The Benefits of Coaching an Effective Warmup (and How to Do It)

By Raymond Tucker

Summary

A well-structured warm-up not only prepares athletes physically but also offers insight into their mental and physical readiness, enhances focus, reinforces quality movement patterns, and reduces injury risk. The warm-up provides coaches the opportunity to teach correct movement patterns to reinforce proper mechanics. This leads to helping athletes increase movement literacy over time, which also helps prevent injuries.

Introduction

Your warm-up may be the most crucial—yet often disregarded—component of your strength and conditioning program. Taking the time to better develop and coach your athletes’ warm-up can transform your strength and conditioning program, ensuring that your athletes are prepared for the next team practice, game, or strength and conditioning workout. Coaching your athletes’ warm-up has several performance benefits.

- Allows you to check the climate of your athletes. How are they feeling? Are they tired, stressed, or sore?

- Improves their mental focus, preparedness, and even increases their confidence level before a workout, practice, or game.

- Reinforces higher quality movement patterns and the body positions required for the upcoming activity, which can reduce the chance of injury.

- Communicates clearly to your athletes that the general warm-up is a serious component of your strength and conditioning program.

Over the years, however, I think coaches have neglected some of the modalities used in a general warm-up, primarily due to research studies conducted in exercise sports science labs. As coaches, we need to remember that some researchers may have never coached on the field, and their conclusions are based on data analysis, not anecdotal evidence. Some researchers might not be looking at the hands on, practical benefits or may not discuss their findings with strength and conditioning coaches, athletic trainers, and athletes.

Over the years, I think coaches have neglected some of the modalities used in a general warm-up, primarily due to research studies conducted in exercise sports science labs, says @DrRaymondTucker. Share on XThis article will go over some of the benefits of coaching a warmup and hopefully provide you, the coach, with some intrinsic motivation to take this part of your training program seriously.

Static Stretching & Dynamic Warm-Ups

There are several different types of stretches that you can do as part of your warm-up:

- Myofascial release techniques.

- Static stretching.

- Active stretching.

- Ballistic stretching.

- Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching.

- A dynamic warm-up.

Static stretching is a highly controversial topic, with mixed results from research on the benefits of its use in improving athletic performance. We have all read or heard other coaches say that static stretching is a waste of time and does not improve speed, vertical jump, or athletic performance…and this could be a true statement if you do static stretching and then sprint, jump, or play in a game.

Static stretching, however, was never intended to be used in that way. When done correctly, the primary purpose of static stretching is to increase flexibility and range of motion (ROM), decrease musculotendinous stiffness, and reduce the risk of acute muscle strain injuries. According to research studies conducted by Riewald, S. (2004)1, the appropriate, recommended duration for static stretching is 15 to 30 second and has been shown to be more effective than shorter durations.2,3

We are quick to throw the baby out with the bath water—according to some of the research, we may not have been performing static stretches correctly. We can all remember the standard command of “touch your toes and count to eight,” which is clearly not holding the stretch for 15-30 seconds. This could be one of the reasons we are not getting the true benefit of static stretching. I heard an Olympic track coach say that for every paper that says static stretching is inadequate, you can find one that says it is beneficial. Gymnasts are some of the best athletes in the world and they use static stretching to increase flexibility, improve range of motion, and reduce the risk of injuries (especially strains and sprains), which are crucial elements for their demanding sport.

Gymnasts are some of the best athletes in the world and they use static stretching to increase flexibility, improve range of motion, and reduce the risk of injuries, especially strains and sprains. Share on XOlympic track and field coach Dan Pfaff states:

“One has to consider that sports science, although of great value, is often disengaged from the day-to-day life of most coaches and athletes. Studies are conducted in laboratory settings and clinical environments. Results can be an aid to performance, but ultimately it is interpretation and application of the findings by coach and athlete that will determine what works and what doesn’t. The dynamic warm-up is here to stay, but in the way computer manufacturers update their software to advanced and hopefully better programmes, perhaps it’s time to review your dynamic warm-up and determine whether you can upgrade it to greater effect. Including controlled, static stretching may bring benefits, after all.”

I strongly agree with Coach Dan Pfaff and think reviewing research studies in strength and conditioning is a good idea. Coaches need to read beyond the abstract and conclusion of a research study, taking time to also to examine:

- How the study was conducted.

- Where it took place.

- Who the subjects were.

I dedicate time to reviewing various research studies, but I also evaluate whether my methods with athletes have improved their performance and reduced injuries. If my approach proves effective, I will continue to implement it.

Choosing Your Warm-Up Movements

As a foundation of the warm-up I use with my athletes, we always start with a myofascial release by foam rolling. After the foam roll, we will transition into an active warm-up followed by a dynamic warm-up. I take the time to coach each part of the warm-up, because each part prepares the athlete for the next part of the warm-up.

By taking the time to coach your dynamic warm-up, you can identify any imbalances, range-of-motion restrictions, or movement problems (i.e., compensating a movement pattern due to an injury), and then make necessary changes to your training plan.

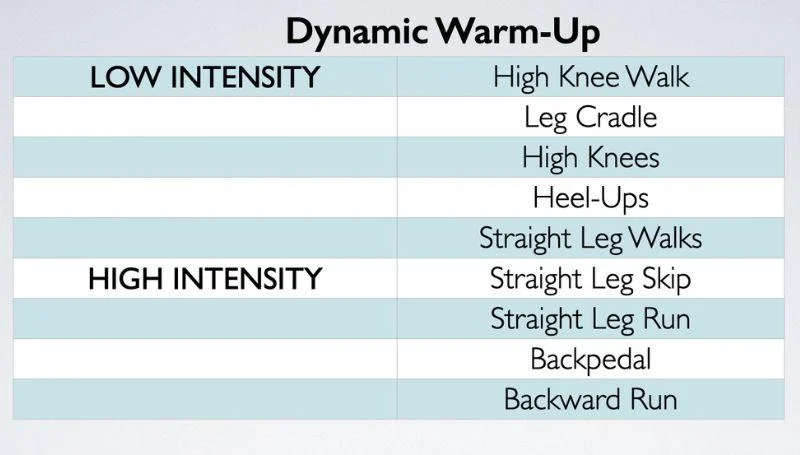

After our active stretching, we transition directly into our dynamic warm-up. This starts with low-intensity, slow, controlled movements to increase their heart rate and blood flow to muscle tissue. As the athletes’ bodies get warmed up, we move into more specific, high-intensity exercises to prepare the athlete’s muscles and joints for the day’s movement patterns. There are various motor skills that you can perform. These are some of the motor skills that I have used in my dynamic warm-up.

By taking the time to coach your dynamic warm-up, you can identify any imbalances, range-of-motion restrictions, or movement problems and then make necessary changes to your training plan. Share on X

Table 1. Dynamic Warmup

Proper Coaching In the Warm-Up

The bottom line is this: whatever stretching or general warm-up you do with your athletes, you need to take the time to coach it. Coaching the warm-up sends a clear message to your athletes that the workout session has started and this is a serious part of the training session.

If the warm-up segment of your workout is not supervised and coached correctly, if you have a team captain leading a stretch, or if you have your athletes stretch on their own…then some of your athletes will not perform the exercises properly. Some will merely act like they are stretching, and in some cases this turns into a horse-play session and a waste of valuable training time. I do not have a captain or team leader lead the stretch, because that doesn’t show your athletes that you take this part of your training seriously—instead, I coach everything from the start of the warm-up to the end of the session.

By taking the time to coach the warm-up, I send a clear message that we will take this part of our training program seriously and need to get mentally prepared and focused for today's workout, says @DrRaymondTucker. Share on XBy taking the time to coach the warm-up, I send a clear message that we will take this part of our training program seriously and need to get mentally prepared and focused for today’s workout. Getting mentally focused does not start when you get under the bar, but it begins at the start of the warm-up.

Video 1. I am looking for the correct body position during the warm-up to perform the proper movement patterns used later in the workout or team sport practice.

I heard Kevin Carr from Michael Boyle Strength and Conditioning (MBSC) on The Athlete’s Edge Podcast state that: “a warm-up is not just a warm-up for younger kids, this is motor skill development. It is teaching them the postures and positions and motor control that we want.”

As coaches, we like to get right into the training session, and this could mean that the warm-up segment is rushed, or we really didn’t get warmed up at all. Then we wonder why we see athletes still trying to stretch out a tight area or complain of being tight during their workout. Another essential benefit of a supervised warm-up is that it increases the athletes’ mental preparation, which improves their confidence and allows them to prepare and focus on the workout, contributing to improved athletic performance.

As coaches, we need to understand the difference between motor skills, motor programs, and motor learning to understand why supervising and coaching a warm-up is genuinely beneficial.

- Motor skills are defined as the body’s ability to perform specific movements using muscles, encompassing both fine and gross motor skills, which are essential for everyday activities.

- Motor programs are defined, pre-structured sets of motor commands stored in the brain that allow for the execution of specific movements or skills, including the sequence, force, and timing of muscle contractions.

- Motor learning is defined as the process by which the brain adapts to control the body, involving changes in the nervous system and structure to acquire and refine motor skills through practice and experience.

When performing a dynamic warm-up, we should teach athletes the proper movement patterns used in various motor skills so that they can reproduce these skills when called upon in a practice or game. When we teach these motor skills, the brain stores them as motor programs that include the kinetic and kinematic properties of those skills. Motor learning is the process by which the brain acquires and refines motor skills through practice and experience.

When performing a dynamic warm-up, we should teach athletes the proper movement patterns used in various motor skills so that they can reproduce these skills when called upon in a practice or game, says @DrRaymondTucker. Share on XWe run into a problem, however, if the motor skills used in the dynamic warm-up are not coached with the correct movement pattern: athletes will repeatedly perform these motor skills with the wrong movement patterns. The brain does not have a filter system to determine which motor skills are done with the correct movement pattern and which ones are wrong, and it will store these motor skills in the brain to be used when called upon.

By not teaching the correct movement patterns in your motor skills during your dynamic warm-up, your athletes will end up reproducing a faulty movement pattern that could potentially lead to an injury or decrease athletic performance. For example, one of the most popular dynamic warm-up exercises is the A-skip. We could, however, be cuing our athletes to land on the balls of their feet in a plantarflexed position with a negative shin ankle that does not produce force when sprinting. This foot position can also lead to ankle injuries. When they are sprinting, however, we are cueing them to apply force into the ground. Consequently, we are teaching one motor skill in the dynamic warm-up and then asking them to perform another when they sprint.

A better approach would be to cue the athlete to get their foot into a dorsiflexed position, with a positive shin angle, and land on the midfoot with the heel slightly off the ground; this will help the athlete understand how it feels to apply force into the ground (RFD), and continue this force for the remainder of the drill to create impulse. When teaching the A-skip, one of my preferred technical cues is that I want my athletes to start in a tall posture (not slouched over). I tell them to focus on:

- A skipping action while bringing the knee up to waist height, with the support leg in a locked-out position (and not bent).

- Bringing the heel up and toes up by keeping the foot in the dorsiflexed position with the arms in an opposite-arm-to-leg action.

One problem with the A-skip exercise is that athletes bring the knee up too high or exaggerate the rhythm of the skip movement pattern, and the foot then lands too far out in front of the body. Several years ago, I would also use “butt kicks,” another common exercise that many coaches and athletes use. Over time, however, I’ve learned that the hamstrings don’t function that way in sprinting. Instead, the heel should come up directly underneath the glutes with a knee-high lift, with the arms in an opposite-arm-to-leg action and the support leg in a locked position (instead of the slight bend that you could be seeing).

Once again, if we are going to teach the correct movement pattern in our dynamic warm-up, then we need to make sure that we are teaching the proper motor skills so the athletes can perform the correct motor skills when called upon in sport.

Next Stages of Development

As strength and conditioning coaches, we will probably not be fortunate enough to coach an athlete for their entire career. Eventually, another coach will take over and coach one of your athletes, potentially encountering faulty movement patterns that you ignored or failed to correct. Now, this coach has to invest valuable time in fixing those movement patterns.

Eventually, another coach will take over and coach one of your athletes, potentially encountering faulty movement patterns that you ignored or failed to correct, says @DrRaymondTucker. Share on XThere’s an important quote from Gray Cook: “Don’t add strength to dysfunction if an athlete can’t do a basic movement skill, and don’t teach them an advanced movement skill until they have mastered the basic movement skills.” Another quote from Gary Cook that sticks in my mind when I work with athletes is “Your brain is too smart to allow you to have full horsepower in a bad body position, it’s called muscle inhibition.”

Your athletes will never have efficient movement patterns unless they have the flexibility to get into those positions. Appropriate instruction and progression during the warm-up can help ensure that they place the connective tissue in the proper positions to apply force, accelerate, decelerate, and execute athlete actions at game speed.

References

- Riewald, S. Stretching the limits of knowledge on stretching. Strength Cond J 26:58-59, 2004.

- Roberts, JM, and Wilson, K. Effect of stretching duration on active and passive range of motion in the lower extremity. Br J Sports Med 33:259-263, 1999.

- Walter, SD, Figoni, SF, Andres, FF, and Brown, E. Training intensity and duration in flexibility. Clin Kinesthesiol 50:40-45, 1996.