[mashshare]

As a coach, I am probably like most of you reading this article. I do not have a master’s degree or a doctorate, and I do not have years of research under my belt. What I do have are 22 seasons of coaching experience, the hundreds of speeches I have listened to, and the thousands of pages of articles I have read. All three have helped shape my ever-evolving coaching philosophy.

Like most high school track-and-field coaches, my team at Lake Forest High School (IL) does not have access to an indoor track. We spend most of our time before spring break in a gym, a hallway, the wrestling room, or the weight room. We adapt and persevere out of necessity.

Part of our recent sprint success at Lake Forest can be attributed to the fact that we get a lot of great multi-sport athletes out for our program. Our three themes for a successful pre-season and early-season sprinting program—Acceleration, Coordination, and Variation—are another huge factor. Everything done in the general and specific preparation phases of the season revolves around those three themes.

Acceleration

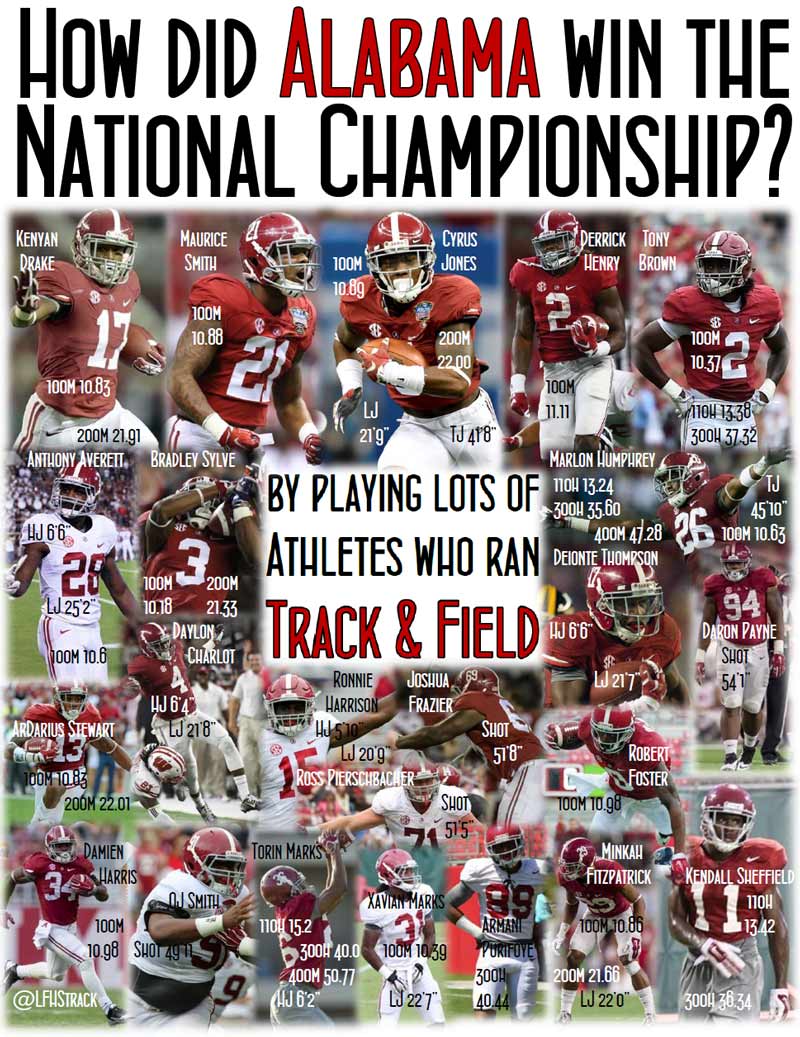

Acceleration is an essential element for nearly every event in track and field, and almost every sport in the world. Football is often described as a game of inches. People get to those inches by accelerating to them. Acceleration wins games and races. Part of the reason football, basketball, and soccer players make such great track-and-field athletes is because they already have a lot of experience with acceleration. Perhaps the greatest enticement we can make for multi-sport athletes to come out for track and field is that we will teach them proper acceleration.

Acceleration should be taught on day one and should still be a focus the last week of the season. The importance of acceleration in sprinting events can hardly be overstated. The ability to accelerate to top speed appropriately will not only help the athlete get ahead early in the race, but will also help them achieve a higher top speed. But not all acceleration starts out of the blocks. Relay members, jumpers, and pole vaulters also need to learn proper acceleration in order to succeed in their events.

When teaching acceleration, progression of position is more important than progression of distance (1). Progressing from a 10m start to a 20m start to a 30m start is very logical. But progressing from a two-point start to a three-point start to a four-point start to a block start will help you get the best out of your athletes. The two-point start is the most logical place to begin, as it closely mimics the start of acceleration in other sports (2). Regardless of fitness level or experience, all athletes should begin with the two-point start. Some coaches introduce block starts on day one. However, until an athlete is able to properly accelerate without a block, they should not be given the much more complex task of starting with a block.

There are dozens of ways to practice acceleration (falling starts, push-up starts, kneeling starts, etc.) and dozens of other drills to help with acceleration (wicket drills, acceleration ladders (3), stair hops, etc.). There have also been hundreds of articles written about the proper start mechanics, but all that research can only be applied after systematic work on acceleration. Most athletes naturally want to sprint too soon, and start their acceleration by moving their head. This initial action causes them to stand up right away, display frontside mechanics too early, and curb their acceleration (4). Consistent and repeated exposure to proper acceleration work can fix crucial mistakes such as these.

Consistency of acceleration can win meets as well. However, that consistency does not come to athletes who have coaches with lackadaisical approaches to acceleration development. The long jump, triple jump, high jump, pole vault, and javelin athletes with consistent coordination will hit their marks more often. Hurdlers have to hit that first hurdle in stride or risk having their entire race compromised. Consistency in the handoffs is a goal of every 4x100m relay team. Athletes who have weeks and month of practice in acceleration will be more consistent as the outgoing runner, which is a huge deal in a race where 0.05 seconds often determines the difference between winning and not winning, qualifying and not qualifying, and scoring and not scoring.

Acceleration is the suggested first macrocycle in a short-to-long program. Even when the focus shifts to power, top speed, speed endurance, or any other theme, acceleration remains a priority. Every block start, hill repeat, interval, handoff, run-through, and approach will help the athletes hone their acceleration in a specific environment. The base for all this work is built in the first part of the season.

Athletes with poor acceleration lose races, while athletes with effective acceleration win them. Share on XSimply put, athletes with poor acceleration lose races. Athletes with effective acceleration make winning look easy.

Coordination

The emphasis placed on coordination was perhaps the most confusing aspect of all of the coaching journals I read and the presentations I watched as a young coach. Every top coach I studied, from Boo Schexnayder to Loren Seagrave to Tony Veney, seemed to talk quite a bit about how important coordination was to sprinters and phosphate athletes. How could this be?

Does it take great coordination to run in a straight line? Yes, it does! Running at top speed is an exceptionally coordinated skill. Almost everybody can see how running the 4x100m relay or the hurdle events can take incredible coordination, but the coordination needed for the general sprinting events is often overlooked (5). Have you ever seen a robot run on two feet? Nope. Running at top speed is basically a repeated process of falling and catching yourself several times a second. It is an extremely complex, coordinated task.

Multi-sport athletes have great success in track and field due partly to superior coordination. Share on XPart of the reason multi-sport athletes have such great success in track and field is because of their superior coordination. Football players, traditionally, make the best track-and-field athletes because of their combination of speed, strength, power, explosion, and mindset. But do not discount their amazing coordination as well. The most coordinated events in track and field are the hurdles, and there is a long list of great football players who were also outstanding hurdlers (Bo Jackson, Roger Craig, Willie Gault, Rod Woodson, Tyrone Wheatley, Qadry Ismail, Ted Ginn Jr., Jamaal Charles, Robert Griffin III, Jabari Greer, Brian Hartline, Todd Gurley, Ezekiel Elliott, Devon Allen, etc.). Basketball, soccer, volleyball, field hockey, lacrosse, wrestling, baseball, handball, and tennis athletes also have incredible coordination.

Virtually everything done in track-and-field practice will have some coordination element to it, and the more you can match the activity to the event, the better. Sprinting at top speed is in itself a great coordination exercise. You can also add coordination to your practice plan during the warm-up, speed drills, plyometrics, body weight circuits, and lifting routines. Most sprint programs have basically melded their warm-up and speed drills together. The days of jogging followed by static stretching are long gone. Skipping, backwards running, bounding, galloping, and various other locomotor activities are great at developing general and specific coordination, but only if done while closely mimicking proper running form. Such drills also contribute to flexibility and elasticity while also getting the athletes ready for the demands of a track-and-field practice.

Dynamic stretching activities such as walking lunges, side lunges, knee grabs, flamingoes, speed skaters, and the like deal with balance, which is an aspect of coordination. However, they are not as applicable to sprinting coordination due to the fact that the athletes are never airborne. Adding an element of balance to weightlifting, such as having the athletes use a physio ball instead of a bench for bench press, can have great proprioceptive benefits. However, these should also be considered a buttress to your coordination activities, instead of a pillar.

The previous section of this article was about acceleration, and this section is very much about deceleration. Every athlete will decelerate at the end of a race. Much of that deceleration is due to poor race modeling and energy system failure (6). But deceleration is just as often caused by lack of coordination due to central nervous system (CNS) fatigue (7).

Coordination exercises build up the CNS, in essence giving your body a bigger “battery.” A long sprint will erode even the most fit athlete’s CNS. Those with superior coordination will be able to keep themselves upright and headed toward the finish line because they are able to maintain the proper posture. You will notice athletes falling apart and losing coordination more in their second, third, and fourth events of a meet because their CNS is fried. They may have the energy to get to the finish line, but their eroded coordination makes the journey more difficult.

The erosion of coordination is also present at practice, which is why the tasks that require the most coordination should take place immediately after a proper arousal warm-up (8). Starts, acceleration, top speed work, handoffs, fast hurdle work, intense intervals, run-throughs, plyometrics, and the like should come first. More stationary activities, like hurdle mobility, body weight circuits, medicine balls, balancing routines, and weightlifting should take place near the end of the practice session.

Be patient and involved when working on coordination, because the neuromuscular system takes time to develop. Building the pathways to improved recruitment, force production, and coordination is not an overnight task. Extremely gifted athletes can master new tasks relatively quickly, while we mere mortals will need guidance, patience, and repetition. That is why coaching and monitoring athletes during all their activities is so important. There is a point and purpose to every drill and every skill. Some athletes just go through the motions but, as a coach, you must ensure they are active in putting their foot to the ground, instead of letting gravity do the work (9). Results are maximized when adequate time and care are taken to develop appropriate coordination.

Variation

Athletes need to learn movement patterns common to their sport, but they also need variety to avoid overworking their muscles, tendons, and ligaments. Planned variances should be employed throughout the course of the training program. Variety enhances adaptation by increasing the complexity of the training stimulus. This forces the body to adapt in different ways, making it inherently better at adaptation (5). A good variety of skills, drills, and exercises can help your athletes become strong, healthy, and competitive.

There are many ways to apply the variation principle to your early-season practices. You can start implementing this principle right away with your warm-up and speed drills. As mentioned earlier, the days of jogging followed by static stretching are long gone. The lack of variety is one huge reason for this. Instead, those skips, bounds, and drills that aid your athletes with coordination are also adding necessary variety.

Performing a variety of drills can be great, but varying the way you do each drill can be beneficial as well. We do not learn by constantly repeating the same solution to a movement problem, but by constantly solving new movement problems (11). Rather than just having the athletes do bounds, you could set out cones and have the athletes aim to land next to each cone on the bounds. These cones can then be lengthened, shortened, or mixed-up to add variety. The distances and heights can be varied for mini-hurdles and box jumps. The athletes will see it as a challenge as well, since it’s different from most maximum effort challenges inherent in sport.

The central nervous system is basically a computer programmed by repetition (10). But the CNS also needs variation to assess all the possibilities of movement in between known skills. Repetition is great for rhythm and learning, but jumping the same way every time can lead to overuse injuries and micro-trauma (11).

One of my favorite track videos, below, is not of a race or a competition. It is of a drill, and the commentary is not even in English.

Video 1: Stefan Holm Hurdles Training

The video shows Stefan Holm, the 2004 Olympic Gold medalist in the high jump, who holds a personal best of 7’10.5” despite standing only 5’11”. The spring in his legs is impressive, of course. Also note that he is training for the high jump without actually high jumping. The next video shows how he adds variety to his training by “high jumping” six different ways. The variety keeps him jumping while decreasing the risk of overuse injuries.

Video 2: Six Degrees of Jumping – Stefan Holm

He still has to work on approaching the mat correctly and negotiating his body over the bar, but he is giving his muscles some variety and therefore reducing his chances of an overuse injury. Of course, this is a man who had been a world-class high jumper for a decade before the video was made. High school jumpers will need time to develop the muscle memory and rhythm of the event. But variety can be a great way to keep your athletes healthy, hoppy, and happy.

For instance, having the entire team do hurdle drills can help them with their hip strength and mobility. It can also help the coaching staff discover which athletes may be naturals at hurdling. We have days in the first few weeks of practice when each athlete rotates between four stations: high jump, long/triple jump, pole vault, and hurdles. The event coaches get a chance to discover which athletes have talent in their discipline, and the athletes get some exposure to a variety of different training activities. The time at each event station is short—around 20 minutes. After a few weeks, the time is increased, but the choice of stations is decreased. Athletes have to specialize eventually, but giving them exposure to new events helps with talent identification and variation of training.

Variation can be applied to your weight-room sessions as well. For our first two lifting cycles, we give the athletes a choice on most exercises to use the machine, the bar, or the free weights. The main benefit is that, with up to 60-70 sprinters and jumpers lifting, the increased options will lead to less standing around. Another benefit is that the athletes come from different weightlifting backgrounds and may be more comfortable with one type of lifting over another. We specialize our lifts later in the season, but early on the variety helps us in numerous ways.

As your season progresses, limit the athletes to the drills and skills that best aid in their systematic retrieval of information. If every week is a new series of gimmicks and drills, the level of skill acquisition is greatly diminished (7). Be wary, however, of taking too much out of your program. Insufficient diversity in exercise choices, especially later in the season, can create declines in flexibility and elasticity (8).

Where Is the Endurance?

Some of you may be looking at these themes and wondering how we get our athletes in shape. First off, I would like to say that “in shape” is a generally meaningless phrase. Being “in shape” can mean 100 different things. People too often confuse good cardiovascular endurance for being “in shape.” If a football player and a cross-country runner both try out for the basketball team, odds are the football player—though his cardiovascular endurance will almost certainly be lower—will be in better shape for the basketball season. The cross-country athlete will surely be in better shape for long, sustained bouts of exercise, but the football player will be used to the stop-start motion, cutting, jumping, and constant acceleration and deceleration of basketball.

The phrase ‘in shape’ is generally misused. ‘In shape’ is not having good cardiovascular endurance. Share on XCoordination and variation can be two great themes, even for distance runners (12). The best distance runners I have ever had the pleasure of coaching were all great athletes.

Back in 2003, I was as an assistant cross country coach at Eau Claire Memorial High School (WI) under head coach Mark Johnson, whom everybody called “Mojo.” The skips, bounds, hops, sprints, hurdle drills, and dynamic stretches of Mojo’s warm-up looked straight out of a sprinting practice.

Our best guy was Ryan Loshaw, who was a school record holder, city champ, and conference champ, and placed 15th at the state championships. He was also an All-State swimmer on the sprint relays, and now does professional CrossFit competitions. (He has put on around 40 pounds of muscle since high school.) Our best girl was a freshman named Katie Bethke, who was the school record holder, city champ, conference champ, and sectional champ, and placed seventh at the state championships. She started for the varsity basketball team all four years, was All-State in soccer three years, and played professional soccer for five years after graduating from a record-breaking soccer career at the University of Minnesota.

Billy Bund, the best distance runner I have coached at Lake Forest, played football and baseball his freshman year of high school. He didn’t run a step until his sophomore year, and ended up in the Top Five at state championships in cross country and the 1600m run.

Distance runners need endurance work, of course, but they can also benefit from the coordination and variation aspects described here. Speed workouts can also have a dramatic effect on distance runners (13). IMG Academy coach Loren Seagrave points out that a main difference between national class and world-class distance runners is not necessarily their resting heart rate or VO2 max: It’s their 20m fly time (9). Speed kills, no matter what the distance.

Sprinting and jumping build speed. Endurance does not build speed. A great pre-season and early-season program that focuses on themes of acceleration, coordination, and variation can help your sprinters, hurdlers, and jumpers achieve their end-of-season goals.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF

[mashshare]

References

- Sanders, Gabe. “Acceleration Progression – Working from the Top Down.”

- Gifford, Matt. “Developing a Contest-Specific Acceleration Model.”

- Gifford, Matt. “The Acceleration Ladder.”

- Seagrave, Loren. “New Neuro-Biomechanics of the Start & Acceleration.” February 6, 2016. WISTCA Clinic, Madison, WI.

- USATF Coaching Education Programs – Level 2 Sprint/Hurdles/Relays

- Thomas, Latif. “3 Reasons Sprinters Fall Apart at the End of Races.”

- Veney, Tony. “The Complete Guide to Track & Field Conditioning: Sprints & Hurdles.”

- Schexnayder, Boo. “The Complete Guide to Track & Field Conditioning: Jumps.”

- Seagrave, Loren. “New Neuro-Biomechanics of Max Velocity Sprinting.” February 5, 2016. WISTCA Clinic, Madison, WI.

- Fichter, Dan. “Train the Nervous System.” June 18, 2016. Track-Football Activation Consortium III, Lombard, IL.

- Smith, Joel. “Plyometrics.” June 18, 2016. Track-Football Activation Consortium III, Lombard, IL.

- Christensen, Scott. “Coordination as a Primary Physical Component in Cross Country Training.”

- Pickering, Craig. “Should Distance Runners Do Speed Workouts?”