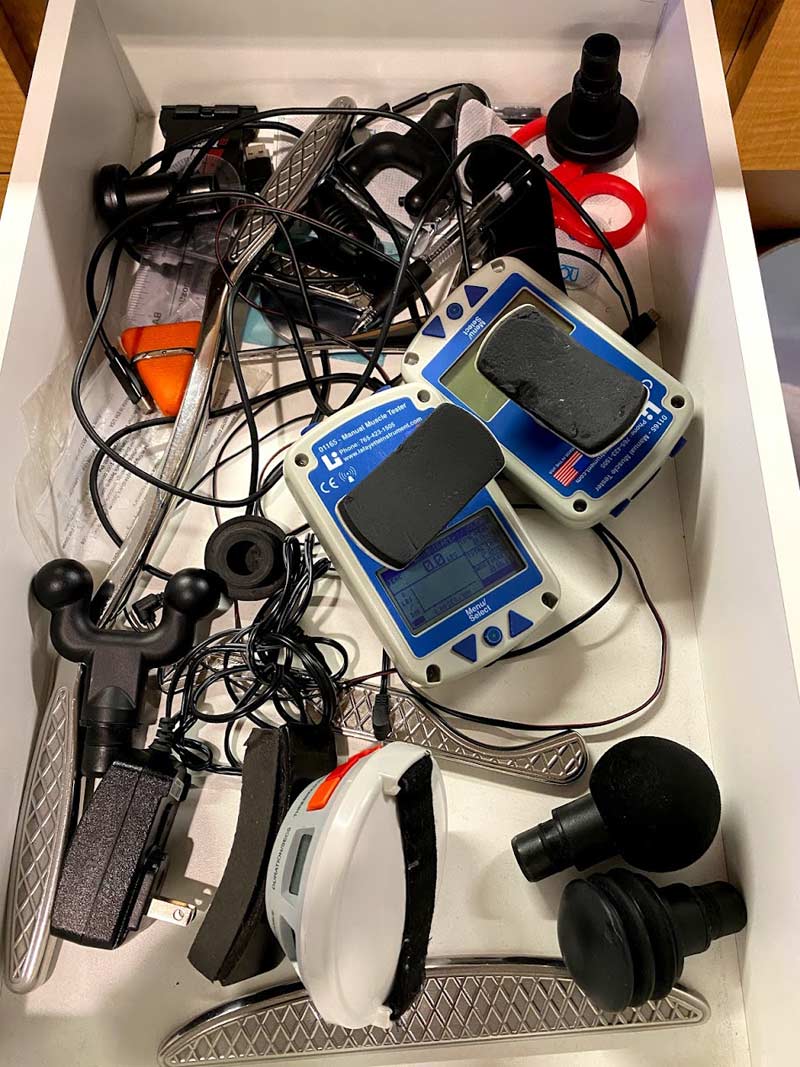

For many years, I had these frustrations, and I have used many hardware and software solutions with varying degrees of success. Products like the MicroFET®, Lafayette Hand-Held Dynamometer, and Biodex® are all reliable and valid and have stood the test of time. In my practice and in the practice of the clinicians around me, however, it’s very difficult to get user adoption due to time, training, data collection, and delivery. This leads to most of this equipment being bought and then lying in a drawer or taking up a corner of a clinic without being used regularly.

That said, Biodex isokinetic testing is unmatched in its ability to measure specific metrics, and it continues to be used for both practical and research purposes.1 However, for the purpose of systematically testing patients as a part of their follow-up sessions, it is a bit too time-consuming—not to mention that unless you are a part of a research or teaching institution, the likelihood that one is available to you is low.

Over the last decade, there has been a significant increase in the crossover between performance and rehabilitation products, and companies like VALD Performance have come out with suites of outstanding products to measure strength, acceleration, and power. One major downside is the cost of both hardware and software. Another, which is more clinical, is that the standardization of strength testing with the force frame also limits the positions available to test and does not provide an option to test pull strength—rather, it opts for push dynamometers.

I have used these devices, and as I said, they are all very capable in their own right, and some are even the gold standard. However, in the context of a 10- to 30-minute session—or in the timeframe of testing and re-testing within a longer session—they are limited. The final and maybe most unique limitation is that all this hardware is used overwhelmingly for testing or measuring. It is limited in its ability to apply this data to engage and train the patient/client, making it a bit one-dimensional.

Through a fair amount of trial and lots of error I was able to find Kinvent, a French company that delivers on a very good idea: create a more efficient and effective way for clinicians to measure and implement objective data, then pair it with an easy-to-use iOS and Android app.

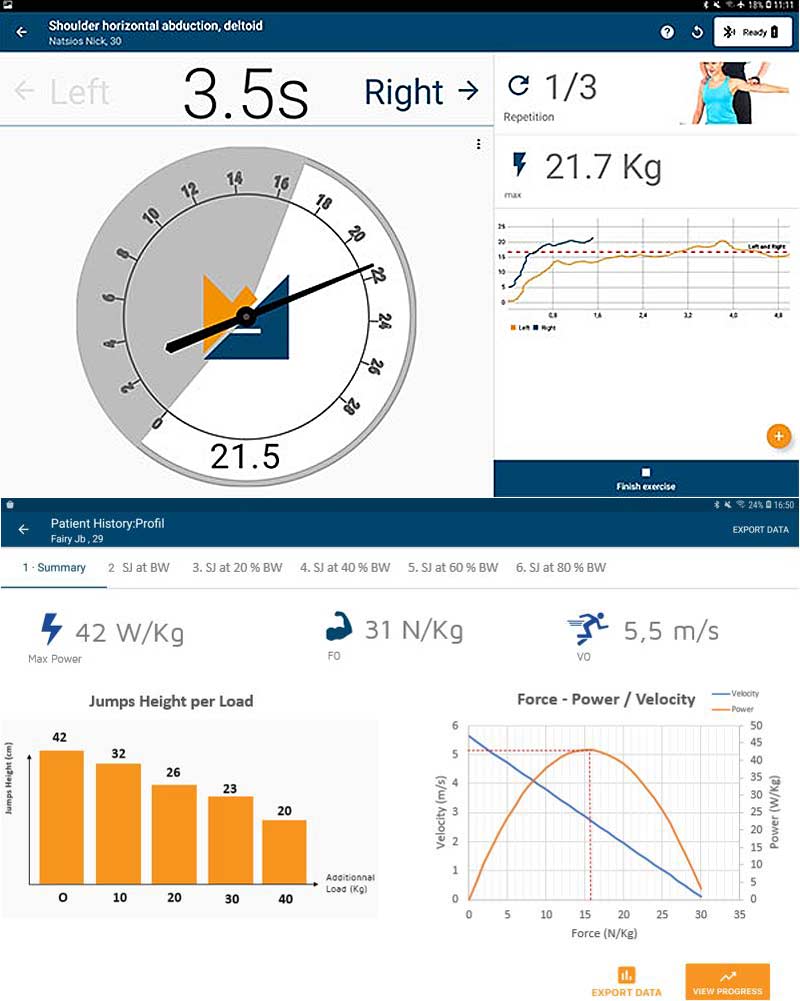

Kinvent has designed biofeedback games into the app so that clients and clinicians are able to use the data they have collected to exercise and develop the given body part or movement. Share on XHaving used non-connected, handheld dynamometers before, I was very happy to see max force, averages, rate of force development (RFD), and eccentric load all in real time on Kinvent. Once the app is opened, you can choose to activate a device in “quick” dashboard mode to simply take a measurement without linking to a patient, or you can link a test or combination of tests to a particular patient to track their progress.

Audio and video cues for starting and stopping help the clinician and patient/client progress through the testing, and a report is generated as soon as you’re finished. The other appealing feature is that you are limited only by your creativity in applying the devices. Utilizing the pull dynamometer, Link, you can measure isometric quad strength in patients with anterior knee pain and patella femoral dysfunction, as well as following surgical knee intervention. This has been found to be a key predictor of pain and function.2 Similarly, the pull or push dynamometers can be used to measure shoulder external rotation strength when treating non-operative and postoperative shoulder pain (again, a key factor in improving shoulder function and mechanics).3-6

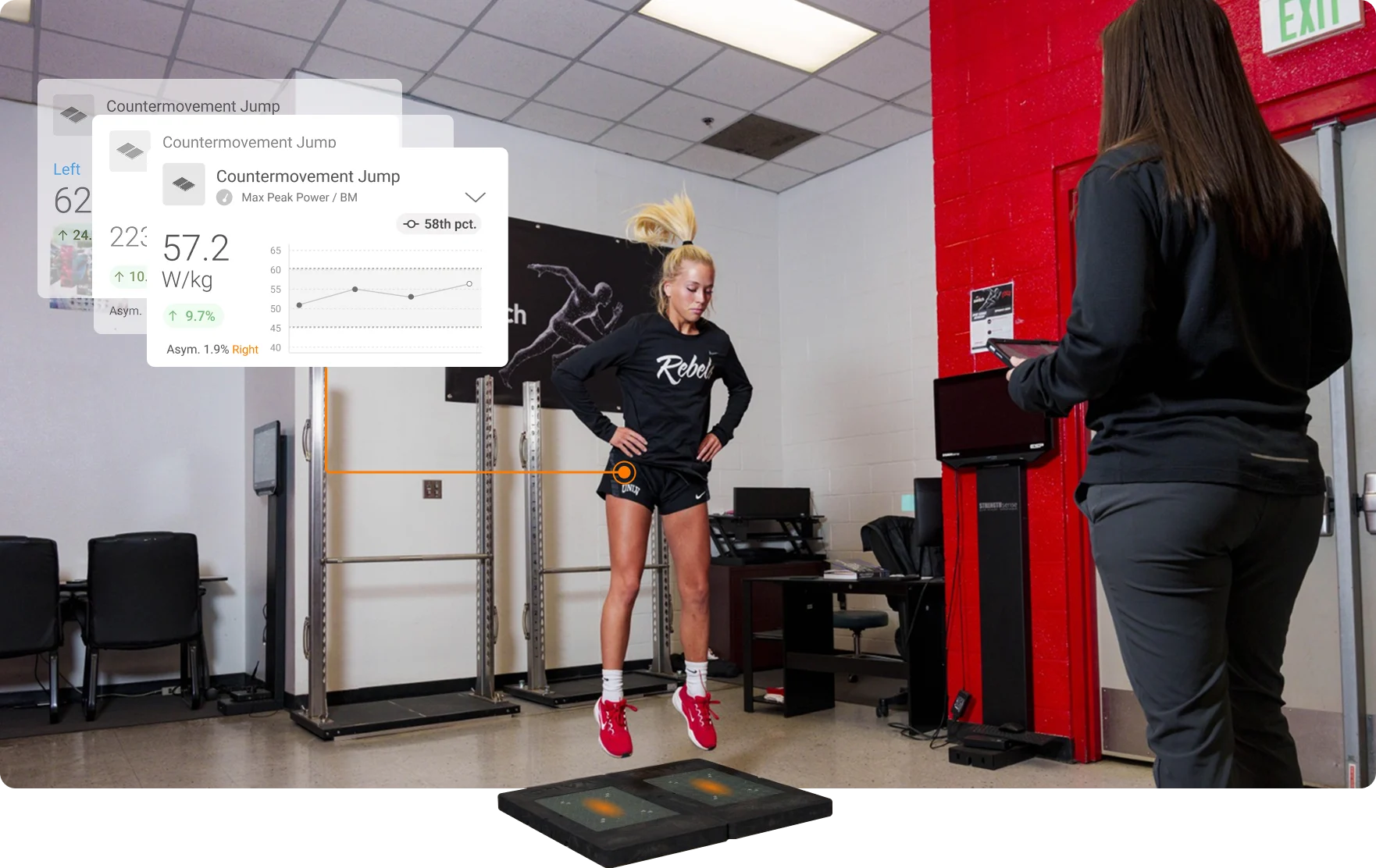

As we return patients and clients to standing dynamic exercise and function, it is critical that they are able to distribute weight evenly and produce both concentric and eccentric force without deviation and pain. The utilization of force plates to assess this has been established in the literature7, and Kinvent’s solution with the “Plates” and the “Delta” allows you to test a wide range of movements quickly and effectively, including squatting, countermovement jump (CMJ), drop jump, single leg hopping, and so on. Further, the push dynamometers can be paired to assess more complex parameters like eccentric hamstring strength using a Nordic testing protocol, which has been shown to assess the risk for injury.8Finally, the force plates can be used to assess upper body stability and power using the push-up test9 as well as the ASH test for shoulder stability10.

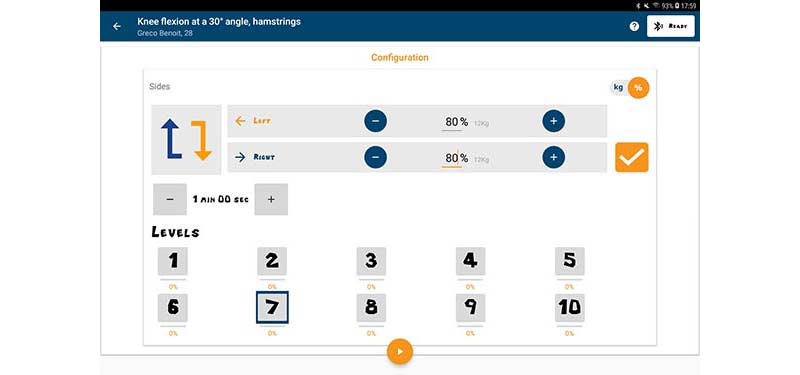

If that were all Kinvent offered, it would be a very well-rounded suite of integrated hardware and software. Kinvent takes things one step further, however. They have designed biofeedback games into the app so that clients and clinicians are able to use the data they have collected to exercise and develop the given body part or movement. Based on the clinician’s reasoning, they can customize the exercise for the most appropriate amount of load for the patient or client, creating a safer and more effective exercise prescription. The result is a highly efficient and effective testing and treatment protocol.

Having used these Kinvent tools for about a year, I have noticed several things about the technology. First, it is not an alternative to taking a good history and gathering subjective and objective measures through interview, special tests, and measures. It is, however, a much more streamlined way of gathering objective strength, motion, balance, and power data during a session. By no means is it the only piece of equipment I use to assess, but the ability to have specific numbers for the percentage of deficit when speaking to coaches, MDs, and insurance companies has proven to be very valuable.

The Kinvent suite is a much more streamlined way of gathering objective strength, motion, balance, and power data during a session. Share on XThe buy-in from patients has also changed. Patients are now easily able to access their own medical record, and athletes look at how they compare to themselves and others as they train.

It’s become more important than ever to track progress and keep everyone on the same page. It is not just what we’re doing, but why we’re doing it. The objective data that backs up the why is critical to success. There has always been and will continue to be some resistance to the addition of more technology into the patient experience, but when the technology allows a clinician to evaluate and treat the patient more efficiently and effectively, it’s worth trying.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

References

1. Zawadzki J, Bober T, and Siemieński A. “Validity analysis of the Biodex System 3 dynamometer under static and isokinetic conditions.” Acta of Bioengineering and Biomechanics. 2010;12(4):25-32. PMID: 21361253.

2. Palmieri-Smith RM and Lepley LK. “Quadriceps Strength Asymmetry After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Alters Knee Joint Biomechanics and Functional Performance at Time of Return to Activity.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;43(7):1662-1669. doi:10.1177/0363546515578252

3. Wilk KE, Andrews JR, Arrigo CA, et al. “The strength characteristics of internal and external rotator muscles in professional baseball pitchers.” American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1993;21:61-66.

4. Reinold MM, Escamilla RF, and Wilk KE. “Current concepts in the scientific and clinical rationale behind exercises for glenohumeral and scapulothoracic musculature.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2009;39:105-117.

5. Clarsen B, Bahr R, Andersson SH, et al. “Reduced glenohumeral rotation, external rotation weakness and scapular dyskinesis are risk factors for shoulder injuries among elite male handball players: a prospective cohort study.” British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2014;48:1327-1333.

6. Uga D, Nakazawa R, and Sakamoto M. “Strength and muscle activity of shoulder external rotation of subjects with and without scapular dyskinesis.” The Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2016;28(4):1100-1105. doi:10.1589/jpts.28.1100

7. Lake J, Mundy P, Comfort P, McMahon JJ, Suchomel TJ, and Carden P. “Concurrent Validity of a Portable Force Plate Using Vertical Jump Force-Time Characteristics.” Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 2018 Oct 1;34(5):410-413. doi: 10.1123/jab.2017-0371. Epub 2018 Oct 11. PMID: 29809100.

8. Wiesinger HP, Gressenbauer C, Kösters A, Scharinger M, and Müller E. “Device and method matter: A critical evaluation of eccentric hamstring muscle strength assessments.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2020;30(2):217-226. doi:10.1111/sms.13569

9. Hashim A, Ariffin A, Hashim T, and Yusof AB. “Reliability and Validity of the 90º Push-Ups Test Protocol.” International Journal of Scientific Research and Management. 2018;6(06). 10.18535/ijsrm/v6i6.pe01.

10. Ashworth B, Hogben P, Singh N, et al. “The Athletic Shoulder (ASH) test: reliability of a novel upper body isometric strength test in elite rugby players.” BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 2018;4:e000365. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000365.