[mashshare]

It seems nothing is more polarizing among coaches than acceleration ladders. In track and field, however, acceleration ladder training and the wicket drill with speed hurdles are trending in popularity. Like medicine ball training, very little research exists on the efficacy of the drills or exercises performed with this equipment. Most advocates of this training concentrate on how to do the drills, not how they work.

What are Acceleration Ladders and Speed Hurdles?

Acceleration ladders and speed hurdles are visually marked paths of foot contact zones or small barriers arranged to encourage specific step patterns. The routines use markings of various forms to space step patterns linearly or to constrain motions performed laterally or in a combination of directions.

An acceleration ladder resembles a rope ladder, usually about one imperial foot square per step zone. Acceleration zones where stride length increases per step often use a ladder device or markings, typically tape or permanent options like paint.

Speed hurdles are usually banana hurdles spaced at distances about the length of a sprinter’s stride. Sometimes other visual markers are used.

Great information about this speed equipment is available here on SimpliFaster, and Mario Gomez and Matt Gifford outlined the use of wicket drills and acceleration ladders in detail. What we haven’t covered yet is the use of acceleration ladders as footwork drills in team sport.

Acceleration Ladders and Team Sports

Very little science or coaching rationale exists with acceleration ladders. For the most part, they’re used to encourage rapid and consistent step patterns. Countless routines exist, and plenty of videos are on the market for coaches who want to help athletes move quicker or to assist athletes develop general coordination.

Most acceleration ladder proponents do not claim that the devices actually help athletes improve their ability to decelerate; the forces placed into each step zone are nothing more than glorified tap dancing. These ladders have been around for decades and simply are another form of tire runs and rope obstacle courses for the feet.

Many proponents consider the exercises to be a higher form of hopscotch. Although playground games like hopscotch are likely great for children, they are inappropriate for sport development—most strength coaches are concerned about eccentric forces, not quick movements.

Acceleration ladder drills, in theory, help prepare an athlete to be elusive with quick movements. Share on XI’ve seen two cases where acceleration ladder drills are beneficial. They help warm-up the body safely and organize groups well. They also help with quick movements to prepare an athlete to be elusive, a part of agility that is often undeveloped. Elusiveness is usually given to the sport coach to instruct, or it’s accepted as part of the athlete’s creative process in youth sport.

As games and competition increase, opportunities either will improve for learning self-organization or retard development from lack of event exposure. Even today, the world’s best athletes are constantly performing agility or footwork exercises in various forms, and it’s hard to say the drills accomplish anything other than general coordination awareness.

How Do Acceleration Ladders and Speed Hurdles Theoretically Work?

- Acceleration ladders improve the efficiency of early acceleration by spacing each step to create the correct rhythm, modeled after successful athletes.

- Speed hurdles, known better as the wicket drill, are designed to improve stride technique at top speed.

Some elite athletes have trained with both approaches while others have succeeded without glancing at them. My point is that these exercises are just options and are not essential to reaching elite status. And even if one doesn’t use the exercise routines and equipment does not mean one can’t learn from the concepts behind them.

Acceleration Ladders

Acceleration ladders are not new. I first read about them in the 1990s in a Remi Korchemny article in a Track and Field News article collection manual. While I like the concept, the questions and problems raised by the method are fair and true.

Is the exercise a visual marker for the coach to reinforce mechanics or for the athlete to be held accountable? Does the challenge of the step pattern encourage explosive action while practicing patience? Does the drill provide a way to encourage ideal shank angles during contact and reduce overstriding?

Currently we don’t know if the exercise intrinsically accomplishes any of these or if it enables the coach to assist in teaching these elements. I will answer these questions later in the article and offer some ways to evaluate the transfer of the drills and training.

Speed Hurdles

The wicket drill with speed hurdles has some key benefits, in theory; it teaches a rhythm pattern, helping with front-side mechanics, and improves foot strike power. The approach used, rather than the medium, helps athletes progress.

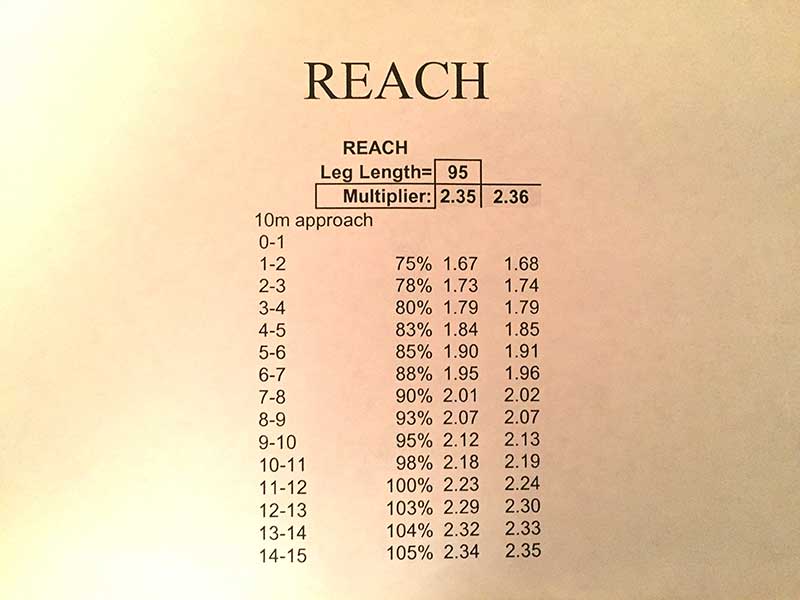

Digging deeper, we find that the goal of the wicket drill is to keep athletes aware of maintaining their stride length while they run, usually at submaximal speeds. It’s only possible to keep stride length consistent if the athlete runs slower than maximal velocity; at top speed, fatigue shortens stride length due to a drop in power.

The wicket drill is used to keep athletes aware of maintaining their stride length while they run. Share on XThe goal of wickets, therefore, is to establish a controlled speed that encourages a clean landing stride with the athlete’s conscious involvement. The rationale for using the drill is to keep the pelvis up and straight, as well as ensuring the athlete doesn’t over-stride or rush the steps from dropping the knee during recovery.

Theoretically, a better submaximal stride will increase the output of force when an athlete increases their effort and intent. It’s commonly believed that some specificity transfers to competitive periods, and it’s up to science to discover the reasons why. Like any track drill, the value is only as high as the skill of the coaches providing the instructions. Motor learning is very complex, and a single exercise isn’t a magic bullet, but some training methods are more likely to be successful than others.

I first saw the wicket drill twenty years ago when Gary Winckler presented information at the USATF schools. At the time, he was using line markers, not mini hurdles. Vince Anderson greatly increased the adoption of this exercise and, with his disciples, expanded the use of marked step pattern runs beyond passing through “checked” stride zones. Andreas Behm and other coaches have helped spread the use of the exercise, which even prompted articles on how to build mini hurdles.

The Science of Acceleration Ladders and Speed Hurdles

I haven’t discovered a body of research or a large number of studies examining acceleration ladders or speed hurdles. During an extensive search, I found information about acceleration ladders and exercises with similar equipment mentioned in studies, but not a set of studies proving whether or not they’re effective. Perhaps the name of acceleration ladders and speed hurdles created confusion in the search, but so far I’ve found nothing of interest.

Reader Note: If you find something, please include a link in the comment section below.

Evaluating the efficacy of acceleration ladder and speed hurdle activities is difficult to do, as kinetic and kinematic data isn’t easy to create without a lot of manual analysis and monkey work. Still, the questions remain: What do you measure during these drills, and how do they carry over to maximal performance?

When the goal for linear sprinting is horizontal speed from point A to point B, force production is useful but doesn’t require a force plate to measure. Agility measurement is much harder, but we can measure simple change of direction abilities, such as the classic 5-10-5 drill in combine testing.

We can evaluate acceleration changes with 0-10m timing or similar, along with motion or video analysis for changes in mechanics. So far, no plausible explanation besides empirical evidence has presented itself. It seems the circles of proponents and detractors simply don’t intermingle enough to have these discussions or to share training information to prove their positions.

Based on simple experimentation with wicket drills, we can conclude that acute changes to foot strike are clearly evident in the videos. Good cueing and spacing encourage an athlete to step-over to land with crisp strides. The velocities are highly dictated by run-up speed, distance between marks, and how much knee lift the coach is expecting.

Acute changes to foot strike are clearly evident with wicket drills. Share on XMost wicket runs are 20-30m with various approach distances and run-off lengths. This means athletes are likely to produce 10-15 solid strides of quality movement.

I’ve looked at videos and calculated velocities. Most of the speeds are under 10 m/s, but some athletes who have aggressive acceleration with sufficient length have gone faster than 10 m/s while maintaining great recovery mechanics. This may be helpful later if the athlete achieves faster race times due to changes in technique.

There is not much research on, or coaching experimentation with, ladders, hurdles, and other stride and step marking routines. Because most of the proponents of these drills argue they are technique tools, changes in speed and kinetic form is likely beyond an 8-week intervention for elite athletes. Novice athletes will probably improve from anything sane tossed at them.

Direct changes of power, acutely, don’t happen with any of the drills. In fact, the force plate analysis we did with the drills and the routines mentioned above showed no interesting changes in the force-time curve that could theoretically be evidence of neuromuscular adaptations.

With isokinetic testing of hip flexor power, we did see small but significant changes in the hip at higher velocities, but nothing maximal strength-wise. One fine change was EMG activity of the anterior shin during recovery, but the differences in peaks and averages were inconsistent to see a pattern.

Acceleration Ladder and Speed Hurdle Workouts: Evaluating Progress

For the record, I am not an expert in these activities and have never owned an acceleration ladder. I used one during my short stint as an intern with the Tampa Bay Rays, and I only observed catchers working on quick response (likely for a wild pitch scenario).

I’ve used side markers and, at times, a piece of tape to help track changes with acceleration and sprint hurdles. I don’t use acceleration markers with team sport athletes often, only if a problem lingers longer than I think is normal.

If we don’t time events, athletes may not truly change their mechanics; speed is sometimes necessary for transfer to sport form. This is why embedded timing, where data’s collected without distracting from the task of execution, is key.

There’s also a problem with rhythm. While a steady beat is ideal, fatigue always interferes with a perfect tempo. Many runs that employ stride patterns are set to a rhythm that isn’t sustainable unless it’s submaximal.

Many runs using stride patterns are set to unsustainable rhythms. Share on XIn sprint races, one wants to “die gracefully,” but losing speed means the stride parameters are likely changing rhythm with a slow leak of power. I’m not suggesting that athletes rehearse slowing down. It’s just interesting to see and discuss how fatigue and managing decay in specific rhythms are part of the wicket drill and similar exercises.

We should also evaluate plyometrics and other specific exercises to see if they transfer to increased displacement lengths of a wicket run. We may see changes like an increase in speed or an increase of the length of spacing.

When running submaximally, as with hurdles, an athlete can only increase frequency when stride parameters are constrained. So athletes may increase the speed of each rep with the same step and contact length, indicating improvement.

Specific posterior chain exercises along with stiffness work at the ankle and knee might be related to the proficiency of the wicket runs, making the exercise a great test in itself.

Wicket runs also train a skill set very appropriate for hurdlers, who need to focus on shuffling and other specific skills to improve their speed between hurdles.

Wicket runs help hurdlers train shuffling and other skills to improve speed between hurdles. Share on XFinally, I suggest implementing a performance therapy program and general pillar development system to maintain both critical mobility and pelvic positions at a pulse rate of 5 per second. Much of Dr. McGill’s work on bracing (stiffness) occurs at a frequency that is too slow or a force level that isn’t demanding enough.

- The goal is to have a systemic strength program. The function of the foot all the way to the hip is enough to leverage the athlete’s ability without making them dependent on daily treatments.

- Any measurement that shows a cause and effect relationship is a good metric in my book. It doesn’t need to be exhaustive or fancy. It just needs to do the job.

- Recognize the difference between stride length and contact length to understand how technique becomes refined over a career. Using only stride length can be a solid reference point because the drill discourages overstriding or excessive casting of the foot.

- Use what works for you and always video from a perpendicular angle midway through the run to see improvement of kinematics or sprinting movement—the core reason for using the drill.

A Balanced Perspective on Using Acceleration Ladders and Speed Hurdles

Except for using acceleration ladders as part of a warm-up, only one choice exists with acceleration ladders and speed hurdles—either you use them, or you don’t. Due to the time required to master anything, doing only a few sessions of drills will not magically fix errors or cause progression. While dramatic improvement is possible with sprinting neophytes, long-term development can’t happen in the short term.

Coaches have to invest ample time in the training to reap benefits down the road. Coaches can choose to use all three approaches religiously, avoid all three like the plague, or do something in the middle.

Speaking for myself, I do have my athletes work on a few departure steps to teach displacement and temporal awareness with block starts, only because they can replicate near actual outputs. No true rules exist with step marking, just ideas that may or may not work with your program and athletes.

A healthy approach is to revisit the promises attributed to acceleration ladders and speed hurdles and see if alternatives exist that may be just as effective or even better. Is equipment necessary to change technique? Are errors in stride mechanics just growing pains of sprinting that will slowly fade away over time? Do programs improve from simply reducing an athlete’s wear and tear by choosing a less demanding session? There are many questions that must be answered by the coach. I use what I feel works for me.

Sometimes great cues and great drills are not repeatable in everyone’s program. A transfusion of benefits may not occur all the time. Some successful programs are only effective in their entirety and using pieces from them won’t create the same changes.

Coaches have to decide if these exercises are worth their time and energy. Also, an athlete’s dedication to their craft dictates their improvement. Ladders for acceleration and wicket runs need set-up time and careful expansion of length, all investments with the potential to be executed haphazardly.

Are Acceleration Ladders and Speed Hurdles Right for You?

At this point, it’s hard to give specific suggestions or protocols. I will say that experimentation requires advance planning. If you believe any of these methods and equipment can help your program, by all means try them and evaluate how the sessions connect to game outcomes and race results.

I haven’t used an acceleration ladder in years, so I don’t know how they may have affected the team sport athletes who have worked with me. I mostly use acceleration points for video and looking at positive shin angles. And I’ve only tried a few maximal velocity runs using banana hurdles a few times.

Don’t feel pressured to try something or to avoid it. Nearly every coach fights the internal draw to be part of a community or coaching school. Being a bit of a maverick isn’t easy, but the goal of training is to help athletes achieve their goals, not be part of a tribe.

If you find traction and wish to adjust your routines with equipment or instruction, and it works, keep doing it, and share with others. If you don’t find value in them or you struggle to implement them in your environment, don’t lose sleep. Plenty of options exist.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]