Why More Work Doesn’t Equal Better Results for Athletes

Introduction

A major frustration for strength and conditioning (S&C) professionals is encountering uneducated practices that center around “the way we’ve always done it” despite the way not being rooted in sound training principles. In this article, I discuss this topic and provide evidence-based methods for improving athletic performance. This article can also serve as a “how to” guide for a sport coach who had to assume the role of S&C Coach for their team, but didn’t go to school for it or study for any S&C certifications.

The Misconception of ‘More is Better’

Sometimes, what sets professional coaches apart from hobbyists is not what they do but what they don’t do. A common misconception in coaching is that there is a direct relationship between work and improvement. Tony Holler, creator of the Feed The Cats coaching philosophy, describes the old-school coaches’ mentality, saying they would rather lose than be outworked. We have all had coaches like this. I call this the More Mentality.

Examples of the More Mentality are excessive conditioning – “we have to be in better shape,” emphasizing load over technique in the weight room – “we have to be stronger,” and burning kids out with volume out of blatant ignorance. These are the coaches who blame losses on a lack of conditioning, failing to see that poor performance is likely a result of their methods, which results in fatigued athletes.

There’s no doubt that being a hardworking person is virtuous, but in the context of S&C, doing more work is not the best way to improve athletic performance.

There’s no doubt that being a hardworking person is virtuous, but in the context of S&C, doing more work is not the best way to improve athletic performance, says @PinneyStrength Share on XUnderstanding Athletic Development

To maximize the development of athletes, your practice must be grounded in the science of S&C. Foundational principles of athletic development are individuality, specificity, progressive overload, and recovery.

Individuality Principle:

Individuals respond differently to the same training stimulus. Become aware of your athlete’s unique ability level and train them with an individually appropriate challenge.11 Practically, build progressions and regressions into your program – have three tiers of complexity to accommodate multiple ability levels.

Example:

Level 1 – Push-up bottom position hold

Level 2 – Push-up

Level 3 – Explosive Push-up

Specificity Principle:

The body will adapt specifically to the training demands. The most effective way to improve at any skill is to practice the skill itself.11 Early in my personal training career I worked with a client whose goal was to increase his max number of push-ups, so I decided to focus on the bench press, since it’s the best exercise for building upper body pushing strength. To my surprise, when we tested max push-ups the next month, his performance did not improve. After I got over the embarrassment, we focused on push-ups the next month, doing multiple sets of half his max reps each workout. Miraculously, the next month he doubled his PR.

Progressive Overload Principle:

The challenge of training must gradually and continuously increase to continue improving skill and fitness.11 Periodization is the systematic process of organizing volume, intensity, and exercise selection into structured phases to optimize performance. The following are a few established loading strategies:

Basic Progressive Overload: Adding 5-10 lbs to main lifts each month.6 This simple strategy is perfect for beginner lifters/youth athletes.

- 2-for-2 Rule – Athletes can increase load when they can perform 2 more reps than programmed for 2 consecutive weeks.

Linear Periodization: Starting with high volume and low intensity and shifting to low volume and high intensity throughout the training block.10 This strategy works well with beginner and intermediate lifters.

- Weeks 1-4: 4×8 at 70-80%

- Weeks 5-8: 4×6 at 80-90%

- Weeks 9-12: 4×3 at 90-95%

Block Periodization: Divides training into distinct blocks (2-6 weeks), focusing on improving a specific goal (hypertrophy, strength, power).4 This strategy works great preparing to peak for competition/sport seasons.

- Weeks 1-4: Hypertrophy Block – 5×5 pause reps at 65%

- Weeks 5-8: Strength Block – 5×5 at 80%

- Weeks 9-12: Power Block – 5×3 at 90%

Recovery Principle:

Fitness increases from training are not realized until 1-3 days post-workout when adequate recovery is achieved. Training in the absence of sufficient recovery will cause an accumulation of fatigue, resulting in diminished performance and an increased risk of injury.2

The Role of the Strength and Conditioning Professional

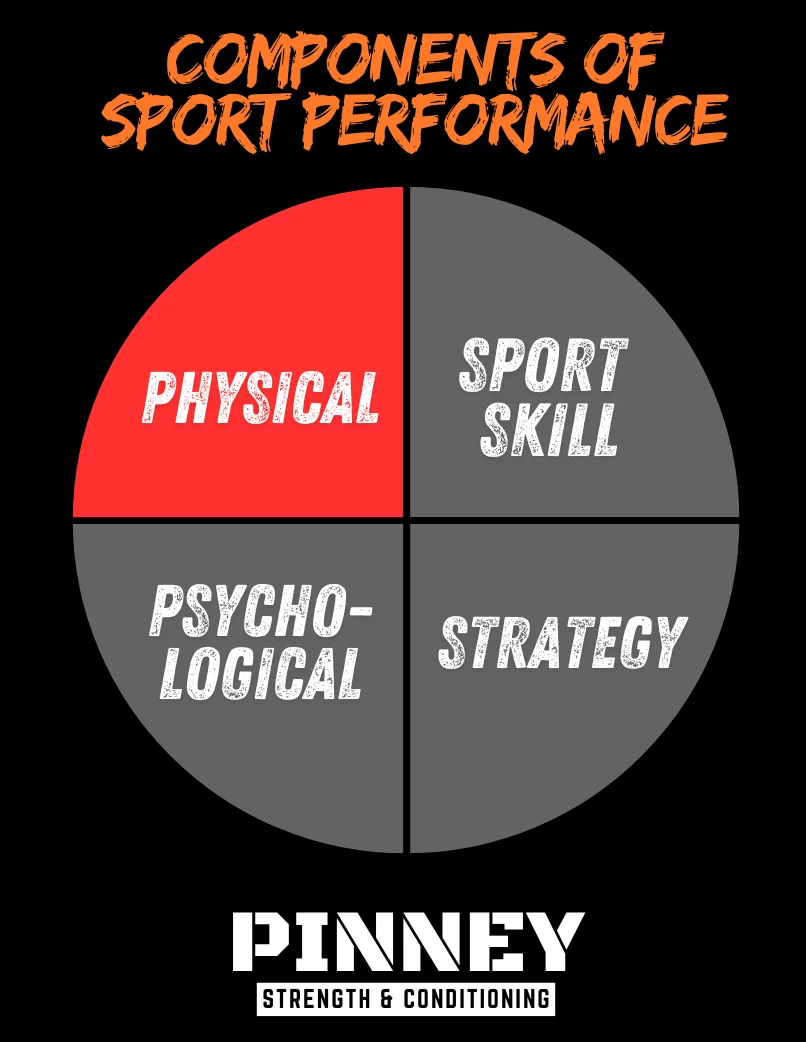

To improve sports performance, we must understand the factors that influence it. I like the four-component model to illustrate the major factors that determine sport performance.

The development of technical skills and game strategy is the responsibility of the sports coach. Athletes forge their mentality as they balance the stress of busy sports schedules, school, social factors, and whatever is happening at home. A strong support system is critical, and coaches can have an impact on athletes’ mentality as well.

The role of S&C coaches is to develop athletes’ physical abilities (agility, coordination, endurance, power, speed, strength). Strength professionals are trained to design and manage evidence-based training programs to enhance sport performance and injury prevention. This includes programming developmentally appropriate exercises, volume, intensity, and rest. S&C coaches teach proper technique, using cues and feedback to facilitate quality movements, and apply progressive overload effectively to enhance adaptations.

Sport coaches commonly assume the responsibility of the strength coach, either by choice or necessity, which can be a big challenge if they haven’t been taught proper principles of training. The purpose of this article is to help those sports coaches take their teams to the next level through the best training practices.

Training Dosage: The Overlooked Variable

Just like medication, training dosage must be precise. Hormesis is a biological term that relates to dosage – depending on the dosage, a stressor can be either beneficial or harmful. Coaches must understand the magnitude of stress placed on athletes during training and the recovery timeline to elicit desired adaptations.

The Fitness-Fatigue Paradigm is a concept in S&C that explains every training session creates two effects – fitness and fatigue. Essentially, following a training session fatigue increases and fitness decreases due to the physical stress. Recovery will occur over the next 1-3 days, leading to increased fitness beyond the original level (supercompensation).2

Recovery time is based on the intensity of exercise. High-intensity training (e.g., maximal lifting, sprinting, jumping) can take as long as four days or more to recover from, especially when high intensity and volume are combined. Not allowing adequate recovery leads to an accumulation of fatigue, resulting in decreased performance and increased risk of injury. This is the situation many coaches get their athletes into, then blame poor performance on a lack of conditioning (don’t do that!). The goal is to stack quality training sessions and adequate recovery repeatedly to enhance performance.

There are several factors that can affect the recovery process, including stress from school, social factors, multi-sport schedules, home life, sleep quality, and nutrition. Coaches should not program for optimal conditions, but realistic ones. If we look at an athlete’s work capacity as a glass of water, all stress (psychological and physical) causes water to be emptied from the glass to varying degrees. Emptying the glass today, by training too hard, will impact the quality of subsequent training for multiple days. The point is that athletes have a finite amount of energy. Coaches should not assume complete recovery or that athletes’ glasses are full and do everything in their power to balance the stress-recovery relationship well.

A common scenario is coaches exhausting their teams with conditioning. Excessive conditioning that lacks appropriate programming kills athletes’ motivation, speed, power, and recovery. It also diminishes the quality of practice. Russian scientist, Yuri Verkhoshansky, who was a pioneer in developing plyometric training for athletic performance, talks about this, saying conditioning before training or practice is a “recipe for disaster,” and the effects of conditioning post practice are not as obvious, but still negatively impact the quality of training.13

Excessive conditioning that lacks appropriate programming kills athletes’ motivation, speed, power, and recovery. It also diminishes the quality of practice, says @PinneyStrength Share on XDuring the COVID lockdowns, I was a part of Zoom calls with prominent college and professional strength coaches. Interestingly, a common thread is that they did not condition their athletes in the traditional sense of running but saw the best method for conditioning athletes for competition is playing the sport itself. This highlights the specificity principle and the misunderstanding of the term “conditioning” in S&C. Being truly conditioned is being prepared for the demands of the sport. The most targeted way to prepare for the demands of a sport is to play the sport itself.

As a football coach, the season is long and grueling. I don’t want to beat up my players before the season even begins. Tony Holler has another concept I’ve adopted concerning preseason training: the goal is to enter the season 80% conditioned and 100% healthy. I want my athletes to be energized and explosive for the season, not exhausted and slow. Often, success in sport comes down to attrition. Coaches with a More Mentality unknowingly do their teams a disservice by beating them up before the season even begins. Coaches who manage the stress placed on their athletes are the ones who will be in a position to compete for championships at the end of the season when it counts.

Side Note: If you made it this far, I’m probably preaching to the choir. Share this article on social media to spread the good word!

Often, success in sport comes down to attrition. Coaches with a More Mentality unknowingly do their teams a disservice by beating them up before the season even begins, says @PinneyStrength Share on XPractical Guidelines

So, what should you do? Here are practical training guidelines to enhance your program.

FREQUENCY

Frequency of training must be looked at in three phases: off-season, preseason, and in-season.

INTENSITY

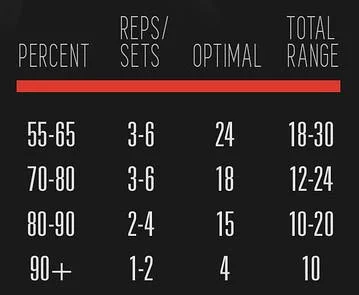

For intensity and volume of training, we look at principles devised in Olympic weightlifting and track and field because these sports produce objective data about what training methods are most effective for increasing physical performance.

Strength/Power Training

Alexander Prilepin was a Soviet National weightlifting coach from 1975 to 1985. He studied the training logs of elite Soviet weightlifters over a decade, which resulted in Prilepin’s Chart, providing guidelines for effective training intensity and volume.5 Of note, comrade Prilepin showed that the average training intensity was between 70-80% 1RM and 90%+ loads were rare and strategic.

Consider that this data was collected from elite weightlifters, so it’s reasonable to suggest that youth athletes can achieve considerable gains in strength and power training at percentages as low as 60%. Jim Wendler, author of the popular 5/3/1 strength program and a former powerlifting athlete under Loui Simmons of Westside Barbell, has developed impressive strength in his high school football players in London, Ohio, using training weights as low as 65%. Prilepin’s research emphasized submaximal intensities done frequently with technical precision, rather than frequent max-effort lifts. This approach builds strength, power, and skill without excessive fatigue.

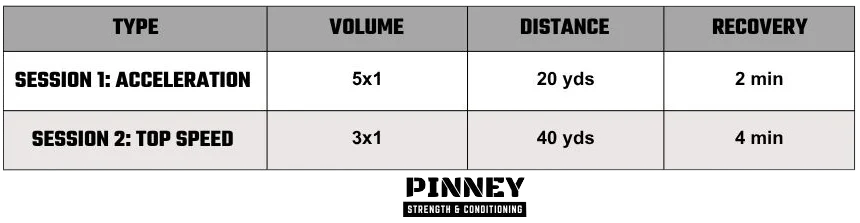

Speed Training

Speed training is a missing component of many youth training programs and is one of the most effective and irreplaceable methods for improving athleticism. Coaches commonly mistake aerobic conditioning for speed work. Speed training is max effort sprinting with full recovery between efforts. Incomplete recovery will result in submaximal sprinting. Simply put, you cannot get faster running submaximally. Sprint training can be divided into acceleration sessions (0-20 yards) and top speed sessions (20-40 yards). Sprint volume should be 2-5 reps, and a good rule of thumb for full recovery between sets is one minute for every 10 yards of sprint distance.

Example Speed Sessions

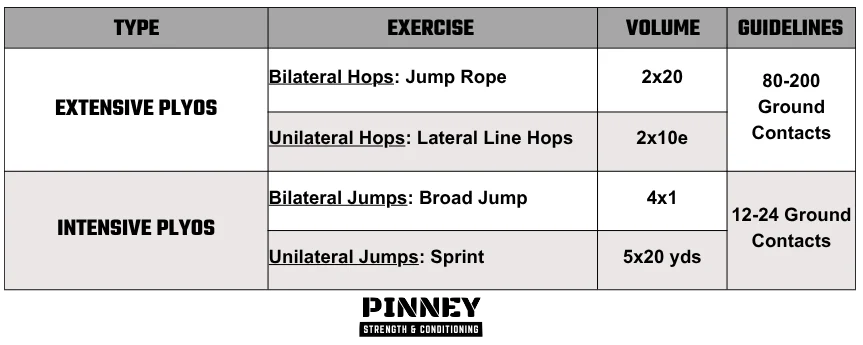

Plyometric Training

Plyometric training develops the abilities to absorb and produce force rapidly, helping weight room strength transfer to explosive athleticism. Plyometrics are characterized by repeated double- or single-leg jumps (sprinting is a form of plyometric). The forces experienced by the body during plyometric exercises are extremely high (5-8x bodyweight as compared to 2-3x bodyweight with traditional strength training). Plyometrics can be divided into two categories: Extensive (low intensity, high volume) and Intensive (high intensity, low volume). Examples of extensive plyometrics are jump rope and line jumps, and intensive examples are broad jumps and weighted vertical jumps.

Example Plyometric Session

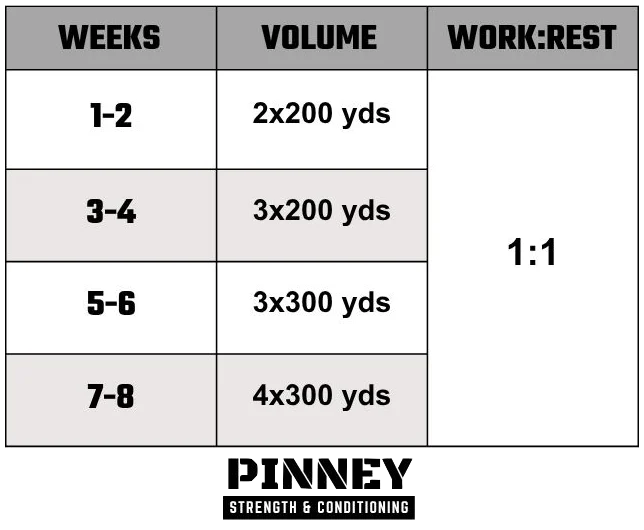

Conditioning

I’ve spent a lot of time chastising the way coaches bastardize conditioning training, but without a doubt there is still value in building an athlete’s aerobic base. Doing so properly will affect how quickly athletes can recover their heart rate between breaks in gameplay. Coaches get it wrong by going too hard from the start. I believe that if you start with a manageable workload and explain to athletes how you are going to progress them and the benefits of aerobic training, you can achieve much better results. The off-season is the time to build an aerobic base by utilizing longer distance/slower running. In the preseason you should begin shifting to the specific work-to-rest ratio of the sport (e.g., football: 6 seconds of intense work: 30 seconds of rest). Finishing practice with a scrimmage period is an effective conditioning method if it is done at game pace.

Periodization

Lastly, when we zoom out and look at the annual plan, it’s essential to consider how training volume is strategically managed to support optimal performance. Going back to the glass of water analogy, as stress from sports increases in the pre-/in-season, it needs to decrease from strength and power work. Just as critical is understanding that athletes should continue to strength train in-season to maintain gains. Don’t be a coach who neglects the weight room in-season. The key here is to cut volume down but keep intensity high to promote explosiveness during the competitive period.

General guidelines from the NSCA recommend that training volume drops by a ⅓ in the pre-season (when you begin practicing) and an additional ⅓ when the season begins.9 I accomplish this by simply dropping a set from all exercises during the preseason and an additional set from the main lift when the season begins (going from 5×5 in the off-season to 3×5 in-season).

Final Thoughts

Don’t be the person whose reason for doing things is because “it’s the way it’s always been done.” There are evidence-based methods that will take care of your athletes and optimize athletic development and sport performance. Implement these methods and dominate your local competition. Let the other guy show up with a dilapidated squad, while you’ve been developing athletes who are powerful, strong, and fast. Conditioned and energized for the demands of the season; prepared to compete when it matters most.

Sources

- Brewer, C. (2008). Strength and Conditioning for Sport: A Practical Guideline for Coaches. Leeds, UK: Coachwise Business Solutions.

- Chiu, L. Z., & Barnes, J. L. (2003). The fitness-fatigue model revisited: Implications for planning short-and long-term training. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 25(6), 42-51.

- Erickson, B. J. (2015). The epidemic of Tommy John surgery: the role of the orthopedic surgeon. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ), 44(1), E36-E37.

- Issurin, V. B. (2010). New horizons for the methodology and physiology of training periodization. Sports medicine, 40, 189-206.

- Kontos, Tim (2021). Utilizing Prilepin’s Chart. Elitefts.

- Kraemer, W. J., & Ratamess, N. A. (2004). Fundamentals of resistance training: progression and exercise prescription. Medicine & science in sports & exercise, 36(4), 674-688.

- Lloyd, R. S., Cronin, J. B., Faigenbaum, A. D., Haff, G. G., Howard, R., Kraemer, W. J., … & Oliver, J. L. (2016). National Strength and Conditioning Association position statement on long-term athletic development. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30(6), 1491-1509.

- Meadors, L. (2016). Practical application for long-term athletic development. National Strength Conditioning Association.

- NSCA-National Strength & Conditioning Association (Ed.). (2021). Essentials of strength training and conditioning. Human kinetics.

- Rhea, M. R., & Alderman, B. L. (2004). A meta-analysis of periodized versus nonperiodized strength and power training programs. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 75(4), 413-422.

- Sands, W. A., Wurth, J. J., & Hewit, J. K. (2012). Basics of strength and conditioning manual. Colorado Springs, CO: National Strength and Conditioning Association, 1, 100-104.

- Understanding The Role Of Rest And Recovery In Weightlifting. USA Weightlifting, 2024.

- Verkhoshansky, Y., & Verkhoshansky, N. (2011). Special strength training: manual for coaches (p. 274). Rome: Verkhoshansky Sstm.

Author Bio

Zach Pinney is a teacher and Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist. He was a President’s Scholar at Cal State Fullerton and is a Marine Corps veteran. Coach Pinney has over 20 years of experience in fitness, including competing in Olympic weightlifting, playing college football, and a decade working as a personal trainer. Currently, he works with hundreds of athletes as a teacher, football and strength coach at the high school level.

Zach Pinney, MS, CSCS

Socials: