Yes, sprinting at max speed is the most common use for timing lasers, but it’s not the only use—not every run with the systems needs to be at 100% effort/speed or in a straight line.

Timing lasers (such as Dashr, Brower, VALD, Swift, etc.) provide an objective, repeatable, and reliable way of measuring speed. Personally, I’ve found a lot of value in programming and coaching with the VALD SmartSpeed timers. With that simple premise of timing from when the athlete crosses through the first laser to when they cross the last one, there are a variety of valuable uses for multiple aspects of speed training.

Sprinting at max speed is the most common use for timing lasers, but it’s not the only use—not every run with the systems needs to be at 100% effort/speed or in a straight line, says @CoachBigToe. Share on XI’m here to highlight a trio of uses for timing lasers that include all aspects of preparing for sport and game speed (not just sprinting):

- Timing any type of run you can imagine.

- Building into top-speed sprinting.

- Return to play.

Timing Any Type of Run You Can Imagine

Going back to the simplicity of timing lasers, measuring how long it takes the athlete to run through the first laser and consequently the second one, anything done in between the lasers is up to you:

- Example: curve running. Determine how big you want the circle’s radius, set up the cones/rope/whatever you want the boundaries to be, and tell your athletes to run fast. They’ll have extra motivation and objective feedback on whether the rep was better or worse than the previous one.

Video 1: Athlete performing a timed curve run of a full circle.

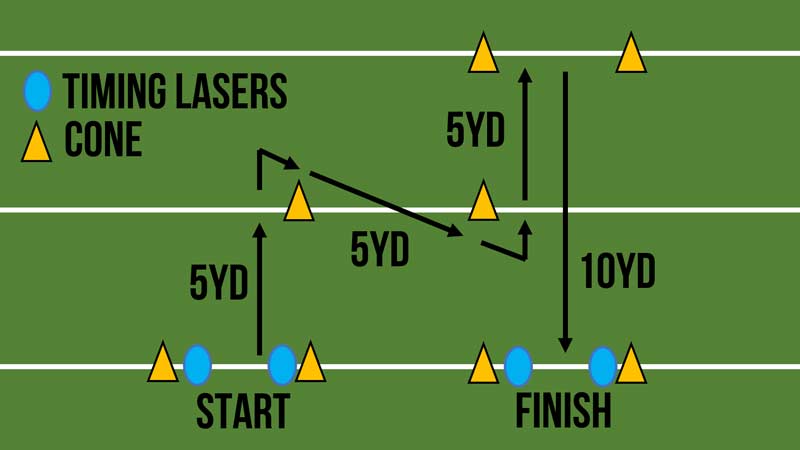

- Example: change of direction test. Besides the standard pro-shuttle/pro-agility/5-10-5 (can we figure out an official name for it, please?), how else do you assess your athlete’s ability to change direction? Below is an example of what you could do if the setup is precise and consistent. Sprint 5 yards, unilateral cut using left foot turning to the right, sprint 5 yards, unilateral cut using right foot turning to the left, sprint 5 yards, bilateral cut touching one foot on the line to turn around, sprint 10 yards through the finish.

Video 2: Athletes performing a 180-degree cut test to assess change of direction bilateral cutting.

- Here’s another example of a change of direction test you can do. The 180-degree cut test uses a simple premise: the athlete crosses the beam to start the time and has to cross it again to stop the time. The athlete starts at the 0-yard line, runs and touches their foot 10 yards away, and runs back, with the laser on the 5-yard line.

Building into Top-Speed Sprinting

Athletes getting back into top-speed sprinting after extended time off can make coaches nervous (not because it’s immediately dangerous, but if done haphazardly, it can be). Using timing lasers can help objectively guide the progression from time off back into max effort sprints.

For example, here’s how you could build up to top-speed sprinting over the course of multiple weeks. Let’s say the athlete’s best fly 10 is 1.00 seconds:

- Session 1: Fly 10s with a 20-yard build-in at 90%, should be around 1.10 seconds.

- Session 2: Fly 10s with a 25-yard build-in at 90%, should be around 1.10 seconds.

- Session 3: Fly 10s with a 25-yard build-in at 95%, should be around 1.05 seconds.

- Session 4: Fly 10s with a 30-yard build-in at 95%, should be around 1.05 seconds.

- Session 5: Fly 10s with a 30-yard build-in at 100%, should be around 1.00 seconds.

If you know an athlete’s best, you can calculate the percentages and give them something to shoot for to drive progress objectively. But coaching with percentages like that can be challenging for some athletes to understand. With the example above, if the athlete is sprinting their fly 10s at a 1.20 pace, will that prepare them for 100% in the following weeks? Probably not.

Is the athlete actually at 90% of their previous best? Is the following session of 95% faster than the previous session at 90%? How else do you know if they’re hitting the speed they’re supposed to hit? Say the athlete’s “90%” is actually 80% speed and you need them to add some speed and intensity. Or, your athlete is excited, comes out at 1.04 when it should be a 1.10, and you need them to dial it back a little. Either way, it’s easier to do so with objective justification and being able to SHOW them their speed. Even if it’s telling them to hit the same speed again, it adds that much more reassurance to the athlete with the numbers to back it up.

Return to Play

Besides progressing through the typical return to play rehabilitation protocols—and eventually regaining the ability to sprint at 100% effort—how else do you evaluate progress? Timing lasers are an effective way to get objective feedback about how an athlete is progressing through rehab. I’ve used objective measurements like this by prompting the athlete “sprint 10 yards as fast as you feel comfortable” and tracking it over time. It might not always be pretty, and it might not be near their best speed pre-injury, but it’s another tool you have to provide even more information about an athlete’s progress.

Timing lasers are an effective way to get objective feedback about how an athlete is progressing through rehab… It’s the most direct way to compare if they’re at 100% of what they used to be. Share on XRehab can be a long, frustrating, and discouraging process. But how impactful would it be to show your athlete that they’re making improvements in the right direction toward their goals, even if those improvements aren’t drastic? How impactful would it be for you to justify calling an audible and modifying your protocols if progress objectively stalls after multiple sessions/weeks? Are athletes done with rehab because they progressed through the exercises or because they can consistently hit the same times as they could pre-injury? It’s the most direct way to compare if they’re at 100% of what they used to be.

Assuming you regularly time sprints in your speed training, you should take “pre-injury” or “baseline” data for your athletes. It’s not the timing lasers themselves but what you do with them and what they help justify that takes your return to play to the next level.

Bonus: Motivation

Not everything that is timed needs to be written down, and sometimes timing lasers can just be used as motivating feedback. You can make up a drill on the spot and instantly draw out more effort just by setting up timing lasers. Make it competitive, make it fun, and watch your athletes run that much faster.

Be creative in new applications of your timing lasers to level up your coaching. This is a different way to think about a tool you might already have to complement what you’re already doing. Whether it’s supporting drawing more effort out of your change of direction drills, helping build back into sprinting more safely, or helping your return to play process and decisions, the only limit is your imagination.

Since you’re here…

…we have a small favor to ask. More people are reading SimpliFaster than ever, and each week we bring you compelling content from coaches, sport scientists, and physiotherapists who are devoted to building better athletes. Please take a moment to share the articles on social media, engage the authors with questions and comments below, and link to articles when appropriate if you have a blog or participate on forums of related topics. — SF